Questions of Identity

What does Islam mean to Indians, Muslim and non-Muslim

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

21 May, 2021

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

21 May, 2021

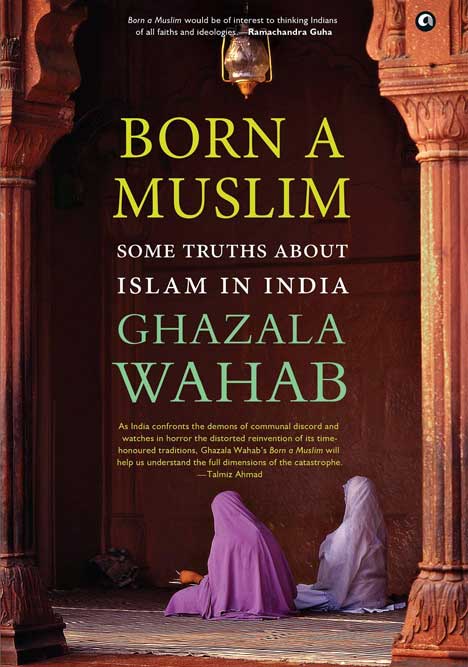

/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Islam1.jpg)

Jama Masjid, New Delhi (Photo: Getty Images)

When David Davidar of Aleph, India’s most perceptive literary critic, sent me my review copy of Born a Muslim, his covering letter said he expected this to be the most important book he would be publishing in 2021. As it was still the first quarter of the year, I could only wonder how he could be so sure. But having read it, I think it has already risen to first place in my choice of Book of the Year.

Ghazala Wahab comes from a family that was ‘poor and illiterate’. She was born in a Muslim ghetto in Agra, which was ‘riddled with poverty, illiteracy, backwardness, and unthinkable danger’. Her lane was ‘canopied by crisscrossing electric wires’. There was a ‘permanent police presence at the mouth of the lane’. Yet, hers was a happy, if pious, childhood from which two features stand out: ‘the world view of the women in my family was extremely limited’ but her father and grandfather ‘had several non-Muslim friends and business associates.’ She grew up ‘inclined towards Sufism’ which, she says, finds its connection to Islam ‘in the flexible religious practice of the dargahs’.

In 1983, when Wahab was about 12, her father and the nuclear family moved to a neighbourhood ‘inhabited by Brahmins and Baniyas; we were the only Muslims there.’ The move was made possible because her father ‘had become one of the biggest Indian exporters of footwear’ to the Soviet Union and other East European countries, including the German Democratic Republic. He was also honoured by the Government of India for his innovative designs and export performance. Indeed, he was so successful in his business as to suggest that his 16-year-old daughter might consider going to the US for her higher studies. ‘Had I gone to the US in September 1989 as planned,’ she remarks wistfully, ‘I would have missed out on the life-altering events that had started to unfold in India.’ What were these ‘life-altering’ events?

She had joined a journalism course at Delhi University but was intrigued that, unlike her school friends, ‘nobody asked me anything’ about Islam. ‘In fact, none of them had any curiosity about Muslims.’ This was the vacuum into which communalism poured its vitriol. The majority community knew so little about the largest minority and were so little interested in learning about their way of life that when LK Advani started his Ram Rath Yatra in September 1990 (with an unknown RSS pracharak called Narendra Modi in tow), he could spread his poison with few questions being asked by his growing band of followers about the essential humanity of their 14 percent minority of fellow-citizens. It was easy to convert indifference into prejudice and ignorance into violence.

Wahab’s own growing up received a shocking blow in November 1990 in the aftermath of Advani’s Ram Rath Yatra. It is best described in her own words:

‘My family, who had no previous experience of communal violence, was in a dilemma. We didn’t know where we would be more secure – in an upscale Hindu-majority neighbourhood, where the privilege of the residents would throw a security blanket around us, or in a Muslim-majority lower middle class neighbourhood where our numbers would isolate us…As the communal situation started to worsen all over north India, I was asked to come home.’

It was the moment of reckoning not for her alone but for all of us, majority or minority.

‘Home’ was her family bungalow in an upmarket Hindu-majority area of Agra. That, alas, provided them with no protection—for that is where communalism came to meet them. It started with slogan shouting, followed by the sound of the windows of their house being stoned and smashed. An impetuous uncle picked up his gun. Wahab’s father told him to put it down. “You fire one shot in the air, and they will burn the house down.” It was not till ten at night that their well-connected family, ‘with a vast network of friends among the bureaucrats who had served in Agra’, were able to get the police to turn up.

