Mapping the Hindu Mind

VINAYAK CHATURVEDI, it is palpably clear, has set himself a brief—ie to read VD Savarkar outside of the binaries of hagiographical or synographical accounts that exalt or demonise him. He distances himself from settled assumptions and controversies that surround Savarkar. It may be said that the author exercises strategic restraint and moderates his own normative principles in response to public attitudes and political agendas, in order to enhance the legitimacy of his account of Savarkar.

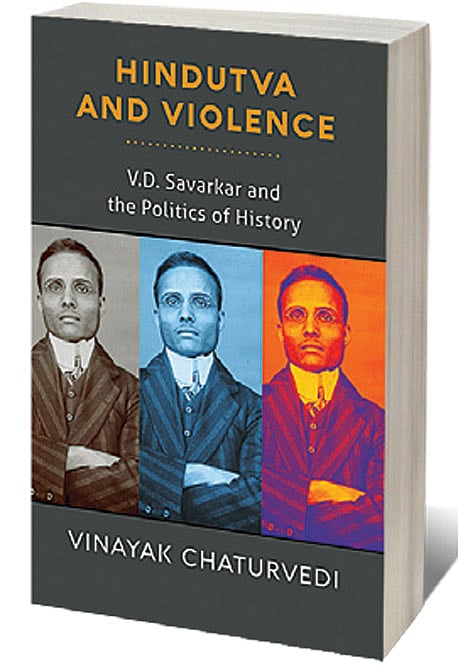

Historical facts are always aplenty and diverse enough to offer selections and to lend themselves to appropriation and misrepresentation if you have a political agenda of proving or disproving a particular thesis. It is to the credit of Chaturvedi, the author of Hindutva and Violence that the choices he makes are not what might be called “bad faith selections”. He’s neither taking the utterances or texts of Savarkar as indicative of “real intent” and “actual politics” (a wilful error made by at least one recent work on Savarkar); nor is he keen to perpetuate or dispute claims that relate to Savarkar being veer, swatantra-veer, patriot, martyr, coward, British loyalist and so on. Chaturvedi wants to steer clear of these preoccupations, quite simply because those are not his questions. He has instead, as he puts it, “a straightforward proposition”: “I try to make it thinkable that Savarkar contributed to political thought”. For him, “disagreement requires engagement, not peremptory or condescending dismissal”. The author therefore sets out to read Savarkar outside of the moulds he had been cast in.

There is no doubt that this is a meticulous work of research and a lesson in how to ‘read’ history outside of the tribulations and temptations of contemporary politics. One can even discern an empathy that the author brings to this reading. For instance, by proposing that Savarkar was “engaged with Humanist thought and ideas which he had first articulated in his book on Mazzini”; or, in suggesting that in Savarkar’s Essentials of Hindutva we find reflections on “Mimansa— epistemology, ontology and philosophy more generally”; or, in describing Savarkar’s writing through adjectives like polemical, repetitive, euphemistic, dramatic, melodramatic, vivid, formal but never as vituperative or vengeful. The issue really is not whether Savarkar deserves that empathy. Perhaps he does for the tribulations, suffering and sacrifice he underwent, his own mercy petitions, vengeful politics notwithstanding. The issue really is whether that empathy is “critical”. In what follows, I highlight inter-related themes that I find under-interrogated in the book, which makes it fall short of its “critical” potential.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A KEY THEME OF the book is that Savarkar is writing a “History in full”. Chaturvedi persuasively argues that the bifurcation between an early “Revolutionary Savarkar” and a later “Hindutva Savarkar” is overstated. He finds continuities, but not in locating traces of Hindutva in earlier writings. Rather than locate genealogies of Hindutva in utterances of Bhai Parmanand or in Savarkar’s post facto claims, Chaturvedi suggests that a more revealing thread is the theme of “history in the full,” which first makes an appearance in Savarkar’s The Indian War of Independence (1909), and is a precursor for his later works like Essentials of Hindutva (1923) and Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History (1971).

