Leave Agatha Christie Alone

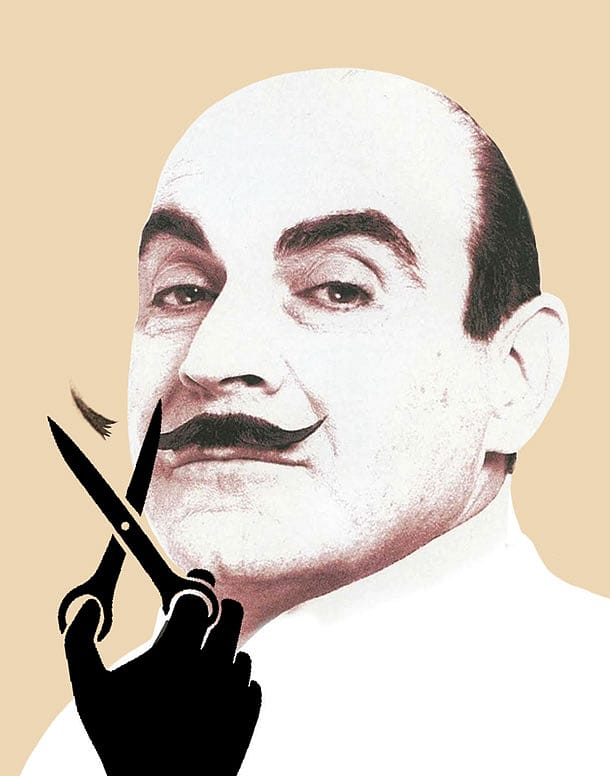

DEMOCRACIES HAVE always prided themselves on allowing their citizens free speech and their writers the freedom to write what they please. But in recent years, publishers in the UK and the US have used sensitivity readers to highlight and remove 'offensive' references to gender and race. So what should we do about racist and sexist slurs in beloved books from an earlier era? Well, publishers have already 'corrected' some words in books by Ian Fleming and Roald Dahl. It is now Agatha Christie's turn.

Christie wrote in the heyday of British colonialism and during the dismantling of the empire, two World Wars and the flower power of the 1960s. It is not surprising, then, that the characters in her books espouse the less palatable sentiments of a national, racial and class superiority, as well as a hankering for a bygone era when everyone knew their place in the world. Moves are underway to sanitise her books, ones authorised by her great grandson James Prichard who runs Agatha Christie Limited. Behold some of the changes in the new editions of her classics.

In the Miss Marple short stories "local" has replaced "native", a servant described as "black" and "grinning" is now "nodding", with no reference to his race. Miss Marple's musings on the staff in A Caribbean Mystery (1964) as having such "lovely white teeth" has been removed, as has a judge's "Indian temper", and the description of a black woman's torso as "black marble". "Oriental" as in "Zeropoulous spread out a pair of oriental hands" (Death in the Air, 1935) has been cut out too.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In Poirot's first outing in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), his description of another character as "a Jew, of course," has been removed. And in the same book, a young woman with a "gypsy style" becomes simply "a young woman". Some of these changes, though, dilute Christie's craft. She had the knack of describing a character's personality using just a couple of adjectives or a telling detail. "Gypsy style" conjures a free spirit while "a young woman" doesn't tell us anything about her personality.

A similar objection can be made to other changes. A character (Mrs Allerton) in the 1937 Poirot novel Death on the Nile complains that a group of children are pestering her: "they come back and stare, and stare, and their eyes are simply disgusting, and so are their noses, and I don't believe I really like children". The new version is: "They come back and stare, and stare. And I don't believe I really like children." For a reader, the disgusting eyes and noses conjure up the scene from Mrs Allerton's insular point of view. Those words were chosen by Christie to create a particular effect namely Mrs Allerton's disgust of the "foreign". "Stare and stare" doesn't quite do it to the same degree.

In her all-time bestseller though, the racist slur is printed in the title, Ten Little N******. This was renamed, And Then There Were None, in 1977, and the N word in the children's nursery rhyme in the book became "soldier". A Christie fan (I include myself) would not have problems with that change because it does not erode the flavour of the book. Removing such an egregiously racist word may be justified on grounds that the word was not central to that story, but others ask, where will it all end? If you change one word here because it is offensive to a race, and one word there because it is offensive to a sex, then what of words that anger a religion, caste, class, language, tribe, generation, ideology and so on? The removal of "ugly" and "fat" from Roald Dahl's books is an apt example.

