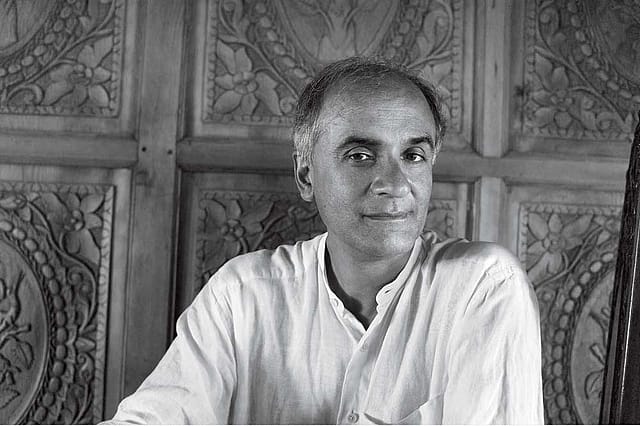

Pico Iyer: Writer of the Heart

I FEEL I KNOW Pico Iyer. Even though I have never met him. But that is the thing with Iyer, his readers believe he is a friend. To read his books is to return to Earth with a keener eye and sharper mind. One marvels at the latticework of sunlight, the shatter of leaves below one’s feet, at the fragility of petals—because he has drawn our attention to them. With ten works of non-fiction, and two novels behind him, he is the Leonard Cohen of travel writing, having created his own genre, the travel rumination. The action in his books isn’t about goings and comings, rather it is about actively seeing and being fully absorbed in the here and now. In his writings he might transport you to Sidney and Saigon, Beirut and Honolulu, but in all these places he doesn’t go looking for the exotic, instead he invests in how seasons pass, and time closes. He isn’t the writer you turn to for itineraries or must-dos, you choose him to help you unpack your inner and outer life.

He still travels the world and spends plenty time in California (where his mother stays) but Japan is home. In his latest book Autumn Light; Season of Fire and Farewells (Viking; Rs599; pages 236) Iyer returns to some of his favourite themes; the joy of less, of quiet, of what’s fleeting.

The book opens with his wife Hiroko’s phone call from Japan (he’s in Florida) telling him about her father’s ailing health. The death of a family member, the change of the seasons, the scatter of one’s children, the thrills of ping-pong, in many ways that is all Autumn Light is about. At the end of the book Hiroko asks him what kind of book he’s writing, and if anything actually happens in it. To which he replies, ‘Well, not exactly nothing. But what happens is not so visible. It’s hard to see which parts are important until years later. Or maybe never.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In an email interview from the US, Iyer writes that he has spent 16 years on this book of little over 200 pages. He invested this time, “taking out sentences and dramas and distractions to try to create something as clear and resonant as an empty room”. No wonder this book reads like memoir honed into haiku.

In 1991, Iyer published The Lady and the Monk: Four seasons in Kyoto, which mapped his early impressions of Japan, as he made his foray into Zen Buddhism. Here he would meet Sachiko, mother of two children, wife of a typical Japanese ‘salaryman’, who would end up cementing his relationship with Japan, for life. Autumn Light is not quite the sequel to The Lady and the Monk as they differ in tone and temper. The Lady... has all the bluster and brio of finding love in a new city. Autumn Light, on the other hand, is seeped in the sepia tranquillity of familiar places and people who are one’s own.

But read together they give us Japan. It is a Japan which is as much a Tomorrowland, the apex of modernity, as it is an ancient culture thick with water spirits, and eight million gods of rice and wind, maple tree and sky.

I ask Iyer about his relationship with The Lady... today and he says, “When I re-read it now, a part of me cringes at the smart-aleck know-it-all, barely out of his twenties, passing such sweeping and ignorant judgements on everything he sees. But another part, admires that boy’s freshness and daring, and understands that he, on first viewing Japan, can see things that a long-time resident has long forgotten.” He adds, “That the outsider can offer perspectives a local has long ago forsaken—has been the theme of all my writing.”

Iyer sees in his previous books “mementoes of spring and a person I could never be (and never need to be) again.” But he also believes, and the subject of Autumn Light is: in “certain fundamental ways, the child of eight is always visible in the grandparent of 80.”

The Pico Iyer of Autumn Light is more rooted, and happier. The older Iyer, compared to the younger one, can reckon with the fact that everything one loves is ephemeral, just like the cherry blossoms, which lavish its blooms only for a few weeks. He adds, “Both books consciously embrace a Japanese—which is to say wistful and even unresolved—ending, but in the first book I feel I was a Western visitor slowly moving towards Japan. After 31 more years there, I hope I can write a little more as someone with a Japanese family, community and neighbourhood.”

