KR Meera: Write and Subvert

OVER THE LAST DECADE KR Meera has become one of the most recognised Indian authors, whose work comes to English readers from the original Malayalam. Since the publication of her novel Aarachaar (Hangwoman, 2012), she has become synonymous with a fiction that punches the gut. Her books—whether they are short stories Yellow Is the Colour of Longing or a novella And Slowly Forgetting that Tree or her previous novel Jezebel (2022)—tell of embattled women, their hardships, which bend them out of shape, and ultimately their resilience.

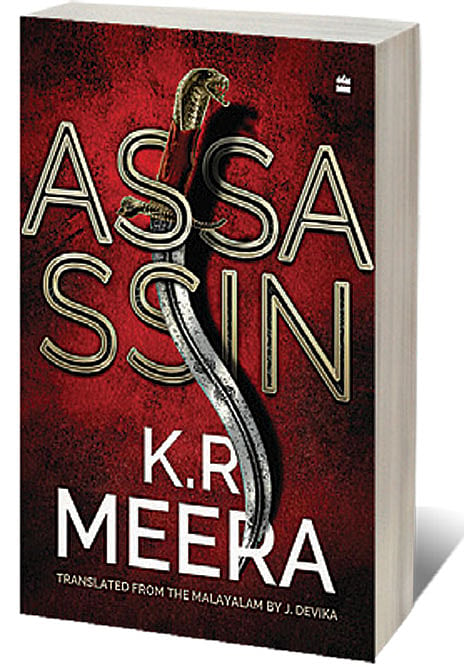

Her latest novel Assassin (Ghathakan, translated from Malayalam by J Devika; Harper Perennial; 654 pages; ₹699) not only furthers her oeuvre but also cements it. Having written more than a dozen books, a Meeraesque genre has now emerged. It is identified by a plot packed with drama and bereavement, and recounted with the lavish sentence. If she is considered a ‘literary heavyweight’ in today’s publishing landscape, it is because she takes the everyday and makes it epic. The arcs of her narratives, the details of her plot are always magnificent and never middling. Her books risk leaving the lily-livered a tad queasy given the ceaseless repetition of blows. There is no let up here, and very little reprieve. Reading them can feel like swimming with the sharks.

The Author’s Note in Assassin concludes with the sentence, “Have you ever faced an attempt on your life? Gauri Lankesh had. I dedicate this book to her.” The novel opens with the line, “Have you ever faced an attempt on your life?” This segue from fact to fiction, this drawing of a straight line from truth to novel captures the essence of Meera’s work. Meera had never met Lankesh but was deeply affected by her death, as the activist-journalist had once published one of her stories and they had spoken to each other in the hope of meeting.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The name of her protagonist Satyapriya also asserts Meera’s diligence to truth telling. During a short break on her all-India book tour, Meera says that she wants the reader to ask herself, “Hey, can there be a woman like this? Can she take all these things?” She says, “Every strand of hair on Satya, every cell of Satya is true. It existed,” adding, “I can’t claim that I have experienced everything, but I have been a witness to many things.”

Assassin opens a week after demonetisation has been announced. Satyapriya is just returning home after completing her work at an HR department of a software company, and having stood in long bank queues. Outside the gate of her rented home, she is shot at three times by an unknown assailant on a bike. When she is interrogated by the cops—who seem more interested in slotting her rather than catching the assailants— they ask why a good-looking woman like her is still unmarried in her 40s. She replies, “Luck in love is directly proportional to submissiveness, not beauty.” The import of her reply plays out in the course of the novel as the reader sees Satyapriya as a character of unusual strength and courage. She is not one to chase after relationships nor will she bow down to others.

When her paralysed father learns of this murder attempt, he who has not uttered a word for many years, says, “Satyamole… It’s not a mistake…his target…You, too, may be killed at any moment.” This cryptic sentence ends up being his last. The novel then unspools as a murder mystery, Satyapriya needs to find her assassin, but more importantly, identify his motive.

In order to catch the killer, the reader is taken into Satyapriya’s past, which is filled with trials and tribulations, from her beloved elder sister dying in an accident, to a house catching fire, to the poisoning of a well, to sexual assault in a car, to an abusive boyfriend, to an alcoholic and violent father, to organ harvesting, to name a handful.

While Assassin is a whodunit of sorts it is also much more than that. It uses Satyapriya’s story to explore the meaning of wealth, the fragility of status, the pervasiveness of patriarchy, the persistence of caste and the resilience of the human spirit when pitted against society. Meera weaves these different threads together to create Satyapriya’s life.

Meera started writing Assassin in 2018, in the interim she has brought out other books. But she is quick to admit that this book took a heavy toll on her. She was younger when she wrote Hangwoman and feels this time the physical and mental struggle were more acute. She has been buffeted by anxiety attacks and sleep deprivation and spells of depression.

