Set in Stone

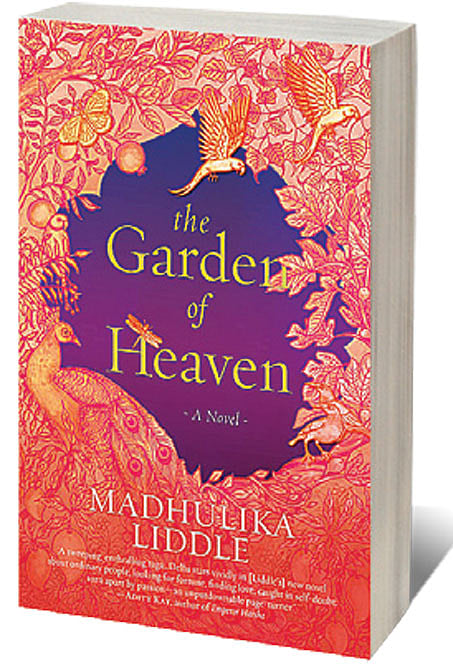

THE MOTIF IN Madhulika Liddle’s expansive novel, first in a quartet on the becoming and being of Delhi, is a stone frieze adorned with floral patterns and creatures with chiselled wings, to conjure the extravagance of ‘The Garden of Heaven’. The garden first appears in the story only around the midway mark, encircling Razia Sultan’s death, before a series of events occur that chalk the fate of Shagufta. The irony, however, is saved for the last when Shagufta the narrator describes the unimportance of the very garden of heaven that has directed her life thus far.

The saga has multiple stories running through it, decades pass between chapters, transforming the lands and the living. At the centre of these stories from different epochs is Shagufta, who, after having witnessed a brutal rampage in Delhi, must now survive on her own, along with a battered soldier from the enemy Taimur’s army. In the course of the ceaseless tumult, Shagufta chooses to tell the soldier stories of families that once were. Families that, as the reader is told, bear relation to both the personal history of Shagufta and to the city Delhi.

Liddle traces Delhi (or Dilli as it was known) and its adjoining areas through a little-known stone carver Madhav. The tombs and monuments, therefore, are shown under construction and not in their finished grandeur. The craftsmanship of labourers, who shape and carve stones, remains a task largely unrecognised as the creator gets all the credit—a situation that runs through another family of stone carvers Nandu, his daughter Gayatri, and granddaughter Jayshree—and finds credence in Shagufta’s narration. The inner lives of these carvers are detailed and vivid, much like the stones they bring to life. The ingenuity of this plot allows one to imagine the heritage sites of today—fondly associated with the emperors and the courtiers—as outcomes of the personal and collective struggles of the carvers and labourers who worked day and night to build them, for no recognition.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

For a fiction as vast and varied as The Garden of Heaven, Liddle keeps the form away from any unnecessary confusions, the sleek narrative keeps the reader engaged. The exchange between Shagufta and the injured soldier serves as a base for the stories to emerge—an ‘interlude’ that enables the reader to pause and recollect. The stories of the carvers and their families, of Sultans and their ambitions, as told by Shagufta, carry imprints of the oral storytelling tradition, signifying both the historicity and the authenticity of Liddle’s prose, which is both taut and unwavering. The prose can be heavy, reflective of the pre-modern/medieval setting of the novel, and serves as a portrait of the bygone ways of speaking and living.

Historical fiction, with its dual aim of historical veracity and fictional brevity, can be a fraught genre, more so today, when the lines between history and fiction are blurred. Liddle, with a prose in tune with the past it speaks of, skilfully pieces together a narrative from the definitive events of Delhi’s history. An evenness covers some of the characters she places at the heart of the stories: Girdhar and Razia, who challenge the status quo, Madhav and Shagufta, who’re equally unrelenting. The similarity between the lives of the characters gives the novel a “secular” shade, a recognition perhaps of the shared geography and history of the communities despite their differences. The most telling rift appears in the form of two invasions that occur during different epochs, and the bloodshed that follows. Liddle however situates brotherhood in this acrimony too by making the narrator protect and provide for an enemy soldier. More importantly, Liddle highlights the act and the process of storytelling, its ability to pass time, heal, and sustain. These are stories that live beyond the teller, moving between generations and time—tying the vicissitudes of the present with the happenings of the past.