Search Party

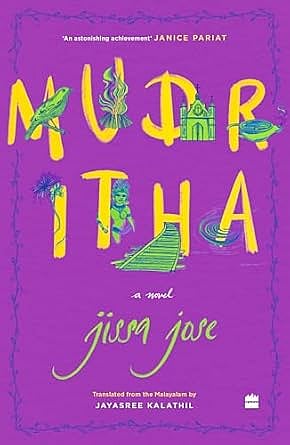

Far from being a debut novel exploring the lives of the ordinary women of Kerala, Mudritha (first published in Malayalam 2021) is a torrent unleashed by Jissa Jose and now translated into English with exquisite sense of place by Jayasree Kalathil. Jose is the Principal of the Government Arts and Science College, Thalassery; we are told in the author’s note. She has a PhD from the University of Kozhikode and has written four other novels and has received much acclaim for Mudritha which is in its sixth edition. Jose is originally from Kottayam. While Jayashree Kalathil who is originally from Kottakkal in the Malappuram district of Kerala, currently lives in New Forest in Hampshire, UK.

Mudritha the main character, cannot be called the heroine, for there are no such certainties here. The novel washes over the backwaters of the familiar landscape of Kerala suffused with its rich tropical lore and dense mythology seeping into the decay of a past that’s enshrined in the rituals of brass lamps filled with light. It asks difficult questions that challenge the tropes of Kerala’s strong matrilineal women striding through their once impregnable homes, servicing the men that have hitherto endorsed, if not created the myth. It’s not patriarchy that is under siege here, but the matriarchy wielded by the strong women in their starched bleached cotton, gold bordered garments—whether in the inner chambers of their dark wood panelled homes, or deeply veiled in nunneries and zenanas. The beam of Jose’s klieg light gaze penetrates through the chinks and crannies of the inner lives of nine different women who appear to have been randomly selected for the journey.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Very much in form like the Canterbury Tales of Chaucer the nine women are part of an online Chat group named (let us not snigger) “Lesbos”, who take up the offer of a train journey to Orissa. Some of them have not been on a train. Once cannot call it a yatra, or a sight-seeing tour. There are hints of a temple dedicated to women on the banks of a river named Chitrotpala, which like Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro haunts the young tour organiser Aniruddhan, who has been co-opted by the woman who calls herself Mudithra. She engages with the outside world by email. The trip is an escape for the women from the drabness of their lives. They are middle-aged with nothing much to recall of their youth except the aridity of loss. The nine lives could also be said to represent the nine “rasas,” or the nine essential emotions.

However strident this sounds, Jose does not fall into the trap of creating victims and predators. She doesn’t even mention class and caste except in the most tangential ways. There is a certain refinement in the way she unravels the lives of the nine women plus Mudritha. She lets them speak to us through the net of literature and the traces left by earlier women writers and poets. Each of the women is given a name and let loose to float like different coloured kites that are pulled together by the force of Mudritha. Through them Jose recreates the legends and myths that have been woven around women in different cultures. As she writes about one of her characters, Madhumalathi a teacher, towards the end: “If she were to write a textbook, it would be a book about human beings, Madhumalathi was certain. A book about ordinary people from various time periods, and about the ordinary experiences of those who ruled them.”

The book fittingly starts with a reference to a poem by Zeynep Hatun, the 14th-century Turkish poet, who writes in the Sufi tradition: “I am the traveler. You are my road. / I go from You to You.”