Quarantine Diaries and Pastoral Accounts

It is hardly a surprise that not a lot of great art emerged out of the years of the Covid-19 pandemic. It was a time when people, across the world and its putative frontiers, were struggling to survive, when families had to contend with loss, and when our failure to invest in a functioning public healthcare system finally came home to roost. But what happens when art itself offers a mode of survival, a lifeline? I don’t mean the art that we consumed, often on screens, passively and out of sheer boredom, as we spent weeks and months confined to our homes. I mean art as a practice, a sustained and meaningful investment in craft and composition.

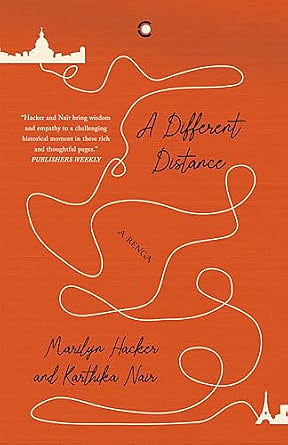

There are few poets more dedicated to the craft of composition today than Karthika Naïr, and few more poignant chroniclers of illness and grief are to be found working in any medium. Her latest collection of poems, A Different Distance, has sprung from a yearlong collaboration with another highly accomplished artist, several decades her senior, the American poet and translator Marilyn Hacker. At the start of the pandemic, a time of profound medical distress for Karthika, the two poets, both living in Paris, decided to form a pact with each other, one that held for an entire year, and has now resulted in the fragile treasure of this collection.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The poems are inspired by the Japanese renga, a chain linked form of poetry, where a word, image, or motif from the last line of a poem provides the impetus for the next one. The two poets went back and forth, writing a poem to each other almost every other day, for an entire year. The panic, fear, and general disorientation of the first days of the pandemic are evident in the early exchanges, as is the quiet tenacity with which both endured the abrupt change in their circumstances. I was living in Paris at almost the exact same time, and I could feel my heart clenching at their account of a city that had lost its bearings, and of a time which few of us are keen to revisit.

Unlike some of the more egregious “quarantine diaries” (Lëila Slimani’s rubbed many the wrong way), these poems do not dwell on idyllic hours spent in a country home, nor do they use the lockdown as a pretext for self-involved, solipsistic inquiries. Instead, they burn with the urgency of artists trying to make sense of a world adrift, and document the small, daily struggles that confront citizens from all walks of life. Both poets are also deeply engaged in the wider social and political stakes of the situation. Karthika talks about the heart-rending reverse migrations that many workers had to undertake in India, while Marilyn Hacker remains fully attuned to the series of disasters that struck Beirut (where she had been teaching) throughout that year.

It is perhaps ironic that Naïr’s previous collaborative effort, with the poet Sampoorna Chatterji, and artists Roshni Vyam and Joelle Jolivet, titled Over & Underground in Paris and Bombay is a celebration of cities and mobility. Cities and mobility are precisely the two things that were rendered off limits by the lockdown. There is no yearning here for the pastoral. Instead, for both poets, cities are the gardens from which they have been exiled (“Home becomes exile/ in the punished city”). It is what leads to the profusion of images of locked gardens and empty public spaces that occur throughout this beautiful, sombre, and always vital collection.

The pastoral is a more insistent presence in lone pine, the poet and educator Siddhartha Menon’s new book of verse. But his relation to the natural world, as attested to in these poems, is not romantic, but cognitive in character. Menon’s poetry is as interested in the interplay of the different elements that constitute the natural world—rays of light, ripples on the surface of water, birdcalls—as it is with the interplay of these elements with our modes of perception. One of the poems does quote an opening line from Keats (“Season of mist and mellow fruitfulness”), but the romantic option is broached only to be discarded (“sweep this too aside”).

Thus, a meeting of the glances produces several moments of drama at different points in the collection. In ‘Seeing becomes a poem’, three jackals freeze because “they saw you when you saw them”, while a nilgai stops in its track to return the poet’s gaze. Elsewhere, an owlet who first appeared as only “a smallness on the path” finds itself in a similar predicament;

“You look at one another.

It begins to sway its head from side to side

a rocking doll a stuffed cobra

an owlet. You are mesmerized.”

These encounters also serve as pretexts for the humour and sense of incongruity that characterise Menon’s writing. He has no qualms in referring to a group of orange flowers looming over a hedge as “shortlived / immodest twits”, or commenting on the odd asymmetry of the Amaltas tree, whose beautiful yellow flowers stand in contrast to its rough, uneven bark— “It is as if a blacksmith/were dripping lines of poetry”.

Many, if not most, of the poems in this collection were written in Banaras. ‘River Mornings’, a poetic sequence that appears early in the book, is a prolonged, secular paean to the complex, ever-changing, and embattled body of water that courses through the sacred city. It has little time for the “evening pieties” and “saffron glaze” that embellish the place. Instead, it documents the procession of forms and colours offered by the river with a sense of astonishment, even wonder. The poems favour an attitude of contemplation over veneration. But attention too is its own form of prayer.

More than anything else, I am grateful that Indian publishers continue to pay attention to the labour of poets. As a reader, I am immensely moved by the scope of their empathy and imagination, and by the finely discerning but capacious vision that emerges from their verse. There is much to be learned from their ways of looking at, and being in, the world.