Irwin Allan Sealy: The Kingmaker

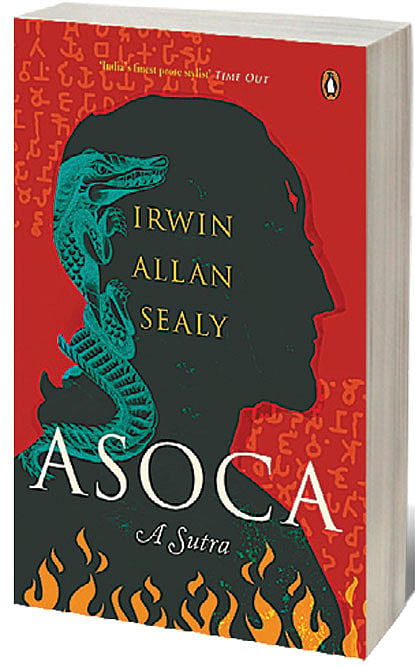

IRWIN ALLAN SEALY first shot to fame in 1988 with The Trotter-Nama, a multi-generational Anglo-Indian family saga. Ten years later, his novel The Everest Hotel, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Sealy is now out with his latest, Asoca: A Sutra (Viking; 392 pages; ₹ 699), a fictional memoir of one India’s most storied royal figures: the emperor Ashoka.

Best-known from history textbooks as a ruler who governed a vast swathe of territory, wrought war and bloodshed, and eventually renounced it all in a sharp turn to nonviolence and Buddhism, Ashoka is a captivating, contradictory character. His imprint remains in the stupas and edicts he left across the subcontinent, which capture his moral philosophy, and were translated in the 19th century.

Sealy’s previous book Zelaldinus: A Masque (2017) also featured a “great” king: Akbar. That verse novel, which played with form and style, explored a once great city too: Fatehpur Sikri.

Asoca: A Sutra, is more conventional in its storytelling approach, going chronologically, and recapping major milestones of Ashoka’s life. As a “sutra”, or “thread”, rather than “a tapestry”, as Sealy writes, the tale is narrated by the king himself, now sequestered in a cave somewhere. It’s a highlights reel interspersed with doses of self-reflection a nd post-facto assessment: from his education and formative years to his father’s death, royal intrigue, the jostle for the crown against his older brother Susima and the Kalinga conquest. A portrait of the Mauryan-ruled subcontinent also emerges.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

There is plenty of action—travel and battle, exile, and betrayal, hijackings and homicides. There is whimsy and humour too, as one might expect in a Sealy novel. “Listener, I never married her,” he cheekily writes at one point, and then, as a new father, “Call me Pissmire… Asoca the Wet”. Kautilya, the wily strategist of history is here rendered as “Uncle K,” a shadowy benign presence, but one with a formidable imprint on the empire nonetheless.

Ashoka has been dealt with in fiction previously, by Wytze Keuning, a Dutchman who wrote a fictive biography that Sealy says he tried to read. He also dipped into scholarship, including “popular histories and academic texts”.

But Sealy is ultimately unshackled by the archives. His Asoca is a novelist’s man, not a historical king, all raw emotions, riven with flaws and inner turmoil. “A novelist takes liberties,” he writes in the preface. “With Ashoka, he must do more, without letting the real man slip.”

Facts are a framework, not an obstacle, and Sealy draws up a richly textured character as he moves through his life. Sealy speaks to Open about Asoca, his writing, the relationship between the present and the past and corny realism. Excerpts:

How long has the idea for this book been with you?

The germ might be a mysterious grainy 19th century photo I saw of the ASI dome over the edict rock at Kalsi about the time I first moved to Dehra Dun. That shelter built by the British kept calling out to me, but I didn’t get around to visiting the place till some seven years ago. I suppose the actual sighting of Asoka’s rock would have been the first prompt. A holy moment. Something of the sort happened with the previous book: a visit to Fatehpur Sikri—one of seven visits as it turned out—set off the train of thoughts and words that led to the writing of an Akbar book, the cycle of Fatehpur Sikri poems that became Zelaldinus.

How did it develop?

