Mystery Begum

For decades, a three-member family claiming to be nawabi royalty lived in a secluded Delhi forest and captivated audiences around the globe. Were they beleaguered nobility or deluded fakesters? Begum Wilayat Mahal, a woman tracing her descent from the house of Awadh, arrived at New Delhi station in 1975, with her young children Sakina and Ali Raza. She demanded that the Central government recognise her claims and give her back several ancestral properties snatched by the British when the kingdom was taken over in 1856. After spending a decade living in the waiting room of the railway station, the family was awarded

Malcha Mahal, a run-down former hunting lodge in the heart of the capital.

Here the imperious, striking begum and her children lived hermetic lives with a handful of servants and several dogs. They occasionally invited foreign journalists for interviews. Glamorous former royals and a feral jungle existence? The newspaper stories practically wrote themselves.

In 2019, the New York Times ran what appeared to be the definitive story on the family—Wilayat was no royal, just an ordinary widow who had tried to reinvent herself in the face of familial and national rupture. By then, all three were dead—the last surviving member and the only one the reporter met, Ali Raza, died in 2017 after a suspected illness. A long-running mystery seemed to have finally drawn to a close. But had it really?

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

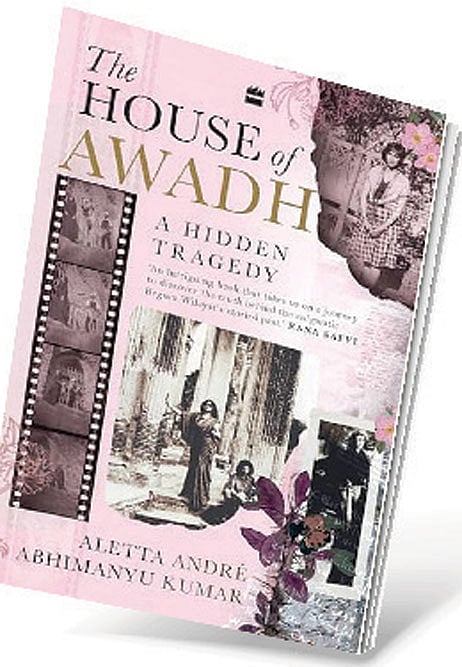

The House of Awadh: A Hidden Tragedy by Aletta André and Abhimanyu Kumar revisits all the evidence, and then some, to arrive at a different conclusion. André, a Dutch historian and journalist, and Kumar, a poet and writer, have thrown themselves into shoe-leather reporting with zeal. They track down obscure figures, visit forgotten hamlets and dredge up musty records across Delhi, Lucknow, Karachi and Kashmir. No lead is left loose, no theory unexplored. The narrative unfolds as a journey of discovery—few definitive claims are made in an omniscient third-person voice. The book emerges with new findings about the family, tracing their lives in Pakistan and Kashmir, before they arrived in the capital.

But this is not just a fascinating historical puzzle. It is also an opportunity to get a palimpsestic glimpse of India. “The more we came to know, the more it seemed as if the family’s history was tied to the story of India itself—from British rule to Partition, post-Independence nation-building, identity politics and the rise of Hindu nationalism,” they write in the introduction. The main thread of the begum’s story is told against the backdrop of the Kashmir problem, sectarianism within Islam and the decline of India’s aristocracy.

The book jettisons the simple binary framing of whether the family’s claims were real or fake to ask bigger questions. What is history? What is memory? Does madness preclude claims to truth? “Different memories, even when contradictory and unverified, are equally valuable parts of this story,” they write at the end. “They all contribute to the truth.”

However, The House of Awadh is let down by the writing. Too often we see the cardinal journalistic sin of putting dry facts into the mouths of interviewees instead of paraphrasing (“We are six in total: four sisters and two brothers”). At other times, detailed descriptions of each meeting, or bland quotes add little (“It used to be quiet in the mornings, like it is today on a Sunday” or “She also told the media to not harass them”), while the occasional thesis-like tone does not help (“Most of the information…has already been summarized and does not necessitate a repetition”). More skilful editing could have trimmed the bloating and digressions.