‘Home’ was Ghazala Wahab’s family bungalow in an upmarket Hindu-majority area of Agra. That, alas, provided them with no protection—for that is where communalism came to meet them. It started with slogan shouting, followed by the sound of the windows of their house being stoned and smashed

The next morning her cousin, five years younger than her, came to the house from the mohalla quaking with fear and a gory story of how the police had suddenly arrived, thrown a dragnet around the area and taken away all the menfolk to the thana, where they were mercilessly thrashed before being released late in the evening.

Wahab accompanied her mother to their ancestral home. The open maidan at the entrance to the locality was like a ‘war zone’, with stones scattered all over the unpaved ground and—in an unforgettable image— ‘carcasses of two-wheelers’. Windows were broken and doors were hanging ‘by their hinges’. Worse was to follow. On entering their old family home, they found the TV set smashed, ‘lying face down on the marble floor’, ‘pieces of glass, remains of crockery…and the heirloom copper paandaan’ scattered among other debris. Her aunts, ‘distraught and dishevelled’ hugged her mother ‘in a frightened collective embrace’. The police had come in that morning, ‘dragged my uncles out in their sleepwear’ to inflict ‘ugly welts’ on their bodies for the crime of belonging to their religion, then returned to ‘deliberately break things’. Wahab’s poignant conclusion at this barbaric vandalism by those who were required to protect them was that her father and one brother might have ‘travelled a small distance from the Muslim mohalla to an upper-class Hindu colony but emotionally they had travelled the distance of a lifetime…when it came to communal division, they were nothing but Muslims. Forever suspects, forever scapegoats.’ That is the measure of our national descent.

It was this encounter with the ‘new realities’, brought to the fore by Advani’s Ram Rath Yatra and all the way through Bombay (1992-93) and the Gujarat pogrom (2002) to the riots in north-east New Delhi in February 2020, that led to the questions posed in this book: ‘what did Islam mean to Indians, Muslim and non-Muslim?’ Could this be ‘a question of identity itself? An Islamic identity superimposing itself on the Indian Muslim identity?’ As well as ‘bigger issues’ like ‘insecurity, discrimination, injustice, and criminalization?’ She addresses her answers to ‘both Muslims and non-Muslims’. To fellow-Muslims she asks: ‘Is it not possible to be Muslim and forward-looking?’ To non-Muslim Indians she seeks to explain ‘how their perception of Muslims is based on hearsay, not facts’ in the hope of building ‘a bridge of conversation’. This is what imparts to this book its unique distinction. It neither raves nor rants against ‘Hindu’ iniquities; nor does it indulge in hyperbole about her own community. She looks for practical solutions in thought and action, focusing principally on what Muslims can do—and are doing—for themselves. This is the authentic voice of one who does not regard the expression ‘Indian Muslim’ as an oxymoron. Wahab affirms that one can be both an Indian and Muslim.

From where then do the principal insecurities of the Muslim community arise? Ideologically, Wahab says, from the view of the RSS leader, MS Golwalkar, who claimed that Indian Muslims do not view ‘Pakistan’ as the culmination of their endeavours but ‘as a first step towards establishing the Islamic Empire’. On the other side, this was reinforced by Hafiz Saeed of the Hizbul Mujahideen proclaiming from Pakistan that Prophet Mohammad himself had raised the war cry of ‘Ghazwa-e-Hind’ – the conquest of India, to which the ‘Indian Muslims, being fifth columnists, will rise in support’. Although most Indians, whether Muslim or non-Muslim, have not even heard about either of these propositions, Savarkar’s propagation of a new political philosophy that he termed ‘Hindutva’— ‘Hinduize all politics and militarize Hindudom’ – fed into these perceptions, at first insidiously for nearly a century. Then, from the 90s, climaxing in the second decade of the 21st century, the virus viciously attacked the main body politic.

These ideological issues were reinforced by Savarkar’s precept being brought into practice by the ruling establishment: ‘Nothing can weld peoples into a nation and nations into a state as the presence of a common foe. Hatred separates as well as unites.’ In Pakistan, the common external foe fits the bill; within the country, the Indian Muslim is the obvious target. ‘The focus of Hindu communalism,’ writes Wahab, ‘remains Partition’.

