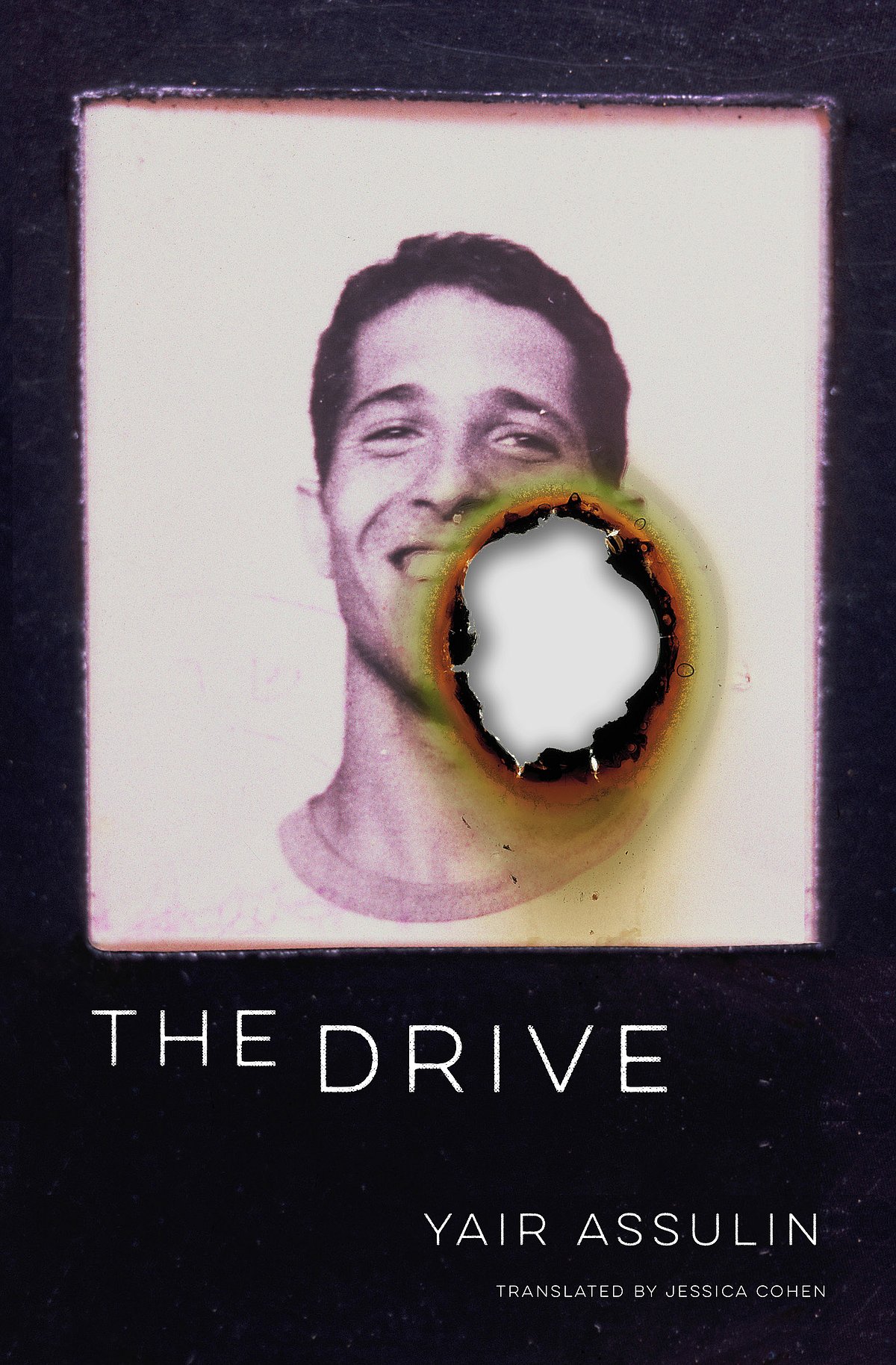

Soldier, at Unease

Of all the jobs in the world, the defence forces are best associated with ideals of honour and sacrifice, patriotism and heroism. However, the narrator in Israeli writer Yair Assulin’s The Drive, conscripted barely out of his teens, has ‘never shared the preoccupation with these things called ‘army’ and ‘values’ or with the dubious glory of ‘defending the homeland’.’ As a young boy, he had imagined magnificence in the army, a great physique, many brave adventures to recount at Friday night dinners, and a confidence, even an arrogance, that he was sure would make him popular with the ladies.

But from his training onward, he progressively gets into a funk that he cannot quite articulate to his superiors or to his worried parents. He thinks he would rather die than have to go back to his base. He is not being abused, neither has he any specific complaint for wanting to leave. If he does leave midway instead of suffering through the years like everyone he knows is wont to do, what would people say? Who would marry him? Who would give him a job? Repeated questions of what he wants to do, what he wants and what he wants to happen from people around him, baffled by his behaviour, are met by the same, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know.’ When speaking with his superiors fails, he and his father set out on a drive to see the Mental Health Officer at Tel Hashomer Hospital.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

This pithy novel, translated from the Hebrew by the Man Booker International Prize-winning translator Jessica Cohen, goes back and forth swiftly, taking the reader along on the ride to the hospital and to what led up to it. In its pages, the stream of conscious narrative packs in a dizzying array of issues – mental health and the reluctance to acknowledge, recognise it in others and deal with it, the difficult negotiation between individual choice and collective consciousness, the pressure to be manly and bear with the required discipline that erases ‘yourself, your name, your moods, your emotions….’

Here is a soldier who is torn between what he knows has to be endured so that he can go back to ‘being a normal human being’ again, and his desire, rather his need, to resist the violence and regimentation of the larger Israeli collective. His is a mind that reads, that knows poetry as well as it does the Psalms. He feels suffocated amidst the ‘meaningless nonsense’ talk about comradeship and friendship. That is the only explanation he is capable of giving himself when all he is ever asked is what his problem is, why he cries, why it is not the army per se that he is incapable of being in, but just his base and so on. Yet, can he afford to be discharged from the army on a mental health card and have the stigma follow him for the rest of his life? Oscillating between the chronology of the weeks and months leading up to the drive and the journey itself, the novel is a tense, moving and brutally honest portrait of the complexity of mental health issues.

Reading The Drive in these times, in India and elsewhere in the world, feels nearly like a political act. The soldier’s mental conflict feels like our very own. Can we take a break from the new cycles, from being perpetually battle-ready, from speaking, writing, reacting and just spend a morning with a poem anymore? Can an individual abandon the collective and not invite the tsk-tsk of disappointment and loss of respect? In a society that requires its people to function almost like a single body and brain, how does one retain a measure of individuality and choice without being branded anti-something? The Drive, published as Neseah in Hebrew in 2011, may pertain to the specific dilemma of Israeli society, but the emotions it evokes seem a glove-fit for every crisis of national identity and every politics of patriotism. It is a novel that is really a manual for what it takes to be an individual in a country today.