The Soft and Hard City

In the 1970s, Dr Hans Winterberg, the director of the Max Mueller Bhavan in Hyderabad, wanted picture postcards to send to friends and family back home. Finding none, and being a keen photographer, he began shooting his own, seeking out monuments and landscapes. And then a fortuitous meeting with a professional German photographer, Thomas Lüttge led to a collaboration, with Hyderabad serving as their muse. As recounted by the editor, Heiko Sievers, “in endless car journeys, the duo roamed the dusty Deccan landscape…in search of ideal photographic locations”. In 1975 they were invited to put together a photo exhibition to showcase the heritage monuments of the city. They were invited again in 1995, to document the changes since, and then finally in 2012.

This is Golconda-Hyderabad 1975/1996/2012: A Photographic Essay by Thomas Luttge and Hans Winterberg, a distillation of two photographer’s journey, as well as a city’s trajectory.

Still, it is not a “then & now” reduction. As architect Pushkar Sohoni notes in the introduction, it is not a “simple mechanistic documentary process of juxtaposing two photographs”, but an effort to “extract a living history of Hyderabad and Golconda”.

The result is a film where the frames advance in decades, Time unspooling every year a frame, as they visit and revisit the same sites.

The collaboration ended with Dr Winterberg’s passing away a few years later after their last joint visit, but Thomas Luttge has been soldiering on, with another visit in 2014, when I had interviewed him, and yet again this December for the book launch. I had kept in touch and before the book’s launch I had a chance to visit him in Germany.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

I TAKE THE local train to the end of the line, to Wolfrathausen, a suburb of Munich. The station is drowsy in the heat when Luttge meets me, moving with a spryness that belies his seven and counting decades, and we drive down to his home. The Bavarian Alps fill the horizon; massive limestone massifs plunging upwards into the deep blue of a summer sky. We drive through the Bavarian countryside, past yellow chequerboard of mustard seeds, to his home, a 300-year-old converted barn, with whitewashed walls and low ceilings upheld by massive beams.

Evidences of his travels grace the room with statutes, rugs; the hall dominated by a Chinese silk print, picked up by a long-gone ancestor, a ship’s doctor on the Hamburg-Tsingtao run. Books are everywhere, I peek at a half-open one resting on a windowsill—Rescue of the Beautiful—Beauty in the Digital Age by a Korean philosopher.We sit in the garden, speckled by hydrangeas, making a tiffin out of Zuckerschnecken (sugar snails) and cheese.

He asks me Khajaguda, about Moula Ali, about Mir Momin ka Daira. Hyderabad hasn’t left him. He then proceeds to show me the prints that would make up the book. I marvel at a late afternoon shot of the Paigah tombs, bathed in golden light, taken in his first visit, in 1975. “You can only get that with film” he says.

Luttge is of a generation that was born in the convulsions of war, and subsequently renounced the values of the world that had birthed them. He describes leaving home at age 18, dropping out of college, and wandering around Europe for three months, armed with a Rolleiflex his father had given him. On that long ago summer, “I was on a country road in Greece. There was nothing behind me, no teacher, no money. There was a well. Water at the bottom. Sunlight coming at an angle”. He got his camera out. He remembers that photograph, that abstract play of layered shadows of the well, as when he realised his calling, in a satori like insight. “And this I have until today” he says of his father’s camera.

His day job was taking photographs of industrial facilities and processes, or equipment such as pump sets, paper mills, steel ropeways, and cars. His craft, in selecting the lens, in finding the right film, all were honed these years. “But I was not really interested to look at the final results” he says, “The product in the end, I didn’t find so interesting, there were just for some catalogues”. This restlessness would lead him around the world, chasing his own “visual dialogue”, working with the “raw materials (of) light and Time”.

ARCHITECT RAHUL MEHROTRA in his introduction talks about the hard and the soft city—the physical armature of the former hosts the “soft city of people and lives” going on to say that photography “cannot escape capturing the visual tension arising from the coexistence of soft and hard city in all its simultaneity and dynamism and in a continual state of transition”.

