Poet of the Paradoxical City

My metro pass, I lent her. She went

wherever her whim sent her.

Back home at night she held me tight,

said ‘You never told me, you fool,

that y’ll are this damn cool,

‘Violet’ and ‘Pink’ and ‘Magenta’?

The DMRC has a Lesbian Agenda!’

— ‘Sappho in Delhi’

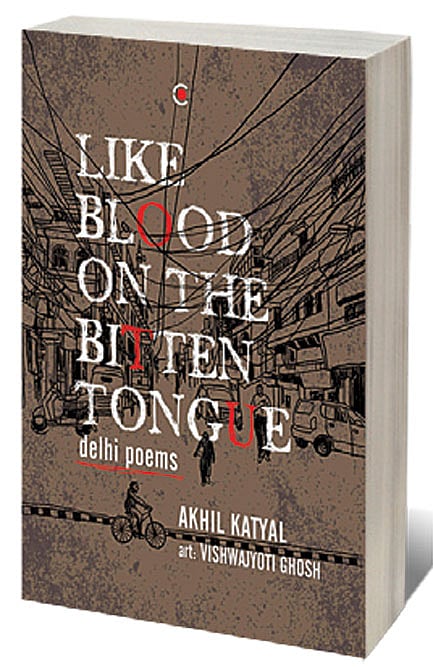

AKHIL KATYAL’S POETRY rings with two distinct registers: irreverent and solemn. In some poems, he lends his Delhi Metro card to the Archaic Greek poet Sappho and chats with first-time auto drivers, and in others, he remembers untimely deaths in the country’s recent past. Incongruous as such a fusion may seem, both relay memorable stories, both record the present incarnation of Katyal’s geography. His latest collection, Like Blood on the Bitten Tongue: Delhi Poems (Context; pages 162; Rs 499), is accompanied by Vishwajyoti Ghosh’s art which adds an element of grit to these poems. Ghosh’s sketches of Delhi are grainy and saturated with inextricable urban details like security guards, electrical lines, police barricades and cycle rickshaws. Katyal’s poems too are often located in the streets, in the public places where humans are surrounded by history, extant social oppressions and moments of serendipity.

Like Blood on the Bitten Tongue pays homage to the Delhi of pedestrians, cyclists and riders of public transport. The introduction of the metro in the early 2000s with subsequent expansions changed the way residents experienced the sprawling city. Katyal’s Delhi reflects that access and movement. It is a portrayal many present-day inhabitants will find familiar. Among other places, the reader is brought along to the oldest burning grounds in the city, a central university, markets, monuments, a museum. Instead of illustrating these poems in a literal sense, Ghosh has constructed his own version of the city replete with images such as a pollution mask, a government ID card and a rendering of a question that has been asked repeatedly since 2016, ‘Where is Najeeb?’

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

“Delhi is crazily unequal, power-hungry and smog-crazed,” says Katyal, “but in other ways, it is also maddeningly beautiful.” On the one hand, the city has “the dangerous pomposity of North Block and South Block, power unseated by people, undone by power again and ugly, bombastic Modi posters laced with propaganda”. On the other hand, it holds “the bravery of Shaheen Bagh, Seelampur and Hauz Rani, the sheer hope and strength of (Chandrashekhar) Azad on the steps of Jama Masjid, langar lines of Bangla Sahi and spring in Nizamuddin”. He acknowledges that every Delhi story must kneel in the face of the pollution crisis—there is a pressing need for a public narrative that puts this issue at the forefront of our understanding of the city. The image that comes closest in Katyal’s mind to the hypnotic hold Delhi has on people is a question raised in an Agha Shahid Ali poem, ‘Can you rinse away the city that lasts / like blood on the bitten tongue?’

Katyal moved from Lucknow in 2003 to pursue a BA in Delhi. It was the first time that his plans for himself departed from his family’s designs for him. In a family of engineers, he chose literature. In these classrooms, he found stable assumptions about gender, sexuality and caste challenged. At every new place he lived and worked at—PG accommodation in Kamla Nagar, barsati in Indra Vihar as a young professor, Shiv Nadar University in Greater Noida, rented apartment in Jangpura extension—he kept walking and exploring. He encountered parks, naalas, dargahs and malls with indoor canals and gondoliers. Like Nicole Kidman (playing Virginia Woolf)said in The Hours (2002), he cherishes the violent jolt of the city, not the anaesthetic sense of the suburbs.

