Shanta Gokhale: Body of Truth

IN THE 1980s when Shanta Gokhale worked at the pharma company Glaxo, one bad marriage behind her and the next, equally frustrating, just about beginning, she would walk into the office lawn at lunch, find shade under a tree, and sit with her back to the gate. With her left hand holding her lunch (a rolled-up chapati with vegetables), she would, with her right hand, write her first novel Rita Welinkar.

There was no other way. Gokhale was in her 40s then, running a house, raising two children, and making ends meet. “You know,” she laughs as she says this, “caught up in the usual chores women are trapped in.”

But she found what she calls “dribbles of time” and “slices of space”. The task of kneading the dough was suitably dull to think up characters. The bus rides to office were solitary enough for chapters to compose themselves in her mind. She could put them on paper over a quiet lunch.

The book—a Marathi novel where she used her observations of an extra-marital affair that had occurred around her—took her about four years to complete.

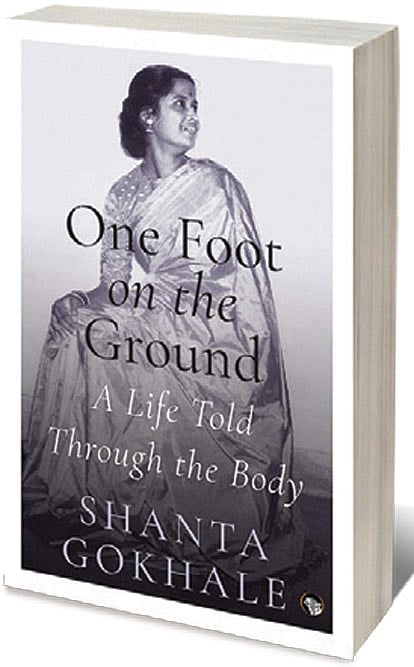

The next instance when free time presented itself was 17 years later. This was in 2005. Gokhale had been operated for breast cancer and prescribed nine months of rest. Her second husband had moved out by then and the children had grown up. You can almost hear her clap in excitement when she describes how she used this time to write her second novel in her recently-released memoir One Foot On The Ground: A Life Told Through The Body (Speaking Tiger; 252 pages; Rs 399).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

There are many things one can say about this memoir—how it tells the story of one of Mumbai’s most prominent literary personalities, or about how, using the story arc of her life, it examines what it means to be a woman in India. But the one thread running through the book, is the unstated petition for a woman to be given her space. In the case of Gokhale, space to pursue her literary inclinations.

Writing about the time when she was working on her second novel Tya Varshi (a story about a year in the life of a group of artists in Mumbai, later translated into English as Crowfall), even though this is the period when she was undergoing cancer treatment, she speaks of the immense pleasure of ‘singlehood’, of a pleasure not just confined to having her own space, work-table and bookshelves, but to also come in possession of her own ‘cool bed’. ‘I consider a cool bed a vital part of my singlehood,’ she writes. ‘A cool bed in which I can stretch my body any which way I like, throw my arms about, sleep leg on leg or legs wide apart. A body by itself, no move it makes arousing thoughts of possession in another. The independence to be yourself complete in yourself, is very heaven.’

I can see the cool bed today. It is a small commonplace bed with a large green bedcover which has been pushed to one corner of the room. We have moved here—from the living room, which is something of an old-fashioned balcony dotted with many plants, converted into a place to receive guests—into Gokhale’s bedroom-cum-work space. Here, all around is the evidence of a busy writer. There are notes and books on tables. A TV set and a cupboard stand at a distance, but there are bookcases and shelves everywhere else, crumbling under the weight of books. A sombre evening light from weeks of steady rains falls into the room. A computer sits at one corner. She points to it and without much heartburn speaks of how it crashed and took along with it some 40 pages of a new novel she is working on. “Now when you rewrite you find that you are not writing the same novel,” she says.

Gokhale’s house is as she describes it in the book. It is made of more doors and windows than walls. She has lived here for most of her life, having first moved into it along with her family when she was around a year old. “Almost as old as me,” she says. Around us, the neighbourhood of Shivaji Park is rapidly changing, with old houses such as hers giving way to more modern high-rises. There is some talk of cluster redevelopment, where houses including Gokhale’s could be pulled down and replaced by a larger building. “But it still has some life in it—20, 30 years maybe. I’m keeping my fingers crossed,” she says.

Gokhale occupies a unique spot in Mumbai’s literary and cultural scene. She inhabits that space where Marathi literature and drama intersect with English literature. For decades now, she has been here at this junction, critiquing and observing, translating and adapting, writing books, plays and film scripts, while also shepherding several newer generations of writers.

Even now at 80, the first half of her day is always kept open for others. People phone her or descend on this quiet flat, to seek her advice or to involve her in some literary project. She is to Mumbai’s literary scene, as a newspaper once described, what Gertrude Stein was to a generation of writers and artists in Paris of the 1920s.

