Monkey Business

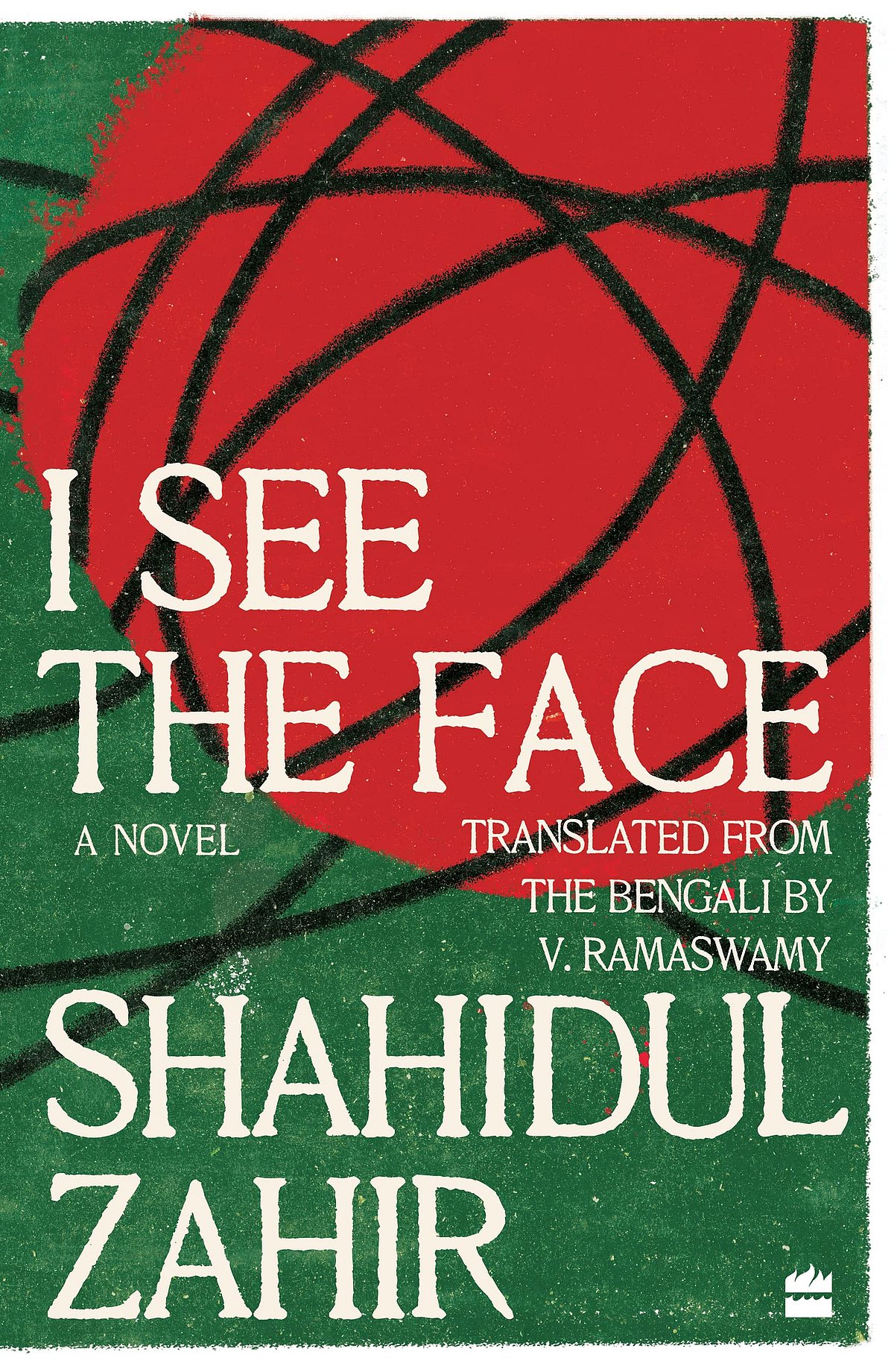

Bangladeshi novelist and short story writer Shahidul Zahir’s novel, I See the Face interweaves the lives of two boys from Dhaka’s Ghost Lane. While one boy was nourished by monkey’s milk as an infant, the other accidentally gets smuggled to another part of the country and is buried inside a truck full of sawdust.

Set against the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, with a milieu of characters entering and exiting the scene, at times all at once, the story of I See the Face rests upon the uncertain young shoulders of these two adolescent boys—Chan Miya and Mamun Miya—who grew up in the same para (neighbourhood) but went on to have entirely different identities and prospects.

Chan Miya has spent most of his childhood living with a rather belittling sobriquet of “Monkey Boy” and “Bundle Boy”, and who despite his unfortunate origins went to study in an English-medium school. He was the one who fared well, recited all the English rhymes, stood out as a favourite student in the eyes of the British teacher, but in due course cascaded into the pit of thieving and debauchery. A fatherless, colour-blind boy, Chan Miya, who got bullied and mocked by his classmates into quitting his studies had to embrace an impoverished life that was predestined for him.

Mamun Miya, or Rabbit, on the other hand, who despite being born into a comparatively better-off family than Chan Miya’s, ends up with an identity crisis. After being discarded from the smuggled truck in Chittagong, he ends up in the home of a young girl named Asmantara Hoore Jannat who keeps him as her human pet. So, he remains captive inside a cage, curled up in a circle, for a good part of his adult life before he is set free.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Strung together with a series of “perhaps” and semicolons, Zahir’s plot switches between the past and present. It is almost as if the events are playing out in one still timeline, while everything else is rushing past in many different timelines.

Readers of fiction would easily identify elements of magic realism woven into the socio-political reality of Bangladesh but what is praiseworthy is the author’s expertise in retaining the Bangladeshi spirit and tone.

The war, however, acts more like a catalyst to the story than a central theme, which allows Bangladesh’s regional context and the idiosyncrasies of its people to shine through. Therefore, at the heart of the novel is the everyday chatter of the lives of the common people, their worries and struggles in tow.

Zahir’s voice never gets morbid, at any point, even when the Pakistani Razakars come knocking on the door of Khoimon who, at the time heavily pregnant with Chan Miya in her belly, rebukes them with her unabashedly rude comebacks. Her interjections with Mrs Zobeida Rahman too are amusing. The two women, like their respective sons, grew up in the same neighbourhood disliking each other inherently from the time they were young school-going girls, and their attempt at surviving the war forms an integral part of the social, cultural, and economic fabric of Bangladesh.

Kolkata-based V Ramaswamy does a flawless job in translating Zahir’s Bangla to English, as he did with the two novels of the Chandal Jibon trilogy by Manoranjan Byapari (The Runaway Boy and The Nemesis). His (and perhaps the editor’s) decision to retain a generous occurrence of Zahir’s original Bangla phrases is a treat for those who understand and appreciate the sound of the language.

Zahir’s book must be read not just with open eyes but an open mind and heart; perhaps it will all make sense or perhaps it will not; it will however stay with the reader and Zahir will be remembered as an original and lasting voice in contemporary Bangla fiction.