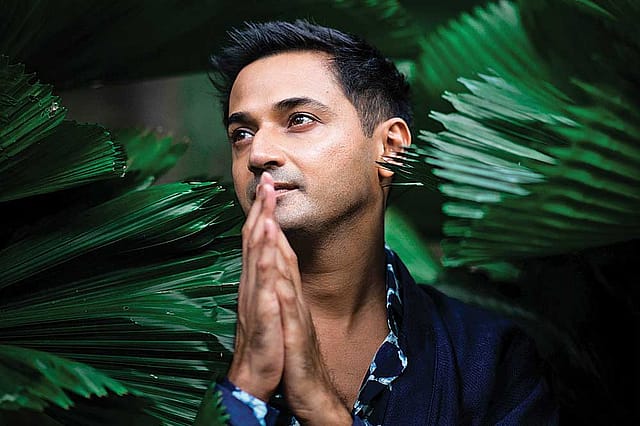

Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi: ‘To be truly adult is to be child-like’

SIDDHARTH DHANVANT Shanghvi's third offering The Rabbit & The Squirrel (illustrated by Stina Wirsén; Penguin; Rs 399; 48 pages) marks a sharp departure from his two previous novels, The Last Song of Dusk (2004) and The Lost Flamingos of Bombay (2009). The cover features a watercolour-style illustration of a rabbit and a squirrel perched on a giant rock, suggesting a children's book at first glance. The subtitle—'A Love Story about Friendship'—sets an equally innocuous tone. But by the time the reader makes it past the second page, she will realise the author has borrowed the condensed structure and simple language of a fable to narrate a story set firmly in an adult world of arranged marriages and spiritual quests.

Shanghvi believes that "to be truly adult is to be child-like". He emphasises that to be childish is a different matter altogether. The fable's form has always held an allure for him. Citing the examples of The Little Mermaid and Alice in Wonderland, he makes the point that these stories are "allegorical, timeless, heart-darkening". His mother read Hans Christian Andersen to him—a writer whose stories for children weren't without darkness themselves. He veers towards the child-like form of the fable because he has come to understand that "all greatness is a form of simplicity". Some other stories in this style—though not fables—that charmed him were The Velveteen Rabbit , The Little Prince and Winnie the Pooh.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

The Rabbit & The Squirrel is a slim venture with large lettering typical of literature for young children. Shanghvi's response to people telling him the book is short is to simply clarify, "No, it is complete." He credits the six years he spent curating art, films, photography and more at Sunaparanta, Goa Centre for the Arts, for teaching him "what to take and how much to leave behind". He says it was "the process of curating that led up to this book, in curating you learn to distil an artist's work to the most coherent, magic essence". His time as honorary director of Sunaparanta showed him how to "direct an institution and to lead it with responsibility, tact and care". It also taught him how to "do what writers often don't have to do— be properly sociable". However, he says he isn't part of a writing community in Goa or anywhere else.

The regular rhythm of his days in Goa begins with an early rising and a session of writing. He attends to routine household needs, checks and caters to the essentials—"Do we have fish, milk, rice?" After swimming at Morjim beach, he returns to the house to write. He is usually in the middle of work of some kind—either he is designing a house or curating a new show or writing. But ultimately, he prefers to think of himself as idle. "The notion that one has to do anything to define themselves is vulgar to me," he insists. Shanghvi's exhibition of photographs of his father, The House Next Door, in 2011, introduced a different side of his artistry to the public. He takes photographs regularly. He says he would like to do a show next year "if I find decent photographs in the archive".

The story's drawings are by an acclaimed and award-winning illustrator and writer from Sweden, Stina Wirsén. He says, "Wirsén possesses the rarest quality—grace. This lets her respond to the story as if she loves it more than I do, which might well be the case." In his opinion, her illustrations "have clarity, elegance, mischief, charm, subtlety". The collaboration between the two was effortless. Wirsén drew up the initial characters based on the story, and they slowly "fleshed them out scene by scene". He says, "As Sweden's most celebrated children's book illustrator, she brings the book a noble plainness—you can't bullshit kids; she knows this, so her art transmits a tender, lucid sincerity." He adds that the book's art director, Pompe Hedengren, Wirsén's husband, was a "marvel".

The fable's form may tempt a reader to believe that the cultural norms or personality traits and quirks attributed to different animals hint at a logic that comments on the social fabric of animals or humans. But Shanghvi says that he wasn't thinking along those lines, and the brutishness ascribed to the boar and the philandering for which the rabbit is well-known were incidental. He explains, "I started with characters, and then what interested me were the questions they were trying to resolve."