In an article entitled, 'Be Careful When Censoring Speech,' Barry Wood points out that in the 1890s, the New York Public Library removed Huckleberry Finn from its children's reading room not because of the 'N' word (which occurs 200 times in the book) but because Huck "scratched" when he itched and because Twain used the word "sweat" instead of "perspiration". When asked for comment, Twain said publicity over the incident would sell more books, and he was right—20 million copies in over 50 languages, and still counting.

AN EVEN MORE compelling argument to not change Christie's works is this: good crime fiction often reflects the terrors and anxieties of a society at a particular time. Christie, her great-grandson says, set each story in the year she wrote it, and so became a voice for the social history of that time. Her best works were written in the period between the two World Wars, a time of war mongering and economic woes, when ethnic stereotyping and racism along with the fear of the foreigner was the norm. Not surprisingly, her characters reflect these attitudes.

For instance, in Murder in Mesopotamia (1935), the narrator (an English nurse) who has come to Iraq for the first time describes the workman at the archaeological dig. "You never saw such a lot of scarecrows—all in long petticoats, and their heads tied up as though they had toothache." Later in the book, the nurse describes a suspicious Iraqi as having a "dirty yellow colour". Of course, these views are racist. The nurse is viewing the Iraqis as a racial group, different and inferior to hers. But that's her attitude—she creates a caricature of the Iraqi—which Christie captures in these words. Sanitising the words would change the character of this particular type of an Englishwoman, and reduce the complexities in the story.

In the slice of social history Christie writes from, one where British society closed ranks against the foreigners either because of the looming World War or because of the waves of migration from the colonies. In the inter-war period, these foreigners were usually white —from 'wild' regions of Europe (The Secret of Chimneys, 1925) or South America (Cards on the Table, 1936). The most famous foreigner, of course, is her master detective, Hercule Poirot, a Belgian policeman-refugee.

When we come to her books written in the 1950s and '60s, a period of decolonisation and migration from the colonies to England, the anxieties of the decaying upper-middle classes (Christie's lot symbolised in Miss Marple), revolve around the "native" foreigners and even more around the concern that class distinctions are no longer preserved and the young "offbeat" generation are a complete cipher to their parents. Christie's books reflect these concerns. In The Pale Horse (1961), a young woman is described as smelling of "perspiration-soaked wool" and "unwashed hair". "The girls looked, as girls always did look to me nowadays, dirty." The narrator, a middle-aged historian of all things Mogul, contrasts this picture with "Indian women with their beautifully coiled black hair, and their saris of pure bright colours hanging in graceful folds, and the rhythmic sway of their bodies as they walked." Today, the Indian woman's description would be pilloried as being orientalist, and in the current climate, the language can be seen as offensive to the youth. But these were the prevailing attitudes of that time, and by modernising Christie's books, we lose a key feature of her books, the slice of social history she captures so deftly in her characterisations.

In fact, as an author, Christie had the ability to step outside her class and country and view British parochialism with amusement. This is most apparent in the encounters between the son of the English soil Inspector Japp and Poirot. Poirot's fondness for offering sirop and hot chocolate instead of a manly beer or whisky is often the butt of jokes by an affectionately contemptuous Japp. And Poirot knows how he is perceived and often plays up those traits, while also getting a dig in about English idiosyncrasies.

If the Queen of Crime's fiction can be 'corrected' then the next on the chopping block will be the father of the English detective story. There are many racist references in the Sherlock Holmes stories written by Conan Doyle in the late 19th century. The Sign of the Four (1890) tops the list with Tonga, the villain's henchman, who is from the Andaman Islands. The Andaman people are described as "naturally hideous, having large misshapen heads" and the people of India are described as little black devils and fiends. Holmes himself is a misogynist: "Women are never to be entirely trusted— not the best of them." Those were the prevailing attitudes in the late Victorian era, and are faithfully portrayed by Conan Doyle.

The debate over sanitising texts boils down to the question: can modern readers be trusted to make their own choices? I think they can. As Mark Twain, who was dismissive of censorship, said: "Censorship is telling a man he can't have a steak just because a baby can't chew it." By all means include a warning in the preface for modern readers, but let our beloved texts be.