Lives Less Lived

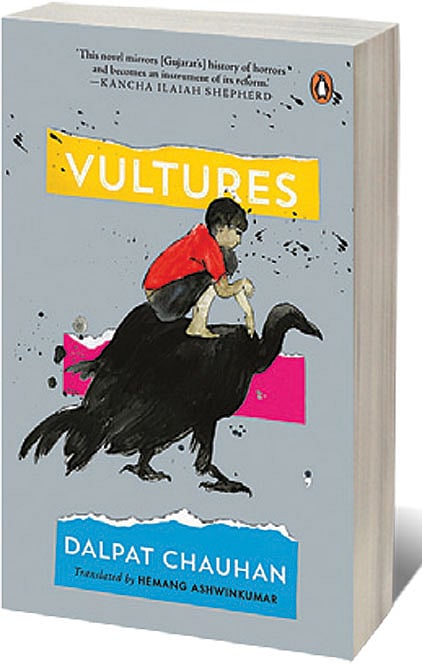

THE BLURB ON the jacket of Dalpat Chauhan’s Vultures (translated by Hemang Ashwinkumar) is shocking. It takes you straight to the heart of the story, which tells of the murder of a Dalit boy by upper-caste men in Gujarat in 1964. But what’s more shocking is how things haven’t radically changed even now. Of course, there are laws to safeguard the rights of Dalits. However, the reality often reeks. The “brutal sword of caste patriarchy”, as the blurb says, still swings wildly in many parts of India.

It’s a well-known fact that casteism and violence go hand-in-hand. A character, towards the end of Vultures, laments about the higher status accorded to animals that are able to get in and out of lakes as they please. But he isn’t even given that small amount of freedom because of his caste. His very touch is considered impure by the people who make—and break—the rules. Although the novel is set more than half a century ago, its timelessness is a cause for concern. Iso, the protagonist, is born into a family of tanners, and he works for Mavaji as a serf. His days and nights get emptied out by backbreaking work for which he’s paid little.

Shanoji, who’s yet another serf, also works for Mavaji, but since he resides above Iso on the caste ladder, he’s given a longer rope. Chauhan paints a compelling picture at every juncture. In some places, he describes the lanes that are divided by castes, and in others, he brings in dogs and vultures to indicate the chaos that unfolds. The sky, likewise, becomes a part of this landscape whenever his tale takes a turn for better or worse.

Iso, like Mavaji’s daughter Diwali, is just a teenager. Shouldn’t teenagers be out playing in the sun? Ah, that happens only in a fair world. Through the course of the book, nothing about Vultures ever screams fair.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

There is, instead, simply a shadow of infatuation that envelops the two. It’s natural for young folk to feel attracted to each other. In fact, sexual curiosity can be taken as a positive sign. But Iso knows the kind of punishment he’ll be given if he eyes Diwali.

Diwali, too, while making advances, looks around to confirm if she’s alone with Iso. She’s too afraid to talk to him more than necessary in the presence of her family members. And Iso, therefore, reflects a similar behavioural pattern. Vultures is not a love story where Iso learns to run a step ahead of his enemies. He doesn’t want to fight for her, or do anything that’ll put his life in danger. His thoughts don’t go that far, either. He’s happy with exchanging little flirtatious one-liners as and when a sly opportunity arises.

Somewhere along the course of the novel, there’s a great section where Chauhan points out the steps involved in skinning a buffalo and the varied ways in which all the people from different castes come together to staple their desires on the delicious cuts that’ll be made available to them. I thought this was the juiciest portion of Vultures, but when the same scene plays out in a dreadful manner much later, I gasped. This magnetic relationship between animals and men finally felt like a nightmare.

And while Chauhan leaves no stone unturned to capture the village’s unwritten codes, he unwittingly turns Diwali into a one-dimensional character. He exclusively focuses on her physical features and builds her existence around a teenager’s fantasy. She never comes across as a fully functional person who harbours dreams of her own. Nevertheless, Vultures is an important novel that discusses issues that are still relevant today.