The Japan that Iyer gives us might be rooted in poetry and philosophy, but it comes to us from a place of emotion rather than analysis. He explains his disdain for the word ‘intellectual’, “Ideas, the intellect, come between us and the world, and in my writing I have worked quite hard to try to give us a world unmediated: in this book, for example, a Japan not seen through a screen, not seen through explanations, not seen through ideas, but seen through and with the heart.”

Iyer, the child of two professors of philosophy who studied the religious traditions of the world, would often come home from school to find monks at his parent’s home in Oxford in the 60s. His parents introduced him to the scriptures and religious texts, while his English schools trained him in Anglicanism.

He has travelled with His Holiness the Dalai Lama for over 40 years, and has written a book on him The Open Road (2009). In the Dalai Lama, Iyer sees that while he can deliver speeches of “extraordinary depth” it is his human touch—“the right gesture in the here and now”—and kind presence that is his greatest teaching. Iyer says, “Of course, the texts he reads and recites daily have taught him a huge amount, much as Proust and Melville and Emily Dickinson have taught me. But what moves me in watching him—and what I’d like to begin to learn—is how to leave all that and extend a helping hand.”

Iyer himself spends months at a monastery. This engagement and absorption with ‘higher matters’ so to speak, endows him with a rare charm and humility. He is the author who in his writings stretches out a helping hand to his readers.

THE LEITMOTIF OF Autumn Light is the passing of time. In the acknowledgments the ‘first presence’ Iyer gives thanks to is his ‘lifelong adversary and boss, Time,’ for allowing him for over 16 years, to sift through experiences and feelings, and for revealing which mattered, and which mattered less. Iyer admits to seeing time as a deity of sorts, and that’s why he chooses to capitalise it in special instances in Autumn Light and The Lady... When required he capitalises ‘nature’, and ‘fate’ and ‘god’, and must prevail against the whims of copy- editors who try to reduce it to lower case! Time is best heeded through the passing of seasons. And in Japan he has found that the seasons are observed much as a religion elsewhere. He says, “The awareness of passing time stands at the heart of the culture. And to capitalise time is to remind oneself of how small—as well as mortal—one will always remain.”

Today the fear of dying warps much of modern society. In Autumn Light by writing of impermanence, Iyer makes us reckon with ‘being mortal’. As he travels between East and West, he sees the contrast in cultures play out. In California, the promise that we can turn back the years is harped upon. Silicon Valley is packed with engineers and scientists who believe that we can live longer and better than we ever have. But this misplaced optimism can be crippling. Iyer asserts, “This ‘blue sky thinking’ leaves us helpless in the dark, so I admire a seasoned old society—such as Japan—which is defined less by the pursuit of happiness than by an unsparing awareness of reality.”

Autumn Light pivots on this awareness that all things must die. Autumn, Iyer has learned, isn’t the season that teaches us how to die, rather autumn dispenses a much harder challenge ‘of learning how to watch everyone you care for die.’

Today, Iyer is fabled for his life shorn of distractions. He has never used a cell phone. He stays clear of social media (though he can now be found on Twitter). His wife and he have lived in a two-room flat for 26 years. “We have no means of transportation other than our feet,” he says, “and no television I can understand.” He doesn’t take his “stripped- down” way of life for granted and knows most people have responsibilities that they cannot avoid, but 30 years ago he made the conscious choice to give up a glamorous job in New York, for the back lanes of Kyoto. And it is a decision he doesn’t regret.

The surrender and rejection of worldly goods also brings with it a paring down of language. He describes the prose of The Lady... as “crowded and maximalist and digressive, as full of noise and colour as a Bollywood stage set”, in comparison the language and ambience of Autumn Light is a Basho poem. By saying less, rather than saying more, like Basho, Autumn Light makes one alive to the beauty of the world and the smallness of man against the drama of nature.

In the three decades that he has spent in Japan, Iyer has come to appreciate “the great Japanese language known as silence.” Words can divide and conceal, whereas silence can unite and heal. He says, “Words can’t catch feelings, which is why the writer’s job is to push as close as possible to silence, and beyond.” In a new book that will release this September titled A Beginner’s Guide to Japan he will include a whole section on words, followed by a section on no words. He has studied the importance of silence since the autumn of 1992, when he first moved to Japan. At that time he wrote, ‘Words are what we use for small-talk, gossip, diversion; silence is what we can happily share with those we truly trust and love.’ This is a maxim he still stands by and has found that Japanese people by tending to speak as little as possible, “maintain a deep sense of harmony, and even community.”

Given the quicksilver quality of the words, what is role of the writer, I ask. Iyer says, “The job of the writer has always been to get into the shoes, the skin, the soul of someone radically different from oneself, and to see the world he thinks he knows from the other side of the street.” Quoting the novelist George Saunders, who he calls one of the most brilliant and visionary writers of today, he adds, “‘The other is just us on another day.’”