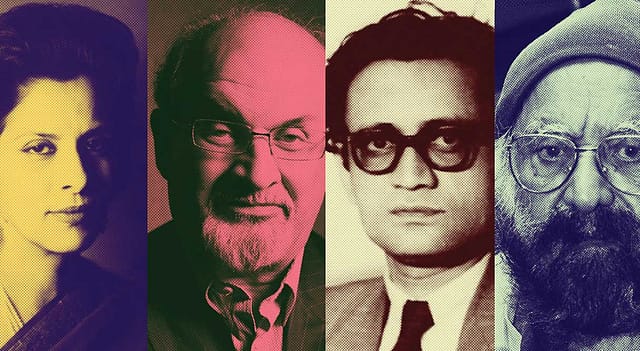

Portraits of Partition in Four Fictional Characters

Time enables forgetting. This amnesia can make rogues of citizens and clunks out of children. If we turn ignorant about how our countries have suffered and survived, if we forget what our grandparents and great-grandparents have witnessed and endured, we do injustice to our past, and turn willfully blind to the forces that define us. This is where fiction comes in. The novels and short stories set around Partition and the Independence movement force a remembering. These stories, spun from history, chronicle the blood-soaked origins of two countries, the depravity of it all, and the humanity that shone through. We choose four compelling characters from Partition literature to remind us of the turmoil of that time and the human struggle—lest we forget.

SUNLIGHT ON A BROKEN COLUMN

by Attia Hosain

LAILA

Laila, the orphan protagonist of Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961), is not the freedom fighter on the street. She raises no placards or slogans and does not brave the policeman's lathi or the mutineer's stone. But she is the freedom fighter in her home, in the city of Lucknow, as she pushes against the expectations and strictures imposed upon her, as she tries to find her own truth. She has the feistiness of Josephine March (Little Women) and the wit and eloquence of Elizabeth Bennet (Pride and Prejudice). But unlike them, she is also keenly attuned to the world outside her home and the churnings in her country.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

When we first meet Laila, it is the early 1930s and she is a 15-year-old in purdah who used to live in her grandfather's house and is now moving to her 'liberal but autocratic' uncle's home in Lucknow. Her fiery spirit and sense of justice are on display even as a teenager. Despite this, she is careful to ensure that she 'posed no problems of upbringing'. 'I was outwardly acquiescent,' she says. But like a country that had started to question and fight against the grip of its colonisers, Laila too evolves from outside acquiescence to full-blown rebellion over the course of the novel. She says, 'Inside me, however, a core of intolerance hardened against the hollowness of the ideas of progress and benevolence preached by my aunt and her companions. Rebellion began to feed upon my thoughts but found no outlet.' She realises that while she might have freedom of thought, freedom of action is harder to come by.

She rises to the defence of the 'menials' unafraid to take on the wrath of her aunts and uncles. Taken aback at her fearlessness, her aunt scolds her, 'Do you know what is wrong with you, Laila? All those books you read. You talk just like a book now, with no sense of reality.' She supports the Muslim girl in purdah who runs away with a Hindu boy, even though she knows that her elders think the 'wicked' girl only brought 'dishonour' and 'suffering' to the family. Laila says with passion, 'I am not defending wickedness. She wasn't a thief or murderess. After all, there have been heroines like her in novels and plays, and poems have been written about such love.'

From early on, Laila feels different from those around her and estranged from her milieu, because of her questioning spirit. She doesn't take concepts like 'wrong' and 'right' for granted. Instead she wonders what these categories mean in themselves. Unlike her friends who equate their futures with their husbands, Laila has other ambitions. She simply wants to 'go right round the world' and is surprised that others find her desire outlandish.

Even if she is not out on the streets, the happenings of the outside world infiltrate her home. The first signs of communal tension are sparked in Lucknow when the progress of a procession carrying a tazia is impeded by a peepul tree near a Hanumanji temple. The top of a tazia striking a branch of a tree, the blowing of a conch in the temple as the procession passes by, is enough to set off a riot.

When the first procession chanting 'Inquilab… Zindabad!' (Long Live Revolution) passes by her home, she marvels at the 'roaring tempest' in front of her and wonders at her own inaction.

If Attia Hosain does a remarkable job of fleshing out Laila's character, she also marvellously creates the ethos of Lucknow with all its tehzeeb. As 1947 approaches and matters come to boil, this way of life risks coming undone. And Laila realises this within the walls of her home. 'No one seemed to talk anymore; everyone argued, and not in the graceful tradition of our city where conversation was treated as a fine art… It was as if someone had sneaked in live ammunition among the fireworks. In the thrust and parry there was a desire to inflict wounds.' Ties that had kept families together for centuries were loosened beyond repair. And those who left for Pakistan would find it easier to travel the whole wide world than to visit the home which had once been theirs.