This tension of time is something that the photo essay returns to again and again. A stark black and white of an abandoned tomb in a necropolis, with only a bicycle propped up against the wall to mark the century. It arises out of geometries of the composition, the brushstroke of a clothesline against a whitewashed wall, backgrounded by a masjid on a hilltop behind. A phone number of a real estate agent scrawled in black paint over a cinder block wall, foregrounded to an abandoned palace, presaging what it seeks to replace. They are creative pictures, that must be felt, as the American photo-essayist Meatyard once said, in the same way as one “one listens to music, emotionally, without expecting a story, information or facts.” The captions however carry a dreadful cadence, “Interior, Malwala Palace (demolished),” “Deodi Iqbal-ud-Dowla (mostly demolished)” and so on in a depressing litany. For me, the most striking photographs are the black and whites of the Qutb Shahi tombs, where we see a long sloping plain, studded with the typical Deccan boulders, then leading up to the bulbous domes of the tomb. Lone cyclists or women are the punctuation to these carefully composed sentences. The critic John Berger said, “Between the moment recorded and the present moment of looking at the photograph, there is an abyss.” Nowhere is this felt more than here; let alone the photographs taken in the 70s, even the ones taken a decade ago already look from another unreachable era. The tombs, which were once clearly visible from a road near my home, are now completely occluded by encroachments. The boulder fields and low humped hills are all gone, so are the lakes, which doubled them. All around are the new buildings of Cyberabad, glass wrapped around a steel frame, endlessly reflecting each other, like a hologram of a city, a ghost city of light and photons, reflecting the insubstantialities of data exchange and electronic commerce.

Christopher Woodward, In Ruins, said that their material incompleteness, means that “each spectator is forced to supply the missing pieces from his or her own imagination.” Unlike the tombs, there is nothing to complete here, only mirrors reflecting other mirrors.

If an artist’s career is a catalogue of obsessions, then Luttge is drawn to the serrated skyline of the Golconda, the bulbous domes of the tombs, again and again. We first see them in a vast field, emerging from the basaltic plain, in stark monochromes, then progress to colour, and eventually encroached upon and occluded. If the city began as a fire in a poet-king’s mind, then these are the “the extant fragments of some lost and noble poem”. I think that at the shutter speed of 1/60, even a career of thirty years would really be a minute at most, of letting the light in.

LUTTGE HAS BEEN all over, from the backwaters of Bangladesh to the highest floor of the UN building in New York, from the souk in Marrakesh to the Wall when it came down. Hanging out with Werner Herzog, when they were students, to the sound that Osho’s Rolls Royce made on the lawn in Pune, when he met him. Yet unlike the raconteur, there is never any “I” in his stories, it is as if he is recollecting a dream, all unfolding and dissolving in a reverie of images.

Meanwhile, the deepening red-gold of sunset touches everything around us. I futilely try to snare the colours in my Instagram and try showing the results to him. He waves it away. He doesn’t believe in digital photography. There cannot be a positive, without a negative he declaims. He points to shooting in RAW format, with enormous data locked in, enabling endless editing, extracted from the binary code. But he dismisses all that. “But the information goes in all directions, goes into light and dark and all the colours and all these informations are there, but no definition, they are not defined. I mention all the possibilities, the filters, the edits. “A possibility is not an image” he says.

He mentions Wirklichkeit, the German word for reality. Something that you work on, and something that works on you. He tries explaining, “This approach is on two levels. One is the visible world. And at the same time, it’s also an inner world. And it’s not imagination, it’s more of a dream world. It’s the images that come up when you close your eyes, it can be a daydream. This is how we are made, that we have inner images that just show up. We don’t know why. But they come up. And we can work with them. You can access them or ignore them. But it’s the kind of inner world that you also see in the outer world. So that here is a connection between your own life and this inner world, and then you, you see it right there. And here two things come here. A world you can capture with the camera and at the same time, this specific thing you caught has something to do with your inner world.”

IT IS NOW EVENING, and we repair to his studio, where he shows the original prints.

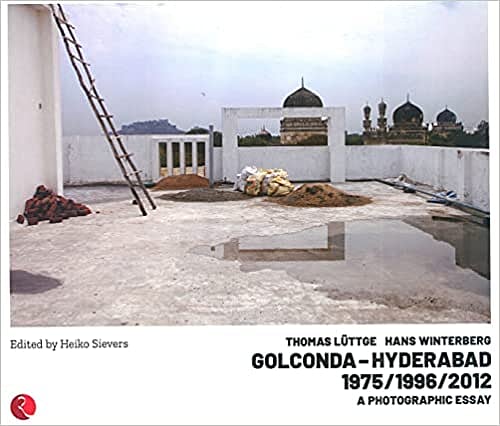

He has selected a cover for the book. Taken during 2012, it shows the typical daba of an under-construction house, which has come up just next to the tombs, with the usual bags of cement, bricks and sandpiles, Golconda in the horizon.

There is a wooden ladder leading upwards, to the water tank. I look closely. The ladder has a missing rung, the sky awaits above the frame, unreachable.