Life As a Gallery

MANJU KAPUR FAMOUSLY began her literary career late in life. Her first novel, Difficult Daughters (1998), was published when she was close to 50, and it ended up winning a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize (best first book, Europe and South Asia). Since then, novels like A Married Woman (2003), Custody (2011) and Brothers (2016) have established her as one of the quietly brilliant voices of today’s Indian English literature. Style and structure-wise her books are a throwback to the grand old 19th century novels of Austen and Dickens; multi-generational dramas featuring interlinked sets of families. Kapur’s elegant, multi-clause sentences go about their business efficiently, with grace and compassion. Her great subject is the inner lives of women. As they negotiate the personal and professional cul-de-sacs that come with being a woman in India, Kapur’s women make difficult choices and through the course of these books, learn to live with the consequences.

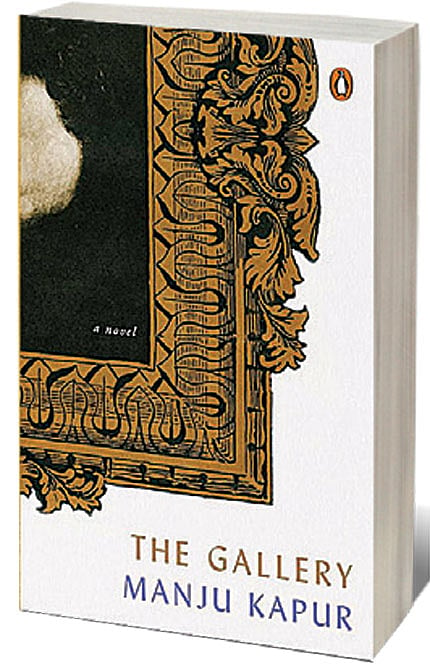

Her recently released seventh novel, The Gallery (Vintage; 336 pages; `599), adds to this rich oeuvre and is arguably 75-year-old Kapur’s finest work yet. Minal Sahni, wife to successful lawyer Anuj Sahni and mother to Ellora, decides to operate an art gallery out of a garage at their picturesque Golf Links house. At around the same time, Krisna, one of Anuj’s Nepali employees at work convinces the couple to hire his wife Maitrye/Matti as a live-in help for Ellora. Soon, Matti’s own infant daughter Tashi is growing up alongside Ellora, although their parents belong to very different worlds.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

As we move across the novel at a sedate yet addictive pace, the trajectories of these women’s lives chafe against barriers of gender and class. The role of marriage and the patriarchy, the socio-economic capital bestowed upon a woman through ‘respectability politics’, women re-evaluating their marriages in middle-age — these are some of the story’s recurring themes. And as we see Minal’s business expanding through the 1990s and the 2000s, we also see a de facto history of Delhi’s consumerist culture emerging, especially, in the second half of the novel.

At a recent interview at her Delhi residence, Kapur speaks about setting the narrative in the art world. Clearly, Minal was supposed to find herself through entrepreneurship, and the art world presents several angles to suit this narrative purpose.

“I go to the India Art Fair every year, it’s my one little foray into art,” Kapur says with a chuckle. “And I’ve always been interested in galleries. What struck me about this world was that most of these people were women. A lot of galleries started off in homes, garages and basements and it’s one of the reasons I picked the art world as the setting [for the novel]. Timewise and in several other ways, this world is less rigid than a lot of others. The elasticity of this world was also, therefore, a factor. How do you straddle the public and the private, the professional and the personal?”

Art is a business like any other, yes, and so it involves the requisite amount of mercantile conduct. But at the same time the product here is something people feel strongly about at an emotional level: the enterprise contains abstract value and meaning for the stakeholders involved, it offers them something other than money, too.

“There’s also a moment in the book where Minal tells Matti/ Maitrye that she has been working for decades now,” Kapur says, “that she has enough money for herself and her child. And it’s not just about the money, I feel. It’s also that the degree to which she depended upon her husband in the past influenced the way she thinks. She has now travelled to different parts of the world, met and done business with different kinds of people. All of this builds her self-esteem in a way that she hadn’t known before.”

Kapur takes a subtle, carefully calibrated approach to writing men. Often these are characters whose behaviour and ideologies end up causing harm, directly or indirectly, to the women in their lives. And yet, these men are not presented as pantomime villains, or served up to satisfy the reader’s bloodlust, so to speak. There is an internal logic to their behaviour pattern, but they are not glorified or lionised. Kapur simply presents us with the circumstances and conditioning that has led to them becoming the way they are. Alok, Minal’s husband in The Gallery, is another classic example. Within the constraints of his upper-class existence in Delhi, he is a “reasonable” man, if largely disinterested in caretaking/nurturing, housekeeping or other ‘feminine-coded’ behaviours. He is even generous, after a fashion, but even this redeeming trait manifests itself in the transactional, mercantile way often associated with the upper classes in Delhi. He is initially supportive of his wife’s new business but does not understand the workings of it — he goes about offering “discounts” to people at Minal’s gallery events, much to her chagrin. He agrees to pay the lion’s share of Tashi’s hospital bills when the child is ill, but only after working out the math properly and informing her father Krisna that a certain amount will be deducted from his monthly salary for the next three-four years.

