Notes of Misadventure

A young woman, dressed in dramatic red and yellow robes and with an eye painted in the middle of her forehead, is stretched out in the camel pose. She’s flanked by four women—with an electric guitar, bass guitar, drums, and a keyboard—their faces covered in Chhau-style masks. To the sudden sound of crashing cymbals, the yogini stands up straight, raises her arm to the sky and screeches loudly. Striking feral poses at each beat, she does a kind of war dance, as her band mates begin to sing in a menacing growl.

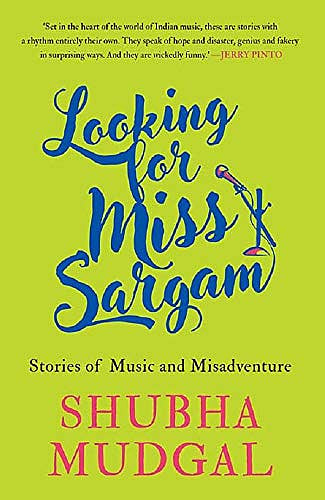

Even before the video ends, Sandeep Solapurkar, a senior employee at the country’s oldest, much reputed record label, has walked out of the meeting room. The Badass Bandariyas are too much to take for the man who has singlehandedly developed a magnificent classic music catalogue for the label. The vivid, chucklesome passage forms the crux of A Farewell to Music, one of the seven short stories in Shubha Mudgal’s Looking for Miss Sargam.

The singer’s fictional debut—she’s written music columns in Hindi and English for a long time—gives us a ringside view into the Hindustani classical music world. Wielding wry humour to narrate the stories and misadventures of harmonium players, singers, and music teachers, Mudgal delivers a subtle yet authentic comment on an industry fighting to retain its authenticity and essence in the face of rising commercialisation.

In Aman Bol, the vice president of a major media company pulls off a coup to bring together an Indian and a Pakistani artiste together on stage, not without the customary clash of egos. In the highly entertaining tale, Mudgal casually references the state of the media—‘it was no longer just ad space that was on offer; you could now buy a story, a column, a feature or any activity you wished to indulge in, even if it was nose-picking in public or picking fluff from your lover’s navel.’ Or how producers and composers would rather rope in winners of reality shows to dub their songs than pay a dubbing fee.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

We meet Asavari Apte, a sweet-tempered vocalist and teacher from Pune who longs to bag an international tour, in Foreign Returned. She’s rightfully apprehensive too—a fellow vocalist had to sing alaaps for a fashion show in St Petersburg, where models sashayed in lingerie and leather boots. While finally on tour in the States, Apte, much to her horror, is offered a chance to judge a DJ competition at a Holi Utsav, with a video reference from the previous year where a DJ croons, ‘Say Raddey Raddey baybee, and you will get Nirrvaner; Say Krishna Krishna baybee, you’re sure to find Anannder.’

Mudgal does a stellar job of bringing out the good nature and naiveté of her characters, highlighting problems of copyright infringement, missed credits, moral dilemmas and power dynamics. Perhaps the most poignant story is the eponymously titled Manzoor Rehmati, on the harmonium player from a small town in Uttar Pradesh who yearns for a Padma Shri. Singer Shivendra Kumar Jha, in At the Feet of His Master, reminds his collaborators, electronic music duo Gabbar n Mak, to give him due credit—even Bijli and Chamki, their cats were credited in their last album, while he wasn’t.

Flitting in and out of the stories are memories of the elusive Miss Sargam—a pop singer in a three-piece suit who could sing in both male and female voices—who has now all but disappeared, having returned to her first love, classical music. Mudgal’s writing is self-assured, sardonic and wonderfully observant—‘aap na, cum-po-jeeshun par concentrate karo,’ says Mrs Saxena to her husband in Taan Kaptan—lending an additional layer of authenticity to her characters. Looking for Miss Sargam is equal parts heart-warming and heartbreaking, establishing Mudgal as a storyteller with great flair.