This is accompanied by the blatant distortion of history. As the author bemoans, ‘historicity means little in the face of belief’. The claims made and spread by propagandists seeking to prove that the Muslim invaders were atavistic barbarians rests on the dubious assertion that Muslim rule destroyed 60,000 Hindu temples. The fact, as unearthed by the historian, Richard M Eaton, is that archival and literary records document ‘eighty instances of temple desecration whose historicity appears reasonably certain.’ Whether it was 80 or 60,000, this has to be weighed against the fact that ‘much before the arrival of Muslims in the subcontinent’, ‘the destruction of temples was commonplace in India as a mark of victory’ since powerful Hindu kings generally endowed temples as a sign of their power, inviting desecration or destruction by those who overthrew them wanting to show the populace who was now in power. Romila Thapar has indubitably established that this was even the case at Somnath, whose first invader and looter was not Mahmud of Ghazni but a series of non-Muslim conquerors. Such false propaganda also draws the veil over the fact that ‘once the Muslims assumed power in parts of India, they often [became] benefactors of temples’.

But whatever the ideological fault lines and perversions of history, the Partition of 1947 was an indisputable and evident fact. ‘Muslims,’ says Wahab, ‘who chose to stay in India after partition internalized the blame, weighed down by the guilt of dividing the country. This guilt has shaped their post-Independence politics in India. Not only were they made to feel unwelcome, but they also accepted this ignominy as atonement for their supposed sins’. She quotes Mohammed Adeeb, who was a colleague of mine in the Rajya Sabha and a very good friend, as saying, “Muslims forfeited their right to pursue their politics after Partition. Their only hope today is to stand with secular Hindus.”

Adeeb does not add (although I am sure he will agree) that there were plenty of secular Hindus who stood by the Muslim minority and plenty of political parties that proudly proclaimed themselves ‘secular’, as also communitarian parties like the Indian Union Muslim League who were indestructible in their areas of concentration. But, yes, Najeeb Jung, the former IAS officer and Lieutenant Governor of Delhi, is right in pointing out that ‘the manner today’s youth take to the streets to assert their rights’ perhaps shows that ‘the present generation of Muslims has shrugged off their parents’ guilt’. Tragically, radicalised Hindu youth of the same generation have gone in the opposite direction—and taken numbers of their parents with them. Thus, the India that reacted to the horrors of Partition by following the Mahatma and Jawaharlal Nehru into a secular nation, that regarded the protection of the Muslim minority and the promotion of their interests as a civic and constitutional duty to be performed in a spirit of compassion and large-hearted generosity, have taken to calling the humane treatment of our minorities, particularly Muslims, as “tushtikaran” (appeasement), twisting the tale to say, “Hindu khatre mei hai” (The Hindu is in danger).

To fellow-Muslims Wahab asks: ‘Is it not possible to be Muslim and forward-looking?’ To non-Muslim Indians she seeks to explain ‘how their perception of Muslims is based on hearsay, not facts’ in the hope of building ‘a bridge of conversation’

The relative calm of the ’50s was disturbed by the outbreak of an average of six riots a year over the next three decades. The author walks us through Jabalpur (1961), Ranchi (1964), and the ‘biggest riot’ (Ahmedabad, 1969) – which brought to the surface the ‘underlying distrust bordering on hatred between the two communities’ that caused insecure Muslims to slink ‘into their ghettoes’ and created border lines within the city ‘menacingly referred to as Hindustan-Pakistan’. Jamshedpur (also 1969) marked the advent of ‘loud cries of Jai Bajrang mingled with stone throwing’. The ’70s were a decade again of relative calm until Moradabad (1981) shot us out of our complacency. The police firing at the Eidgah marked ‘post-independence India’s Jallianwallah Bagh’: ‘the cold-blooded massacre of Muslims by a rabidly communal police force’, as activists Sharjeel Imam and Saqib Salim were to later describe it. The protests and riots spread through much of Uttar Pradesh. There followed Meenakshipuram (1981) in the deep south where RSS cadres protested the ‘mass conversion’ of the scheduled castes to Christianity. ‘Major conflagrations’ broke out in 1982 at Meerut, leaving 90 Muslims dead, ‘42 of whom were killed by the PAC (Provincial Armed Constabulary)’. Then came the horror of the Nellie massacre in Assam (February 1983) ‘which killed between 1,800 to 3,000 people in the span of a few hours…spread across several villages inhabited by Muslims of Bengali origin’. She also vividly describes the post-Babri Masjid destruction riots in Bombay (1992-93) and the retaliatory Muslim-led bombings of March 1993, and from the Gujarat pogrom of 2002 right up to North-east Delhi (February 2020) marked by the infamous slogan coined by a minister of the BJP central government, “Goli maro saalon ko” (shoot the f*****s – my translation).