“Right from the beginning there’s a difference between the way Minal and Anuj think about people,” Kapur says. “He’s not an unkind man, he’s simply a product of his upbringing and social settings. He pays, for example, for Tashi’s surgery but he believes divisions between people should be in place. He doesn’t believe anything ought to be handed out to people for free. Whereas for her, these are the people she lives with, works with, she’s emotionally invested in these people. And when they are in need, she can’t be sitting around doing the math!”

There’s a great little passage in the book at around the 50-page mark, where we see Minal allowing Matti/Maitrye to keep her own child (Tashi) alongside Ellora for much of the day. We are told that all household staff have been instructed to hide the extent of this coexistence from Alok, because of his innate belief in the “divisions between people” as Kapur puts it.

“Minal’s audience, depending upon who they were, thought that either she was taking things too far, just like her, or that she was being impractical, just like her. First no maid, then bend over backwards to accommodate maid and child. Between employer and employee was a tacit understanding that Alok not be exposed to these adjustments. When he was around, he hardly saw Tashi. She was kept in the kitchen with Radheshyam, and as soon as Krisna was back Matti disappeared upstairs, returning baby-less.”

The first half of the novel keeps its laser-focus on Minal and her personal/professional adventures, contrasting them with the arduous weeks and months spent by Matti. In a similar vein, the novel’s second half concentrates on their two children and how their physical proximity is in sharp contrast to their impending futures. Near the hundred-page mark there’s a superb passage that gives away the novel’s architecture—it’s like both aforementioned narrative strands are presented side by side, much like an artist’s body of work in one of Minal’s exhibitions. In this passage we see three generations of women, each making their peace with their circumstances. But the endpoint at which their ‘compromises’ are made are different in each generation—progress is incremental and necessarily so, the novel seems to suggest.

“For a moment Matti turned away her head to hide the pain that had never vanished; how badly she had wanted to go to school, how quickly she had learnt to keep silent about this yearning, for her mother would then curse her father for dying and throwing them on the mercy of a family too small-minded to consider a brother’s daughter worthy of education. Tashi would never know what it was like to be left out of a whole possible future. Compared to that, what were the little ways in which she was left out, nothing. Being excluded from Ell’s social circle, being treated as an honorary toy to be picked up when needed, discarded when other toys came along, all nothing.”

That last bit about Tashi feeling ill at ease within Ellora’s social circle is revelatory. It shows us the vast advantages that the children of the wealthy have in India. Basically, if you have college-educated parents, you have a comfortable head start in life, a gap that’s never really bridged. Kapur’s characters here often find themselves thinking in terms of destiny or fate but on the odd occasion they also think about, say, affirmative action or reservations in higher education. Minal once parrots her college classmates’ nebulous line about “merit” being sacrosanct. But by the end of the same chapter, Minal is the beneficiary of women’s reservation at a university, forcing her to rethink the role of affirmative action. Kapur is a novelist who has thought long and hard about education, especially women’s education in India. Having taught English at Delhi’s Miranda House for decades, Kapur saw firsthand how command over the language was one of the drivers of class divisions among young people—it was also the source of major professional and social advantages.

“I’d see it all the time when I was teaching English,” Kapur says. “In India it’s such a class marker from day one. I would see so many students who were smart, aspirational, who wanted to achieve something in life. But their English held them back; they didn’t come from English-speaking backgrounds. The thing about art is that there’s no language required — if you are a talented artist, you can make it. Sure, there are resources and backing required here too but the entryway isn’t as daunting as it is with learning English.”

By the time The Gallery winds up you feel like you know each person within its 340-odd pages; such is Kapur’s skill at characterisation and pacing. And the product arrives after year upon year of grafting, chipping away at the extraneous bits. In an era of fast turnarounds and a novel-every-year-like-clockwork professionals, Kapur is an old-school writer who sits with her drafts for extended periods of time, taking several years to complete each project—another trait that sets her apart from her peers and establishes her uniqueness within Indian English literature.

“When I write things come to me very slowly—it’s one of the reasons why I do it every day, little by little,” Kapur says. “I can add layers of complexity every day, but I can’t tell you how the story is going to end from the beginning. It’s why I write so many drafts—my next novel is currently on its eighth draft and it’s still nowhere near the final form I would like to see it in.”