He similarly waves away the notion that the specific items (a bag of pine nuts and 3 kg of cherry tomatoes) gifted to the squirrel's family by the boar as a kind of trade for their daughter rest upon a deeper meaning. He has no idea why he chose those food items in particular: "It was all whimsical, the entire fable was pure whimsy."

His assertion that the narrative is driven by whimsy rings true. On the other hand, there is an inherent distrust of conventions at the heart of The Rabbit & The Squirrel. Shanghvi's fable tackles consent within marriages as well as sex coerced upon disciples at religious or spiritual groups as a key step in initiation and membership. Both the rabbit and the squirrel must navigate sexual demands made of them by people who are in positions of strength. They must contend with the possibility of loss should they refuse. Shanghvi's words are capable of a dark humour that undercuts the horrors to allow the story to flow rather than stall. It's a text of a few words, but the ideas it holds lend themselves to an endless taking apart and pondering over.

The fable includes the brief appearance of a manic-depressive at the monastery where the rabbit resides as well as an involuntary stint in an asylum for the squirrel. When Anne Enright, author of The Gathering (2007), was visiting Shanghvi in Goa, she told him her story of being institutionalised as a young woman. In retrospect, Enright found that it had been a kind of liberation for her because "once someone classifies you as crazy, you no longer care what anyone thinks". He also sees this experience as an "education in isolation" and "a shedding of the conditioned mind for the squirrel, who although a bit of a hippie herself, followed protocol and married the right rich candidate". But after her time in the asylum, she travels—"this is her freedom and education".

Shanghvi quotes a diary entry by Leo Tolstoy: 'This is the entire essence of life: Who are you? What are you?' He believes that a process of self-realisation commences for the squirrel after she forsakes the safety of married life. It's a minor subplot that's likely to attract debate in times where there is increased awareness of both mental health needs and of the involuntary institutionalisation of women who don't toe society's line. The economy with which the story is told is in possible danger of diluting the complexity of certain themes such as this one.

The squirrel's marriage is followed by the arrival of unwanted sexual attention and progeny that she cannot connect with. Shanghvi points to Anne Tyler's Ladder of Years (1995), a novel about a woman who one morning, without any particular grievance, abandons her family. He was fascinated by this premise, particularly as he sees most marriages around him in urban India "failing fabulously". In the squirrel's case, Shanghvi notes that "she's married to a tasteless, wealthy brute". The distance from her children emerges partly from a fear that "her children will be equally awful" as their father. He's interested in the idea of abandonment as a form of completion for protagonists in unhappy domestic circumstances.

Shanghvi is personally drawn to friendship and writing about it, as it is one of the "fundamental emotional structures" of his life—one that keeps him alive." "We think it lovely," he says, "when friendship crosses over into love; I hope for the exact opposite." He wonders why more writers don't turn their attention to the "structure and sustenance" of friendship the way Toni Morrison does in her 1973 novel, Sula, in which she explores the strengths and impediments of friendship. He laments that "this beautiful way of being, and an Aristotelian ideal, is relegated to commercial fiction". Shanghvi points to Andrew Sullivan's explanation of friendship: 'Friends will never provide what lovers provide: the ultimate resort, that safe space of repose, that relaxation of the bedsheets. But they provide something more reliable, and certainly less painful… they allow for an honesty which doesn't threaten pain and criticism which doesn't imply rejection.'

He explains that the rabbit and the squirrel are friends and "equals of heart" but aren't well-matched for a "conventional union" because they "are not social equals and are too solitary to live with each other". He sees their relationship as one unaffected by time. He says that both the squirrel's decision to try and live out her marital duties and the rabbit's choice to seek refuge in a monastery prove to be the wrong ones for them. Shanghvi says there isn't really a "right or wrong way to negotiate life"—the rabbit is disappointed by the realities of monastic life and domesticity cannot be enough for the squirrel. He points to the conclusion the rabbit arrives at in the book: "The only measure of time is the fun you have with it." Shanghvi clarifies that he doesn't "mean fun as mindless, frivolous time" but instead "the hours when one is most alive to life's questions, and alert to the beautiful impossibility of love, and its ability to satisfy us even after we concede it is impossible".

"When reunited," he explains, the rabbit and the squirrel "sense they have been immutably together, not in physical time but spatially. The division was physical, but somewhere, on a different plane, they remained where they had left each other. Without an aetiology for the end of the relationship, there had been no end." He traces this idea back to Virginia Woolf's 1925 novel Mrs. Dalloway: "Early in the book, the central character is out shopping for flowers when she recognises that all of time, the past, the present, the future, unite." For Shanghvi, the idea of "time without tense" is the "eventual consolation and justice" for the rabbit and the squirrel who experience "William Blake's noble premise of holding infinity in the palm of one's hand". When the friends meet again, they find "time had been a myth, separation a deception".