1984 saw communal violence of a particularly brutal kind break out between Hindus and Sikhs, first in Amritsar ‘that officially left 2,733 people dead’. That paled into public amnesia when, following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, pogroms against the hapless and defenceless Sikhs took a toll of some 3,000 in Delhi alone and several thousand more in the country as a whole.

This prepared the ground for the most lasting of all communal issues that has bedevilled our land from the mid-80s into contemporary times: the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi (BM-RJB) dispute. Wahab does a superb job of reversing the conventional chronology of events to show that the Vishwa Hindu Parishad had started the agitation over BM-RJB as early as April 1985 (the same month as the Supreme Court judgement on the Shah Bano case) by taking out a Rath Yatra from Sitamarhi to Ayodhya and that the locks at Ayodhya were opened on January 31st 1985, a month before the Muslim Women (Rights on Divorce) Bill was introduced in Parliament by the Law Minister on February 25th. ‘This sequence of events,’ the author points out, ‘shows that Muslim communalists were placated only <after> Hindu communalists had been accommodated’ (emphasis added). She also points out that it is hardly possible that Shah Bano was ‘destitute’ or in imminent danger of ‘vagrancy’ as she had been married for 46 years and ‘her first-born would have been at least 40 years when she divorced’. Second, Shah Bano herself never availed of the derisory maintenance grant of Rs.179.20 per month granted her by the High Court and confirmed by the Supreme Court, and yet survived for decades.

But having quoted Arun Shourie in conversation with her as having said, “When the Rajiv Gandhi government reversed the court order on [the] Shah Bano case, it was seen as the capitulation of the secular forces in the face of irrational religious ones,” she fails (and this is the only point on which I would fault her) to mention that in Danial Latifi the Supreme Court ruled in 2001 that far from ‘reversing’ the 1985 Supreme Court judgement, the 1986 Act actually ‘codified’ the verdict and did not violate any article, including 14 and 21, of the Constitution, as alleged by the very senior and highly respected senior advocate with a Muslim name but Marxist convictions, Danial Latifi.

The highly communalised atmosphere was aggravated by the highly communalised PAC in Maliana, a locality of Meerut city and, in quick succession, at Hashimpura (May 1987). This was followed by the massive election-eve riot in Bhagalpur, Bihar (October 1989) provoked by the VHP’s Ramshila processions. The BJP gained political advantage from this and consolidated its electoral advantage by becoming crucial to the formation and sustenance of the VP Singh government that lasted 11 unfortunate months. It was brought down by the Advani Rath Yatra that Advani claimed was peaceful but, as the author shows, was actually Advani’s blood Yatra as, in its wake and elsewhere in the country, hundreds of innocent lives were lost to brutal mass murder, with Muslims bearing the ‘biggest brunt’.

Wahab says that no Muslim can win against competitive sectarianism in today’s India. Their only hope is to fight sectarianism through inclusive and progressive politics

Then came the desecration and dismantling of the Babri Masjid (December 6th 1991). It fundamentally altered Hindu-Muslim relations by aggravating ‘the sentiment that drove the violence’. Wahab was then 20. She has lived the last three decades of her life under the shadow of that ‘barbaric’ act of ‘egregious violence’, to quote the Supreme Court in its 2019 judgement. ‘This,’ she says,

‘affects the psyche of the community, its relationship with itself, and with others. Frightened people cannot think clearly…Today, both Indian Islam and Muslims need to embrace modernity…But it can only happen if the community feels secure and at peace. The current atmosphere in India is the exact opposite of that. It is inducing fear, self-pity, as well as latent anger. Nothing good can emerge from this.’

And yet there has been a countervailing reaction from significant sections of the community—especially a new breed of Muslim politician, Muslim women, and a new generation of Muslim youth.

