Memories of a Different Country

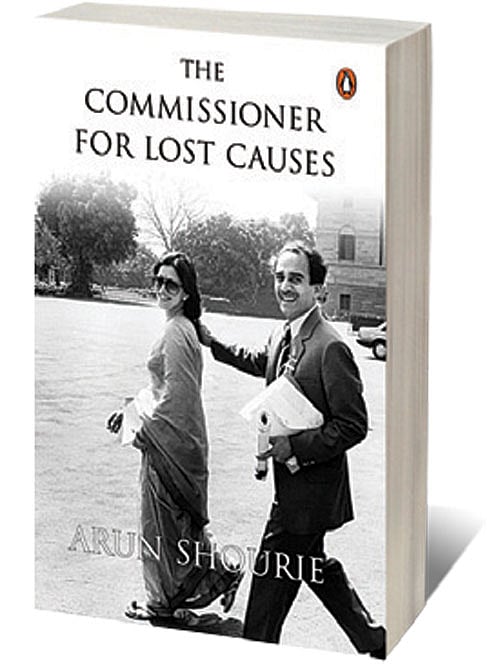

THE QUESTION THAT poses itself as you make your way through Arun Shourie’s memoir, The Commissioner For Lost Causes, of his days as a journalist—and the decided superstar he was in the 1980s, face of the fantastic stories of The Indian Express ranging from purchasing a girl and exposing slavery to bringing down a chief minister for corruption—is how come he has missed the social media revolution altogether? Why isn’t he part of an arena that makes old media irrelevant every time the hand moves on a clock? It is not for Shourie not being suited for it. His humour is as sharp as any pen he has ever held—a late example, the coinage of BJP as “Congress plus cow”—and in the hands of someone with public standing that is a weapon of amplification. The stock of anecdotes he carries of the wielders of power in India is extensive, and when has a good storyteller ever wanted for an audience even on Twitter? What explains the disinterest?

From the present book, even if not a sole factor, you can make one hypothesis and that is his fixation with making a case as detailed as possible. Even for newspapers that was onerous, and, much against prevailing norms, it was something he brought into journalism here in the late 1970s, after returning from the US where he worked at the World Bank, and being co-opted on top into The Indian Express by its maverick owner Ramnath Goenka. Shourie writes in the book: “There were several things about the paper that were crying out to be changed, and as my new colleagues and I attempted to change them, Ramnathji was the one person who supported us…There must be no limit to the length of the stories.” Social media abhors length. The narrative of public discourse happens at the surface now because the technology’s primary objective is attention grabbing. Shourie’s route, page after page of copious references for each argument, is as much an anachronism as traditional journalism itself is becoming. Everyone is a journalist now because opinions, millions of common little bits joined through by hashtags, retweets and likes, shape the fact.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

If the book did what most memoirs do, limiting it to human encounters and observations, it would be a page turner. As when he is telling the story of how The Indian Express bought Kamla, a woman, for ₹ 2,300 after investigative reporter Ashwini Sarin spent months building contacts in Madhya Pradesh border where the trade was happening. It is a disturbing story because while the public good is evident, it is an ethical quagmire, not conscionable from Kamla’s point of view. “So widespread must the trade in women have been that, at times, Kamla thought her fate to be the normal one: Ashwini’s wife told reporters that Kamla asked her how much Ashwini had paid for her, Uma; that as Ashwini had already paid for her, Kamla, why could the two of them not stay together with him,” writes Shourie. She eventually disappeared from the shelter home that had become her residence after being thrust involuntarily into the national limelight.

There are many riveting portraits, especially of Ramnath Goenka, who made The Indian Express what it became and then got jealous after Shourie began to be identified more with the paper. He runs through the book like a shadow, a newspaper proprietor who couldn’t help think that he must also decide how the country was run, an itch that would often be for the good and sometimes for the bad. As when he led a resistance against Indira Gandhi during the Emergency, and at the weakest moment, marshalled an opposition, one which saw Shourie becoming acquainted with him. Or, for an example of his overreach, there is the story of Goenka joining hands with Giani Zail Singh, the then president, to plot the sacking of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, that Shourie opposed and did his best to scuttle. In personal relations, Goenka brought the same cunning and chaos. When Shourie couldn’t get along with editor S Mulgaokar, Goenka told him: “Tum ussey ladtey kyon ho? Mujhey dekho. Mulgaokar meraa mulazim hai. Par jab main uskey ghar pahunchtaa hoon, pehley main Mulgaokar ko salaam kartaa hoon. Phir main uskey kuttey ko salaam kartaa hoon— ‘Kuttaaji, meraa salaam.’ Poocho kyon? Kyon ki mujhey Mulgaokar se kaam karvaanaa hai, aur kutta Mulgaokar ko pyaaraa hai ...(Why do you quarrel with him? Look at me. Mulgaokar is my employee. But when I reach his house, first I salute Mulgaokar. Then I salute his dog—‘Mr Dog, my salutations.’ Ask me why. Because I have to get Mulgaokar to do some work, and the dog is dear to him . . .)”

If the Emergency made Shourie, then it also left him permanently allied against the Congress, and in a country where there was mostly one-party rule, that was not the most comfortable of corners. He clearly relished it and found his calling there. It also meant that he ventured into areas that others shied away from, like criticising the judiciary. In the book, there is a scathing deconstruction of one of India’s most venerated Supreme Court judges, PN Bhagwati, using a judgment where he deliberately allowed for more control of the executive over transfer of judges. Shourie methodically takes the judge’s earlier judgments to show how Bhagwati, whenever he felt like, was a strict Constitutionalist who went by the exact meaning of its word, and at other times a liberal interpreter who decided what the word of the Constitution meant. His readiness to reduce the power of the judiciary in the case is hinted at him not getting along with the chief justice of the time. And that is topped by the reproduction in its entirety of a flattering letter by Bhagwati to Indira Gandhi after she returns to power that includes lines like these—“I am sure that with your iron will and firm determination, uncanny insight and dynamic vision, great administrative capacity and vast experience, overwhelming love and affection of the people and above all a heart which is identified with the misery of the poor and the weak, you will be able to steer the ship of the nation safely to its cherished goal and the glorious vision of the founding fathers of the Constitution will become a living reality.”

It wasn’t the government alone that Shourie maneuvered against, sometimes it was his superiors, as when editor BG Verghese, in keeping with Goenka’s wishes, refused to publish a story about a missing government file that Shourie had traced. He leaked it to Parliament forcing its publication. In between, he writes a letter to Verghese saying why he should not be listening to Goenka for Goenka’s good and copies that letter to Goenka himself. It would be an invitation to be sacked, which is what happened eventually but a few years later Goenka brought him back into the saddle.

There is a section in the book in which Shourie sets the ethics and tactics for journalists. It is an idealist position, some of which his own career shows the difficulty of adhering to, like not getting too close to the people you might have to write about. But the vanishing of norms is not the storm that revised the landscape he was such a figurehead of. It is in how the reader metamorphosed. Crores of Indians now think of news anchors presenting one-sided news/opinion as the word of final truth. Earlier, politicians needed media to interface with the public, now they talk directly to people who in an earlier age might not even have been consumers of media or politically opinionated. It is the aftermath of a lost world, not just lost causes.