Life’s Longing for Itself

IT CAN BE hard to pinpoint what a novel is about when the writer is as talented as Saskya Jain, weaving together multiple strands of history and fiction to produce a book so complex and stunning that you want to re-read it immediately after you have completed your first reading.

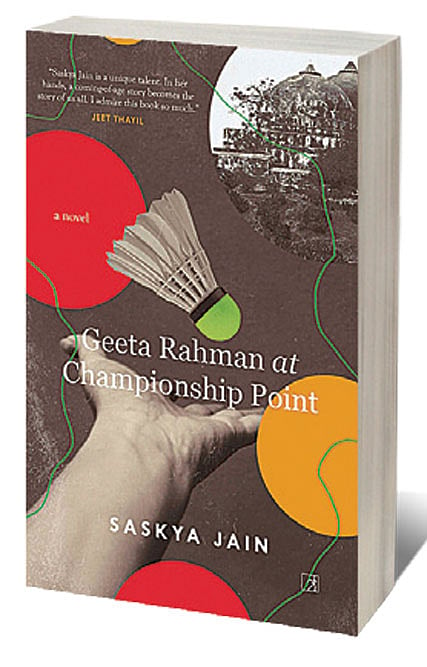

Jain’s latest novel Geeta Rahman at Championship Point tells the story of a 12-year-old badminton player named Geeta, born to a Hindu-Muslim couple. Her mother Sakshi is dead, and her father Akbar is raising her with the help of Anu aka Naniji. Sport and religion are two of the major themes that drive the plot, which leads to a heartbreaking end that cannot be revealed here because that would take away from the author’s slow and masterly build-up.

Geeta’s best friend is a boy named Faraz, slightly older than her. They love to play badminton in Kaka Nagar, Delhi, the neighbourhood that is not only their home but their entire universe. Geeta and Faraz are like siblings to each other even though their fathers hardly get along. Saleem, Faraz’s father, is a cop. He loves his son but is afraid that the boy might fall into bad company or pick up habits that would land him in trouble some day.

What could be more troubling for the father of a teenage son than the prospect of a budding romance between a Muslim boy and a Hindu girl? The novel, after all, is set against the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, and the Bombay riots of 1992-1993. These events play a decisive role in the lives of Jain’s characters, particularly Faraz and his beloved Sitara who is the manga-loving daughter of Kaka Nagar’s newest residents Vicky and Anjana.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Vicky, like Akbar, is a civil servant. The other thing that they have in common is their concern about Geeta’s future. While Akbar believes that badminton will not provide a stable career path, Vicky is of the opinion that Geeta has the potential to be a champion and must allow him to coach her. The face-off between these adults has been sensitively portrayed. Geeta seeks the approval of both, as they try to realise their unfulfilled dreams through her.

Sitara used to love badminton but she has stopped playing because she does not want to be her father’s pet project. Vicky imagines that his approach to fatherhood is different from that of his own father, Prakash, who is now dead. However, Vicky is repeating the same mistakes.

Prakash was not a good listener; neither is Vicky. Both are excessively sure of themselves. They end up alienating their children as good intentions do not always translate into skilful actions.

It is too late by the time Akbar, Saleem and Vicky sit down to introspect. They should have read Kahlil Gibran’s poem ‘On Children’ where he writes, “Your children are not your children. / They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.” Years after losing Sakshi to cancer, Anu too wonders if she had been a good mother. Benita aka Bird Aunty, who is Geeta and Sitara’s neighbour, thinks that motherhood is “one of humanity’s biggest PR hoaxes.” She prefers to look after injured avian babies rather than human children.

Jain’s book is a fine piece of work—political without being shrill, emotional without being all over the place. Her characters are not difficult to empathise with. Even their harsh, somewhat questionable choices, seem to come from a place of hurt, a longing to be understood. They dig their heels in but there are forces beyond their control.