She explains, “Every writing has its own after-effects. It’s like being a rubber band. When you are a new and fresh one, you have resilience and the elasticity is intact. So you come to the former self very quickly. As time goes on and as you hang more weight onto it, the rubber band becomes loose and it cannot go back to its former self that easily. So I’m just like a very loose rubber band right now. I used to be very strong and resilient at one time.”

To describe the writing process and the last few years, Meera repeatedly falls into violent natural imagery. Her sentences are peppered with words like “lava”, “molten rock” and “tornado”. Words that hint at how writing is not a passive process of merely putting words on paper but instead a far more visceral

exercise that entails digging into one’s own psyche.

Meera asserts Assassin is “an attempt to document the lives of the women of my generation as personally witnessed by me.” She has seen first-hand how violence can affect relationships—both within the family and beyond it—turning them toxic. To document the lives of women today, Meera found herself in an internal “hell” where she had to summon all her forces to continue writing.

As the novel opens at a time of demonetisation, it is little surprise that the vagaries of wealth are a constant preoccupation. Satyapriya’s life is an endless series of taking loans, trying to repay loans, and then being thwarted by interest. Meera says that when demonetisation hit, she felt its pressures even though she belongs to the middle-class. She was far from home and travelling in Chandigarh for a literature festival. As her card was not working, she suddenly found herself in a situation where she only had a few borrowed hundred-rupee notes. She says, “I found that coming from a middle-class family, my faith or my life was always under the effects of the economic decisions the governments of those times have taken. The political happenings determined the cause of my life. It was revealed that the personal and the political were the same.”

Travelling to the airport she noticed long lines of people queuing outside banks and ATMs. And the general sense of shock and despair all around. The only question in her mind was if this was allegedly a way to end black money or corruption, why couldn’t there have been a more humane, a kinder way to do so? She says, “I always remember the writings of Gandhiji from his last years. He said, ‘I am going to give you a talisman. Whenever you are feeling not sure about your choice or your decision, here is your touchstone. You should imagine how it is going to affect the poorest of the poorest people in our country, so then you can take the right or best decision.’ That stays in my mind. Why are our rulers not doing that when they make a decision? When they implement the policy, why are they not thinking about or actually looking at the face of the poorest of the poor?”

It is this concern for the less fortunate that shines through Assassin, which unpacks the repercussions of having wealth, acquiring wealth and losing wealth. Satyapriya’s mother is from a rich low-caste family and her father from a poor high-caste family. Even though her father benefits from his father-in-law’s wealth, the shadow of caste is never dispelled. Gifts from the family are accepted only after water has been sprinkled on them, she writes. Wealth is no guarantee of respect when caste persists. Meera elaborates, “We think that money has no religion, no caste, no class. But poverty, of course, has a religion. It, of course, has a caste. When I was thinking of this novel, I wanted to emphasise the fact that even if the financial condition is strong, as a woman, and if you are not an upper caste, your experiences are different from savarna women of the same plight.”

The effects of wealth—how it can raise a man, how it can crumble a man—play out in Satyapriya’s father. When his film studio is flourishing, he is a man in a safari suit, cruising in a Contessa, and having his way with women. But then his fortunes change and he becomes a bedridden man who needs his wife’s assistance for even the most basic human functions, he is reduced to a man shrinking within a towel.

The parents of Assassin are particularly interesting characters. The father Sivaprasad is a man of no moral standing and compared to his wife is rather unidimensional. In the course of the novel he moves between the villain of the tale to an extra. As Satyapriya says of him, “He became smaller. I paid no attention, never turned around to take a second look. He got what he deserved, I thought. In the end, he was like a locked room in the house.” Satyapriya’s mother Vasantha, on the other hand, is a most compelling character. She is not a typical mother showering praise and affection on her daughters. But what she lacks in sentiment, she makes up for with strength and stoicism. As her daughters go from living in a house by a lake to living in a shack at the mercy of ruthless relatives, she stands undaunted and determined.

Meera says that to create Vasantha she drew a lot from her mother, who even today has a “solution for everything”. Meera’s mother, she recalls fondly, reads voraciously and widely. She can speak on any subject. And often does so with uncommon Sanskrit words because her father, a freedom fighter, used to make her memorise and recite entire editorials from the Malayalam newspapers of the 1950s and ’60s. She would use these complex words in everyday conversation, often leaving her children stumped. Meera says, “My mother is my foundation. She’s the one who got me books. She’s the one who read me books. I don’t remember my mother tying my hair or bathing me or feeding me or packing my lunch box. But I remember her voice when she read to me.”

Meera grew up in a household rich with stories and words. Her father sent her to Gita classes in the hope that she would grow up to be a pious woman. For many years, Meera could recite 70-plus verses from the holy book. Interestingly, Assassin is peppered with shlokas. She says that she initially wanted to become a sanyasin. When I express my surprise at this, she replies, “I always wanted to do what people thought that women cannot do. It was that simple. I wanted to prove to the world that women also can do all the things which men do. Even today there is an underestimated girl in me who wants to prove to the world: ‘You are all wrong about me.’”