Thus, in sharp contrast to the Indian Muslim politician of the 20th century who placed the fate of the community in the hands of ‘secular’ parties, there is the nascent rise of politicians of a new ilk like Asaduddin Owaisi, whose ‘erudition sits comfortably with his overt Muslim identity’. While his brand of Muslim politics is ‘combative and assertive’, he underlines that ‘there is no Muslim leadership. I am a representative of my people, not just the Muslims’. I recall the awe with which I watched him take on in Islamabad a Jamaat-e-Islam ideologue on Pakistani television for suggesting that it was Pakistan’s duty to protect the Indian minority. He lashed out at the speaker in mellifluous Urdu damning the Pakistan movement for having divided the Muslim community of the subcontinent into three countries and holding that Movement responsible for all the ills that had befallen their Indian co-religionists. We have no need of you, he thundered.

In India, as the author underlines, ‘Owaisi insists that his brand of politics is positive and does not depend on fear of the Other.’ All he seeks is that Indian Muslims ‘must look beyond their fears; that they must assert their rights which the Constitution of India guarantees them’. In varying degrees and in different idioms, there is a similar turning away from Jinnah and Pakistan and the hangover of Partition to look to themselves self-confidently as both ‘Indian’ and ‘Muslim’, such as the venerable Shia leader Maulana Kalbe Jawad (‘Muslims have repeatedly been let down by those who claim to lead them, starting with Jinnah’); Arif Mohammad Khan (who, alas, has confused being an ‘Indian Muslim’ with aligning himself with Hindutva); Badruddin Ajmal in Assam (who has ‘a tough time performing the balancing act between being overtly religious and secular’); Hamid Dalwai (a ‘dissenting reformer’); Kamal Farooqui of the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board (whom I would describe as a ‘conforming reformer’!); and Ali Anwar of the Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz that seeks to serve the needs of the low caste and low class Ajlaf and Arzal communities of Muslims, as against the traditional Muslim political preoccupation with high-class Ashrafi interests. She also invokes the ‘protest poetry’ of Hussain Haidry and Aamir Aziz. But I profoundly regret the author has not included my Foreign Service and parliamentary colleague, Syed Shahabuddin, an ardent patriot and a brilliant and bold fighter for ‘Muslim India’—an expression that needlessly annoys right-wing Hindu extremists. She concludes:

‘No Muslim can win the battle of competitive sectarianism in today’s India. Their only hope is to fight sectarianism through inclusive and progressive politics.’

Shaheen Bagh was a movement imbued in a secular idiom, eschewing any religious overtones, and symbolised by the waving of the Indian tricolour and readings of the Preamble to the Constitution, totally non-violent, totally patriotic and nationalistic, demanding only their constitutional and civic rights, upending the monopoly on nationalism

Nothing is more illustrative of this wise advice than the Shaheen Bagh sit-in demonstrations (December 2019-March 2020) that shook up the nation as never before. The spark, in Wahab’s telling, was lit by ‘a widow of many years’, Tarannum Begum, who, on hearing that the police had entered the Jamia Millia campus and assaulted the students within, stormed out of her house screaming “Ab nahi tho kab?” (If not now, then when?) Many others like her also poured into the streets, braving the winter cold, recalling to the author the famous lines of Majrooh Sultanpuri: “Mei akela chalatha janib-e-manzil magar/ log aate gaye, karwan banta gaya” (I had set out for my destination all alone/ but people kept joining me, and we soon became a caravan). ‘Within a week, the Muslim women of Shaheen Bagh, erstwhile home makers, some barely literate, had found their real calling’ opposing the various legislative and administrative moves that threatened their citizenship of India. It was a movement imbued in a secular idiom, eschewing any religious overtones, and symbolised by the waving of the Indian tricolour and readings of the Preamble to the Constitution, totally non-violent, totally patriotic and nationalistic, demanding only their constitutional and civic rights, upending the monopoly on nationalism claimed by the Hindu right.

In next to no time, mini-Shaheen Baghs started sprouting all over the country. In my constituency alone, thousands of kilometres from the epicentre of the protest, I addressed as many as three such gatherings and could, had I the time, have addressed at least a dozen more. The common refrain was, “I will not hear from anyone that I am not an Indian and this is not my country”. Tarannum Begum added, “I have met more non-Muslims in these four weeks than I had in my entire life.”

‘It appears,’ says Wahab, ‘that never before have Muslims been more secure in their Muslimness. Their confidence in their Muslim identity and the ensuing assertiveness has suffused both the physical and cyber world… Is this the face of Muslim society? Self-assured and assertive?’ While there is as yet no definitive answer to these questions, there is no doubt that where politicians of all hues crumbled in the face of Hindutva electoral victories, the women and youth of all religions who gathered for three life-altering months at Shaheen Bagh have shown the Hindu right that they cannot be taken for granted and that ‘the changing face of Muslim society’ will not take lying down their right as Indians to equal treatment with their fellow-citizens. It was only the onset of Covid-19 that drove them back to their houses. They will return as soon as any attempt is renewed to undermine their Indianness.