Perhaps most poignantly, the city has returned Katyal’s linguistic inheritance to him. All four of his grandparents who came from Jhang-Maghian, Sargodha, Sheikhupura and Lahore in what is now Punjab, Pakistan, wrote and spoke fluently in Urdu. But because independent India paid scant attention to Urdu in its syllabi and schools, the script skipped a generation in his family. Three years ago, a former student named Abdur Rehman Khan taught Katyal the script through six crisp lessons he prepared for him—slowly caressing the written words into sense. “It was not like learning something new,” he says, “It was like remembering what was forgotten.”

He can now read news tickers, street-signs, headlines, book titles, poetry couplets: “Each of those moments are little parties in my head.” He resists the easy and common exoticisation of Urdu. The cloudy appreciation of vague shapes and curves has been replaced by a recognition of the letters as “ordinary, regular, like any language, like any letters that commonly spell ordinary, regular words like ‘tum, main, kahan, ab, aur’ [‘you, me, where, now, and’, respectively]”. He points out that the sounds of Urdu have always been his. In northern parts of the subcontinent, those who know Hindi also know Urdu and vice versa. The two languages are inseparable from one another. “They are shadows of each other, Siamese twins, mildly, even beautifully distorted mirror images of each other, not overlapping entirely but sharing substantially.” Katyal says, “No one speaks Doordarshan Hindi in any case or bookish Urdu. No one says, ‘Mere hriday mein ye vichaar aaya hai.’ Everyone says, ‘Mere dil mein ye khayaal aaya hai.’” What is spoken in Jhang and Lahore and what is spoken in Delhi and Lucknow is recognisable to each other. “They are all my places, our places,” he gently suggests, “give or take a Partition or two.”

When I first interviewed him in 2015, he was writing feverishly and sharing his poems compulsively online. Five years later, he’s slowed down, thanks to the wise counsel of friends and the schedule of a public university. “Some poems still sneak out,” he says, “some come from a more considered place. Other cheeky little numbers just roll off.” As long as he is able to keep writing both sorts, he remains satisfied. As a poet with a wider audience than most, his counsel to aspiring writers on navigating audience is simple and measured: “Write what you think must be written. Sometimes write as if a reader doesn’t exist. At other times, as if you want to hold the reader in your arms and tell them something urgent, as if your life depends on this ability to tell. Realise that research is not a bad word in poetry. Read up on what you’re writing, don’t just rely on your ‘feelings’.”

Many of the poems in the collection draw from recent events such as the Nirbhaya protests, the murder of Hafiz Junaid and the Maruti workers’ strike. “Poems are little offerings to big moments,” he says. Though unassuming on their own, he finds that when the words are right, the emotions sincere and the rhythm infectious, a poem can end up giving one courage. Referring to Aamir Aziz’s poem ‘Main Inkaar Karta Hoon’ written and often recited during the ongoing protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, he says, “His voice is indefatigable, mellifluous, brave. His eyes are sure with the knowledge that he is saying what needs to be said today, in the teeth of things. Whether you hear him online or in person, that act of listening makes you carry on, makes you step out.”

The power of a good poem, he reasons, lies in giving people the sense of being understood. He urges people to listen to Sabika Abbas Naqvi’s ‘Mera Desh Jal Raha Hai’ (which is as acerbic as it is funny), Hussain Haidry’s momentous ‘Hindustani Musalman’ and punch-in- the-gut ‘Chhipkali’, and Varun Grover’s ‘Hum Kaagaz Nahin Dikhayenge’, which has now become anthem-like. “They all achieve the potential of a good poem. They are offshoots of a crazed moment, they mark it, they are blessed by it. They anoint it. And, in turn become its archive.” Katyal’s poems themselves are suitable companions in this age of “waiting for bad to get worse/ for it to get better.”