Married to her big love, despite the family's demurs, widowed and with a child, Laila is witness to the 'hate-blinded revengeful' mobs. But even at that time, not all her faith in humanity is lost. She asks an aunt, 'Do you know what 'responsibility' and 'duty' meant? To stop the murderous mob at any cost, even if it meant shooting people of their own religion'.

Sunlight on a Broken Column is one of those remarkable novels that create a movement in history through the story of a family. In Laila's bildungsroman, from a questioning teenager to a resolute 20-year- old, we see a nation itself coming of age.

MIDNIGHT'S CHILDREN

by Salman Rushdie

SALEEM SINAI

As the hands of the clock hit midnight on August 15th, 1947, whilst the monster roars in the street, and a dapper, sombre man intones: "Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny," a cucumber- nosed infant and another with knobbly knees enter the world, and are bestowed vastly divergent destinies by a nurse who swaps their name tags. As Salman Rushdie, their creator, explains, the children of midnight are only partially the offspring of their parents; they are also the children of the time, fathered by history. 'It can happen,' he insists, 'especially in a country which is itself a sort of dream.'

Saleem Sinai's tale in Midnight's Children (1981) unfolds some three decades before the child was actually born: from the blue Kashmiri sky that dripped into his grandfather's eyes and the perforated sheet through which his grandparents got to know each other, to the Agra house where his mother married a poet hidden in a basement and, later, another who gave her a new name and promised her a new life in Delhi, but where he lost his wealth to riots and perforce moved to Bombay where began the tick-tock of Mountbatten's countdown clock.

As his 32nd birthday approaches, and history pours out of his battered and disintegrating body, Saleem races against running-out-time to recount to Padma, his 'princess of dung', the saga of Midnight's Children. His is not merely the story of an individual with a peculiar nose; 'to know me,' he says, 'to understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.' For his misshapen nose gives him the ability to enter the hearts and minds of others, to know everything about everything; indeed, to believe that it was he who made things happen.

He is not the only one with a special gift, he soon realises. All children born in the first hour of independence were endowed with unusual powers: Shiva, his nemesis and 'twin', with extraordinary knees; Parvati, a lovely kind-hearted witch; a child who could step into mirrors; another whose words inflicted physical wounds; a time-traveller; an alchemist. Almost 600 of them scattered across the country, brought together in a cacophonic lok sabha in Saleem's head. Being the telepathic medium that enabled the Midnight Children's Conference to convene, Saleem is its natural leader, but slum-hardened Shiva is not one to easily relinquish premiership to a snotty rich kid, triggering a rivalry of knees and nose that would climax decades later.

Saleem's life will be 'the mirror of our own', the prime minister had prophesied in a letter to independent India's first born: indeed it is a metaphor for the destinies of his six hundred million compatriots.

The parliament in Saleem's head, though represented by magical children, cannot but be riven with the prejudices of their ancestors. Saleem ruminates that 'although we found it easy to be brilliant, we were always confused about being good'. Opinions on the purpose and principles of their fraternity are irreconcilable. Disintegration of the Conference is inevitable: it finally comes apart as the Chinese army spills over the Himalayas.

From sparking the riots that would lead to the break-up of the state of Bombay, to the shooting by a naval commander of his wife and her lover, from the disappearance of a holy lock of hair from the Hazratbal Mosque to the death of Nehru himself, Saleem sees his own hand. The 1965 Indo-Pakistan war happens because 'I dreamed Kashmir into the fantasies of our rulers,' and its hidden purpose is the annihilation of his family. Equally, he is responsible for the events of 1971 during which he finds himself in the ranks of the murderous Pakistan army striving in vain to retain its leash-hold on its eastern province.

Victory celebrations in Dacca fortuitously help Saleem re-establish contact with Parvati-the-witch who magically spirits him back to India. In a slum adjoining an historical mosque in Old Delhi, still clinging to the optimism-virus, he is reluctant to abandon his nation-saving project. But events lead inexorably to the declaration of a state of Emergency by the Widow. On June 25th, 1975, once again clock-hands join palms to signal 'the birth of a new India,' but this time 'the beginning of a continuous midnight which would not end for two long years'. At this moment too, is born his son—who is not truly his son; his destiny, like Saleem's, handcuffed to history.

Saleem conjectures that the truest, deepest motive for those stifled days of the Emergency is the Widow's fear of the potential of specially-endowed children born at a long- ago midnight hour, and her determination to eliminate them. When the bulldozers, accompanied by Saleem's alter ego—Shiva of the knees—decimate the slum adjoining the mosque and its inhabitants, it is to seize the principal of midnight's children and extract from him his secret.

Shrouded in his blanket of confinement, Saleem beseeches the indulgence of his cohort: 'Politics, children: at the best of times is a bad dirty business. We should have avoided it, I should never have dreamed of purpose, I am coming to the conclusion that privacy, the small individual lives of men, are preferable to all this inflated macrocosmic activity. But too late. Can't be helped. What can't be cured must be endured.'

