Scene by Scene

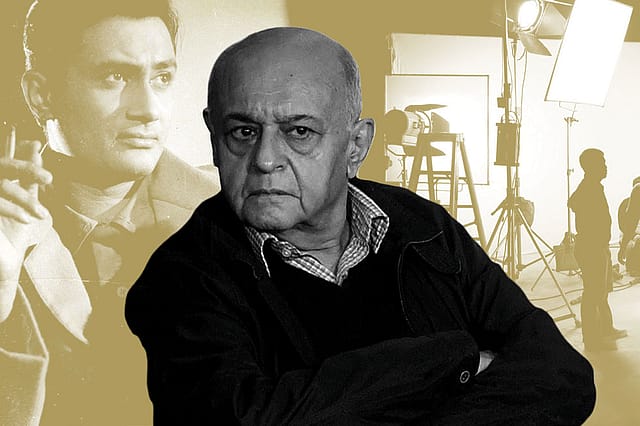

HE’S PLAYED BADMINTON with Dilip Kumar; been there when Dev Anand met Suraiya, after 30 years; and been whisked away to Nargis’s personal physician by her when he showed signs of fever. Amit Khanna has been there, done that, so when he offers his understanding of popular culture in India, it’s only wise to listen.

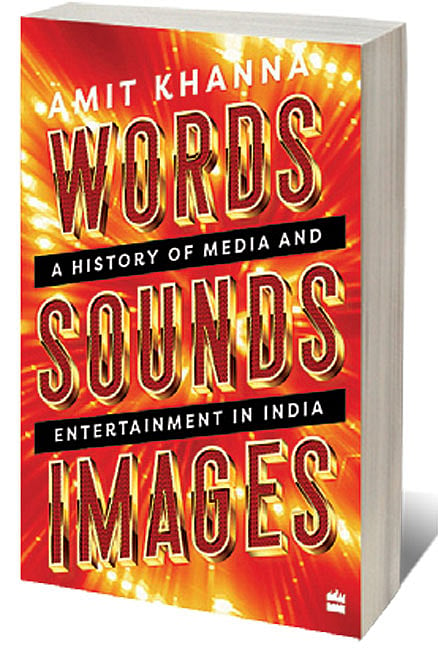

In a new book, Words. Sounds. Images: A History of Media and Entertainment in India, the man who created the country’s first synergised production company, Plus Channel, that did everything from news to entertainment, recreates the history of Indian popular culture, from Bharata’s Natya Shastra to digital streaming shows. Divided chronologically, he captures the changing trends, from the spunky women who ran film studios in the thirties to the return of the native in the cinema of the 2020s, from the famous trio of Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar that ruled in the 1950s to the 24X7 digital entertainment of today.

But the book is about more than Indian cinema. It is about the entire gamut, from print to radio. Words. Sounds. Images has it all—whether it is the rise of sassy film journalism in the 1970s through Stardust and Cine Blitz or the beginning of satellite television in India (Khanna was an early bidder for Hutchison Whampoa’s AsiaSat transponder which was ultimately bought by Subhash Chandra who started broadcasting Zee TV).

The tone is straightforward and only rarely does the writer allow himself the luxury of being centrestage, with delicious results—from seeing Alia Bhatt as a child accompanying her father to his Plus Channel office, which Khanna started and where Mahesh Bhatt was creative director, to meeting Bappi Lahiri as a pudgy tabla prodigy. But for the most part, Khanna who was persuaded by Dev Anand to head his production house sticks to telling the story of India’s soft power.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Through the glorious decade of the 1960s to the defining decade of the 1990s to the digital decade of 2010s, Khanna has always been able to see the future of the attention economy. It could be the Rs 2 lakh he spent to buy a gigantic personal computer when it first came out in the 1980s or the informal merger with Reliance Entertainment and launching its Hollywood business, Khanna, who is an avid reader, has an instinct for what the future will look like. It is a natural intuition honed since the early ’70s when he first became a part of the entertainment industry. If the Indian establishment understood the importance of sort power, it was in no small measure because of the hours Khanna put into industry bodies such as The Film & Television Producers Guild of India and Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry. When he joined the guild he was in his twenties and the older members protested that he argues too much.

But it is precisely his arguments and interventions that gave the scattered studios and the multiple production houses much needed visibility. The book takes us on a journey from the frugal India of the 1950s to the zipless consumerism of the noughties. But Khanna has remained unchanged, never wallowing in nostalgia and always looking ahead.

Khanna is a poet and lyricist. He has been a director and producer. He has made TV serials and produced news bulletins. Through it all, what has motivated him is not money but ideas and the thrill of discovery. Which is why perhaps his greatest wealth is the 800 people who have worked with him at some point. Learning. Striving. Telling our stories to the world.