Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay: A Different Feminist

WHEN KAMALADEVI Chattopadhyay heard that Mahatma Gandhi was planning to undertake a 386-kilometre trek, from his ashram in Ahmedabad to the Arabian Sea, she was, at first, elated. His plan, she was told, was to scoop up a handful of salty sand and break the government’s monopoly on the production of salt. When, however, she learnt that Gandhi wasn’t intending to take any women with him to participate in this quiet rebellion against the Raj, Kamaladevi’s elation turned quickly to shock.

Women, she told Gandhi bluntly, could and should contribute to every facet of the freedom struggle. The point of the freedom movement, after all, was that everyone should participate—men and women, equally.

As vignettes go, it is emblematic of the kind of woman Kamaladevi was. In 2024, she may have been termed a feminist. After all, she consistently argued for equal political rights, equal pay for equal work, reforms in the divorce and inheritance laws, birth control and the right of a woman to enjoy her sexual life—as much as a man does. But Kamaladevi would have hated the use of that word. It confined her to a box—and there was nothing she disliked more.

A look at her career will explain why, criss-crossing, as it did, so many fields: nationalist politics, socialist politics, feminist politics, refugee rehabilitation, the theatre, the renewal of handicrafts, and even a failed attempt at building a cooperative-driven city for the refugees of Partition (Faridabad).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Kamaladevi was much more than a freedom fighter and a feminist. She was an author, writing on subjects as vastly different as sex and socialism. Her penchant for carrying a typewriter and banging out her ideas, wherever she was, tended to both exasperate and amuse. There was no district or state of India that she hadn’t visited in her post-independence campaign for traditional arts and crafts. She also travelled widely overseas, from Europe to China and from Sri Lanka to Japan. In the US, where she spent two years, she spoke out stridently against racism, cementing her reputation as an activist for civil and human rights. During her lifetime, Kamaladevi also founded and nurtured several institutions: the Indian Cooperative Union, the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the All-India Handicrafts Board, the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, the Association of Voluntary Agencies for Rural Development, the Crafts Council of India and the India International Centre.

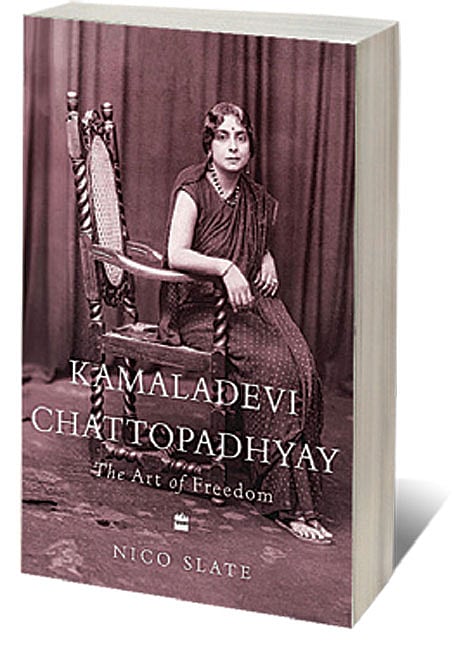

This, then, was not a life destined for a single box. Nico Slate’s new biography portrays the constant tensions Kamaladevi lived with: a life caught between the political and the personal, between feminism and femininity—and revolution and reform.

Born in colonial Mangalore in 1903, she was the daughter of a wealthy mother and a self-made father. Her father supported her emotionally and her mother taught her that gender norms were to be bucked. Tragedy would touch Kamaladevi often. Her father died when she was young, leaving a void where his loving support had been. She was married off at 11—and widowed a year later and this was where Kamaladevi’s fight against tradition began. Child widows, in her day, were expected to live out the rest of their days in austere seclusion. She wanted to do no such thing. It was with her mother’s help that Kamaladevi understood that women had the ability to radically change life as they knew it. It was also with her mother’s help that she was introduced to the wider world of politics. Small wonder then that Kamaladevi wanted more for herself. She enrolled at Queen Mary’s College in Madras—and promptly met the family that would change her life forever.