TOBA TEK SINGH

by Saadat Hasan Manto

BISHAN SINGH

Toba Tek Singh (1955), an Urdu short story written by Saadat Hasan Manto, is one of the most iconic stories of Independence literature because it reveals the human cost of Partition in a few pages. With the lightest of touch, it spells out the arbitrariness of borders, the madness of it all and the tragedy of epic proportions.

The story is set a few years after 1947, in a lunatic asylum in Lahore. The governments of India and Pakistan decide to exchange their lunatics as they did their criminals. But in the asylum, news is limited and rumour and conjecture pass as fact. In the asylum, no one seems to know where Pakistan ends and where India begins and who should move where and why.

A Sikh called Bishan Singh, belonging to a village called Toba Tek Singh, has been confined to the asylum for 15 years. Though his name is Bishan Singh, he is called Toba Tek Singh. He often repeats a single line of gibberish, 'O, parh di girh girh di, annexe di bay dhayaan di moong di daal of the laaltain.' Rumour has it that in the last 15 years he has never lain down to rest and has abjured sleep altogether. His proclivities have disfigured his feet and reduced his legs to stumps. He looks wild, but is known to be harmless. He had once been a zamindar in Toba Tek Singh but suddenly lost his mind and was abandoned by his family in the asylum.

He asks people where his village is, but no one seems to know. Manto writes, 'Those who tried to explain themselves got bogged down in another enigma: Sialkot, which used to be in India, now was in Pakistan. At this rate, it seemed as if Lahore, which was now in Pakistan, would slide over to India. Perhaps the whole of India might become Pakistan. It was all so confusing! And who could say if both India and Pakistan might not entirely disappear from the face of the earth one day?'

When it is Bishan Singh's turn to be relocated, a guard tells him that Toba Tek Singh is in Pakistan, but once he crosses, the Pakistani guards try to push him across the line to India. He is then told that his village is in India, but he refuses to be persuaded.

'Just before sunrise, Bishan Singh let out a horrible scream. As everybody rushed towards him, the man who had stood erect on his legs for fifteen years, now pitched face- forward on to the ground. On one side, behind barbed wire, stood together the lunatics of India and on the other side, behind more barbed wire, stood the lunatics of Pakistan. In between, on a bit of earth which had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.'

Toba Tek Singh's timelessness as a short story has been ensured because it reminds us that it wasn't just the 'insane' who could make no sense of Partition and the mass migration of people from one side to another. Partition made homes alien and turned neighbours into murderers. Neither in India nor in Pakistan, but only in the earth of no name could Bishan Singh finally find rest.

TRAIN TO PAKISTAN

by Khushwant Singh

JUGGUT SINGH

Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan (1956), set in the fictional village of Mano Majra close to the Sutlej River, is not a novel that a reader can forget easily. With clinical precision, it plots the craze for revenge, the creation of a mob and the humdrum nature of violence. Reading it is it to relive the breaking apart of a country and to reckon with the possibility that if this violence happened 70 years ago, it can just as easily be repeated again.

Mano Majra is a tiny village. It has only three brick buildings and a cluster of flat-roofed mud huts. Seventy families live here, an equal number of Sikh and Muslim families and only one Hindu family. The Sikhs are landowners and the Muslims, tenants. Time in the village is set by the passing of the trains. The mail train rushing to Lahore and blowing its horn is the wake-up alarm for villagers. When the evening passenger service from Lahore comes in, they lock their cattle up for the night.

One of the lead characters in the novel is Juggut Singh aka Jugga. A 'bad character' known as 'the most violent man in the district', he must report himself to the police station once every week. The son of dacoit Alam Singh who was hanged, he is feared by all for his bull-like strength and Goliath-like height. If we see him in the throes of lust at the start of the novel, a chapter later we see him pulverise an enemy through the bars of his prison. He is a man of passion, who knows nothing of moderation. His liaison with a Muslim weaver's daughter Nooran keeps him invested in staying on in Mano Majra.

Jugga is accused of carrying out a dacoity against his own village folk. When he's asked if he killed Ram Lal, he replies, 'Toba, toba! Kill my own village bania? Babuji, who kills a hen which lays eggs? Besides, Ram Lal gave me money to pay lawyers when my father was in jail. I would not act like a bastard.'

Train to Pakistan shows how the relationships and codes which bind humans and create civilisations are upended in times of conflict. The trains no longer just mark time, but they become harbingers of doom that come packed with corpses. The homes that have been evacuated are quickly pillaged by those who said they'd look after them. Villagers who had wept over the departure of Muslim friends volunteer to avenge the death of Sikhs. The Sutlej river strains at its banks and becomes a watery grave for the scores who have been massacred upstream.

When he is released from confinement, Jugga's only concern is if and where he can find Nooran. Despite the horrors inflicted on his village, Jugga has an odd fatalism, 'They cannot escape from God. No one can escape from God,' he says. As the novel chugs towards a thrilling climax, it is Jugga the 'badmash' who proves that even when the blood-dimmed tide is loosed, there are those with the conviction and will to do the right thing.