For the new role of Muslim youth, the author quotes a young lawyer and activist, one Anas Tanwir, who argues that:

‘Muslims chose to stay in India in 1947 because it was going to be a multicultural, secular state with one of the world’s most visionary and liberal constitutions. Those who wanted a theocratic state migrated to Pakistan.’

Tanwir goes on to cite Maulana Azad in the immediate aftermath of Partition proclaiming from the steps of Delhi’s Jama Masjid:

‘Come, today let us pledge that this country is ours, we belong to it and any fundamental decision about our destiny will remain incomplete without our consent.’

The post-Partition generation of Muslim politicians, especially after the passing away in 1958 of the Maulana, failed to follow up that assertion of the role of the Indian Muslim in nation-building. The present generation of Muslim youth is retrieving the spirit of that perception. They are demanding their rights not as Muslims but as Indians, principally because their rights as Indians are being denied to them because they are Muslims. Shaheen Bagh’s lasting contribution has been to awaken the community and the country to the indubitable fact that, numbering nearly 200 million, no ‘fundamental decision’ about their ‘destiny’ can be taken without their ‘consent’.

As for the new role of the ‘erstwhile homemaker’, the Muslim woman, even the articulate author has to take recourse to the little educated Tarannum Begum:

‘We kept quiet when the Babri Masjid was martyred, and the highest court of the land did not do justice to us. We kept quiet when innocent boys were killed… and labelled as terrorists. We kept quiet when our livelihoods [were] threatened by the closure of butcheries and curbs on meat and the leather trade…We kept quiet when the government made the law on triple talaq, turning our men into criminals. But if we keep quiet now, we may even be thrown out of our land…This is about our Constitution, about our country.’

Wahab’s enduring solution to the problems of Indian Muslims does not lie in any expectation of reforming Hindutva and its followers. They are incorrigible. Also, as ‘Indian Muslims have been victims of systematically cultivated prejudice… the slogan of ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’ is meaningless for the Muslims because it assumes all communities are equally impoverished. But a large part of the Muslim population is much worse-off than many other minorities.’ This has been proven by the Justice Rajinder Sachar report.

Wahab believes the answer for the community lies in themselves, above all in the ‘small middle-class that has emerged over the last few decades’ and ‘the embrace of modern education by a growing number of Muslims.’ Partition was sought by, and most profited from, by the better-off Muslim (shurafa) who had little compunction about leaving behind his lowly fellows in the Dar ul-Harb. This was particularly true of India north of the Deccan. The south, apart from Hyderabad and pockets of the former Nizam’s domains, was barely affected and, therefore, the Muslim of the south faces nowhere near the threats that are growing increasingly grave in the rest of the country, particularly the Hindi heartland.

There is a major role here, says the author, for Islamic philanthropy. Annual zakat collections amount to around Rs. 50,000 crore a year. There are besides Muslim ‘millionaires, upper-middle and middle class’ who need to be tapped to create a Muslim welfare fund led by a reputable organisation like Aziz Premji’s Wipro or the famed Hamdard. Recognising that setting up new schools, vocational and coaching centres, and institutions of higher education will take time and effort, the author pleads that the ‘madrassa’ system be left alone as students at madrassas ‘mostly come from extremely impoverished backgrounds…Madrassa education offers them free boarding and lodging and the possibility of employment in some mosque.’ So, ‘instead of the proliferation of madrassas, schools should proliferate’.

And as for the future of Islam in India, the author makes bold to suggest that

‘Indian Muslims, given their role in the evolution of Islamic thinking, should take the lead in bearing responsibility for the future of their faith in partnership with the most populous Muslim country in the world, Indonesia.’

And where do the rest of us non-Muslim Indians fit into the scheme of things? Wahab does not cite him, but I would like to end this review with a quotation from Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi speaking in the Lok Sabha on May 3rd 1989:

“A secular India alone is an India that can survive. Perhaps an India that is not secular does not deserve to survive.”

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Op Sindoor 'new normal' against terror, will watch Pak actions: Modi Rajeev Deshpande

Life After Kohli, Rohit Lhendup G Bhutia

Bulls Stomp the Market on Calls for Ceasefire, US-China Trade Negotiations Moinak Mitra