The Chattopadhyays were an extraordinary family. Aghorenath Chattopadhyay was the first principal of the Nizam’s University in Hyderabad, although he had twice been deported from the state for his unorthodox views. His wife, Varada, was a skilled singer and storyteller. The pair of them produced eight equally extraordinary children, of whom two impacted Kamaladevi in deeply personal and political ways. Sarojini was much like Kamaladevi—unconventional, fiery and brilliant. Harindranath (Harin) would soon be renowned as an actor and a writer. It would be Harin who would not only leave a mark on her life, but who would make her politics very personal indeed.

Going forward, Kamaladevi would meet, befriend and closely work with some of India’s great political leaders. She had a difficult but intimate relationship with her sister-in-law, Sarojini Naidu. She was deeply influenced by Gandhi, but she thought nothing of challenging him. She took on Jawaharlal Nehru in sharp intellectual debates. So intense were their interactions that rumours swirled at the Jaffna Youth Congress about their relationship, especially after Nehru took her rowing on the lake in Kandy. In 1934, she helped found a socialist group within the Indian National Congress and emerged as one of the most influential leaders of the left wing of the freedom struggle, alongside Jayaprakash Narayan and Ram Manohar Lohia. In 1947, at the Asian Relations Conference, she reminded diplomats that international relations was not just about geopolitics, but about the basics like education and healthcare.

With a wealth of material like this, it’s hard not to put together a good story. Slate (professor of History and Department Head at Carnegie Mellon University) has plenty to work with, and he does it with compassion and eloquence. Building on earlier biographies, he adds in newer sources, layering Kamaladevi’s life with both nuance and colour. To say that the best chapters in this book are the ones that deal with her politics would be to minimise the scope of Slate’s work.

Take, for instance, her view of beauty and aesthetics. Kamaladevi saw herself as a woman, first and foremost. She saw no contradiction in embracing traditional women’s fashion, while simultaneously challenging the ways in which tradition limited women. Freedom then, was not just a narrow political full stop, but a pluralistic, inclusive canvas. Small wonder then, that for her, socialism was, as Slate tells us, “defined by a rejection of both rapacious capitalism and totalitarian communism.”

But it is in the private that Slate brings to light the most deeply political aspects of Kamaladevi’s life. Her years as a child widow, for instance, caused her to fight for their rights. It was her failed marriage to Harin that pushed her to argue for reforms in the existing marriage and divorce laws. It would be his constant philandering that led her to fight for women’s sexual freedom and protection. In the story of her marriage and in her missing out on a Cabinet position later, Slate brings out the painful vulnerabilities and paradoxes that lie at the intimate heart of any woman’s life. He writes of her misery at what she saw as her “failure” to keep her marriage going. Divorcing an unfaithful husband seems only natural these days, but in 1933, it was a scandal. “What should I do?” she asked Gandhi desperately, about her dilemma over divorcing Harin. This was the same woman who roundly chastised Nehru for not consulting her before appointing her as the chairperson of the women’s Seva Dal (under the Congress Working Committee). That righteousness was replaced by an inarticulate resentment in 1948, when Nehru appointed Rajkumari Amrit Kaur to a Cabinet position— and gave Kamaladevi nothing but positions that she felt were beneath her.

Today, we think of Kamaladevi as a pioneer for women’s rights. But the rights she advocated were hard won. For her, they came from deeply painful and often humiliating lived experiences—which coloured her politics. Slate has traced sources that tell of Kamaladevi’s conflict over walking away from her marriage; of her pain at being separated from her son thanks to numerous jail sentences; of her struggle to build her own identity in the face of a turbulent personal struggle.

These are the insights that take a political and public story deep into the realms of the vulnerably human. One wishes that there were more of those. Of course, some of that silence is Kamaladevi’s—she never spoke about her life’s most private moments: her years as a child widow, her failed marriage, the birth of her son, her feelings about independence, her feelings about not being given the professional place she knew she deserved. But there are some areas in which Slate himself could have been more vocal. For instance, he touches fleetingly upon what he calls Kamaladevi’s “occasional endorsements of eugenicist thinking,” in some of her early thoughts on birth control. But there is no further discussion of whether there was, in the aftermath of the Second World War in particular, any critique of this view. Then there is Kamaladevi’s possible relationship with Nehru—which is hinted at, but never revealed in its entirety. But these are minor niggles in the telling of a life that is sweeping in scope and monumental in scale.

It is not overstating a fact to say that Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s story is the story of modern India. It is hers and it is historic.