Gokhale’s One Foot on the Ground isn’t a straightforward memoir. It employs a sleight of hand by telling the story of her life through her body. Thus the story moves as her body undergoes change, a childhood where she loses her tonsils and teeth, to the onset of puberty, to the birth of her children, menopause, glaucoma, a weakening voice, trembling hands, cancer. She borrowed this idea, she says, when she came upon the work of an American Buddhist monk, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, who teaches his followers to escape from worldly suffering by asking them to look at their bodies, organ by organ, and to accept them for what it is. While the spiritual objective of this pursuit didn’t interest her, its method, of looking at the body and its life not as incidental but central to one’s story, appealed to her as a writer.

It also makes for a fascinating premise. A woman’s body is a contested territory. There are demands of it, a constant series of battles over ownership. And it undergoes changes and provides its owners with such a variety of emotions, from shame and guilt to joy and happiness.

Gokhale had initially been hesitant to write a book about her life. “I’m a private person that way,” she says. “I don’t like the focus on me.” But her friend, the writer Jerry Pinto, had been pushing her for several years. The push became firmer when they began to collaborate on translations. “So he would come over often, and that gave him an opportunity to nag,” she says.

She managed to keep this at bay, until one day, she says, without any prompting, she began to recall in vivid detail, the memory of her tonsils being removed as a child. She was around six then. “I was amazed at how clearly I remembered the whole thing. Of how the chloroform felt, my throat felt later, the taste of the ice cream, and seeing those little balls of flesh in that kidney tray… I thought, ‘You know, if I can remember that so vividly, maybe my body memory is stronger than my memory of other things,’” she says.

Using the body to tell her story also had another appeal. She could tell the story of a common female body, she says, and arrive at a truth that was objective and verifiable, but in a way also outside of her. “Because if you are writing too much about yourself, your memory plays false,” she says.

That sounds like a cop-out from revealing too much about her emotions, I suggest. “Yes, yes, a cop-out,” she says and her trembling laughter fills the room. “It was a way of doing my story, where I could say to the publisher, this is my memoir... And at the same time, there was a distance that I was able to keep between myself and the story.”

Gokhale’s childhood in a progressive Maharashtrian family was happy. She writes in the book that in the late 30s, women who only looked at the ground beneath their feet, were the most valued. But Gokhale and her younger sister walked everywhere with their eyes boldly lifted, ‘looking at everything that was to see, including men if they came into sight’. But her later adult life, especially during her marriages, first to a naval officer and later to the filmmaker Arun Khopkar, was, as the book tells us, deeply unhappy.

Most of her literary output, the work that she is most proud of, blossomed only after she turned 60. Although we are only a few days away from her 80th birthday today, her schedule is packed. She has set aside most projects for now, to complete the translation of a well-known Marathi book (Shyamchi Aai by Sane Guruji), has already completed a non-fiction work on Shivaji Park, written a few plays, while also being mid-way through a new novel.

Writing—and certainly writing in Marathi—wasn’t at the forefront of her youth, when she returned to Mumbai after completing her higher education in the UK. Although she grew up in a bilingual household, her written medium of expression was mostly English. Her occasional pieces were for English newspapers and she taught English at colleges.

Later, when she had moved to Visakhapatnam with her first husband, a tough period, she began writing poems. She realises now that these poems were really a personal diary in verse, plagued by mental confusion, and hence inferior. But she did not know it then. Gokahle sent the poems to the poet Nissim Ezekiel, a former professor and friend of hers. Ezekiel’s reply came a few days later. He told her to give up on poetry altogether. Something about her long covering letter however had impressed him. So he suggested she turn to prose instead and to perhaps do it in Marathi (Ezekiel was encouraging people to write if they could in Indian languages). Another nudge later came from another friend, the theatre director and playwright Satyadev Dubey. He told her she was vegetating there (in Vizag) and turning into a cow, and mailed her a Marathi play Avadhya by CT Khanolkar (considered by some to be ‘the first adult play’ in Marathi) to translate.

Later when she moved to Mumbai, she found employment as a journalist at Femina, then as a PR executive at Glaxo, and later as the arts editor at Times of India, she was often approached by playwrights for translations. This was a period when Marathi theatre was going through a revival. A young crop of new playwrights were emerging who were creating controversial but groundbreaking works. On many occasions, these plays would face difficulty getting passed by the Censor board and the matter would land in court. “My friends in theatre wanted translations done [of their works] so judges could read what they were about,” she says. “So it [the translations] began like that.”

Outside, the light is turning weak. The road is beginning to groan under cars carrying office-goers back home. We have been speaking for over two hours, but Gokhale is untired.

I point out that the book, although an unsentimental account of her life, glows with compassion. Neighbours and relatives who slight, doctors who misdiagnose, possibly even fatally, hospitals and institutions that are cruel, all of them go unnamed. Sometimes there is even understanding. Husbands are named though. There was no way around that. But you get the feeling, as you sit talking with her today, if she could, she wouldn’t have named them even.

It is in a way a story of reconciliation. “Yes,” she says. All the questioning and answering has already been done. “It is about acceptance now.”