History-in-full is basically a history that includes the “chief actors”, their “countless actions”, “their motives, their inspirations and their desires”. It includes, as Savarkar puts it, “… all the department of thoughts and activity of the whole Being of our Hindu race.” These “departments” include stories from the epic traditions and mythologies, as well as uncorroborated assertions and aphorisms “to substantiate his interpretation of Hindutva”. Chaturvedi terms this approach, “conjecture as method”. He says that “for Savarkar there existed systems of knowledge that could dispense with absolute reliance on research.” This is a bit puzzling, but according to Chaturvedi, this constituted a “critique of Orientalist formation” that did not straightforwardly fit within existing and available frameworks.

Chaturvedi stops here. He stops short of interrogating this idea of “history in full” which derived its “fullness” from perceptions, fictions, stories, unfacts, unreason that attached themselves to fragments of truths and history. A further and an obvious question that the book doesn’t ask is: does dispensing with reason and valorisation of Hindu identity, masculinity and bravado in “glorious epochs”, by itself constitute a challenge to Orientalist frames and to a recovery of “Bhartiya” decolonial consciousness?

Decoloniality is a way for us to re-assert the knowledge that has been side-lined, forgotten or discredited by the forces of modernity, settler-colonialism and Orientalist narratives. However, it is not a means to concoct, or to erase the distinction between fact and fiction, myth and history or, importantly, ignore the ethical advances of the modern era. Dispensing with rational arguments is dangerous manipulation. Any deflection from reason and evidence is an attempt to mobilise irrational and unconscious processes.

What would have added to the book’s fairness-claim, is an acknowledgement that Savarkar’s “history in full’ is an ideology that aims to stir up affect and fantasies about Self and “others”, pasts and futures, bodies and boundaries for political outcomes of a deeply divisive kind. Its purpose was not so much to challenge the colonial construct of “racial inferiority” of Indians or to disrupt colonial logic and the seeming “naturalness” of racial imperialism. But rather to construct and crystallise a Hindu identity in opposition to the Muslim one.

Savarkar’s historical claims had a purpose. A pedantic question that every social scientist must ask is “to what purpose”? With what intent? To what purpose was this methodological tool of “conjecture as history” deployed? If indeed it was, as Chaturvedi also acknowledges, to justify violence and the exclusion of Muslims as valid, authentic, deserving citizens of this country, then the idea of history-in full needs to be unpacked and interrogated for what it was a propaganda device. As an account, “history in full” should aspire to restore, elevate, renew and validate the multiplicity and plurality of lives, life-experiences, culture and histories. If it does not do so, it serves to ask of “history in full”—which and whose history does it actually represent? And which and whose future is being crafted through those ostensible histories.

As someone who has recently written a political biography of her own grandfather Competing Nationalisms: The Sacred and Political Life of Jagat Narain Lal, (A Hindu nationalist and a freedom fighter), I appreciate “restrain as an approach” where the aim is to neither indict nor exalt but let a fair textual reading speak for itself.

But restraint is a carefully calibrated approach. While theorists need to moderate their normative principles in order to enhance the fairness-quotient of their account, they need to be vigilant enough to not forsake it. Calibration requires honing the standards of judgement rather than dispensing it. In his anxiety to steer clear of political ping-pong, Chaturvedi ends up presenting a meticulous but benign account of Savarkar that is detached not only from the politics of these times, but also the politics of those times. Savarkar’s thought appears untethered from its intent, as well as from its own contextuality and teleology. In making his own reading apolitical, Chaturvedi actually ends up making Savarkar apolitical.

All thinkers are not political leaders. Savarkar was. Thought, conceptual repertoire, questions of “epistemology, ontology and philosophy” that Chaturvedi highlights, are as much aspects of Savarkar’s political action and therefore have to be weighed not just for their epistemic content, but also their political content. While there are mentions, brief discussions about the exclusive and often violent nature of Savarkar’s Hindutva, the book refrains from providing analytical insights into the perverse relationship between religion, politics and violence in Savarkar’s thought. Was Savarkar right in justifying a deliberately partial version of history? Was his history-in-full really ‘full’ and complete? As a reader, one would have liked to get a sense of that.