A book is usually an enquiry into something: a wild notion seizes you and immediately you feel an ignorance that cries out to be dispelled, a hunger that demands to be satisfied, and that grip, of unknowing, of unease, of uncanny wanting, that insufficiency or lack, is the goad. On the one hand it’s an epistemic craving, but on the other it’s not very different from the need to put food in the belly. So you set out like a hunter-gatherer, except the difference is that you’re focussed on just this Akbar berry or that Asoka root to the exclusion of all other provender.

Why Ashoka? Why now? Did the other fiction on Ashoka affect your approach?

The only piece of fiction I read on Asoka was written a hundred years ago by a Dutchman whose name escapes me: a massive thousand-page tome that I got about fifty pages into before giving up. In fact, I had ordered it online without realising it was a novel. Why Asoka? He’s crucial and exemplary

and his texts are timely. I’ve used one as my epigraph.

[Watch your tongue, Glorify your own faith and you do it harm. Praise

other faiths, don’t slight them. Mix with others, learn from them. This

way you honour your faith and benefit every other.

—from the 12th rock edict, c. 250 BC]

Why now? He’d got under my skin—or I’d got under his. I needed to get the man out of my system.

What do you mean when you say you have “constructed a 21st century king”?

The ideal history book is a recovery of the living tissue of the past, its very DNA. But the cold fact is history is always a supposition, a fabrication; even when you’re trying to relive the recent past, say a journey you’ve just made, you willy-nilly rework that past in the present of the writing. Technically you want to create—for your reader, for yourself—the illusion of living in the third century BC, but there’s a simultaneous realisation of the impossibility of the task. Now, you can either throw up your hands in despair, or you can use the montage of present on past, splice deliberately, knowingly, ironically, commenting on the illusion you’re busy creating; that duplicity is one of the sophisticated pleasures of modern fiction. But you end up with a modern king.

You’ve tackled another “great” King before. What did the process of writing these two characters unravel for you about history, kingship and power? Were there similarities?

You pretty quickly become your subject: you set out to shadow the guy but you end up inhabiting him; you start to think the way he might have thought. Then too you have certain ideas about power, kingship and so on that you’ve picked up along the way and you want to test those concepts on the ground. We’ve all studied history, but we feel this urge to live it; writing a novel takes that leap. You actually do begin to live in that period—swimming back to this shore is disorienting at the end of the working day—and you do learn things about it that didn’t come out of books. That’s one difference between literature and history. Otherwise the strategies were very different with each king.

You write in the preface that “next to nothing is known about the man himself”. Is less information more liberating for the novelist?

Absolutely.

What are the particular pleasures and challenges of writing historical fiction? Has it been done well in India so far, according to you?

I’ve read very little historical fiction, and in fact it’s not a genre that greatly appeals to me, any more than science fiction or fantasy or mythologicals or any of those other evasions of the present. Of course when you do set a book in the remote past you try to be faithful to the time and place, and to the expectations of your reader, but also you are constantly aware of the cracks in the floor or the roof of the fictional edifice, and you occasionally put an eye to a chink in the wall or a wet finger to the draught, and you register that glimpse, or that cross-current: you use the leakage. So I’ve allowed the odd anachronism—say Asoca using the Raj term chukker from polo that’s clearly a 19th century Anglo-Indianism—and that’s one of the pleasures of the text: you’re exploiting the historical disjuncture just for a bit of fun.

Over the years you have engaged with a range of styles and forms. How do you know what approach might best fit a particular piece of work?

You cut your coat to fit the cloth. There’s a whole gamut of traditional forms whose patterns cry out to be applied to your available material—or the material will itself suggest a match. At other times you might just opt for a straight story. For all that I’ve just spoken of the fun of exploiting the slippage between past and present, I did also try in Asoca to be fair to the era (and to the common reader) with a broadly realistic treatment. So this time I’ve opted—I think for the first time—for a straight telling. Call it corny realism, but bear in mind it’s a sutra.

Do you think there is a recognisable category of the “Indian English novel”, and if so, what defines it? By technique, does it need to be “decolonised”, as has been recently argued?

The mature Indian English novel will come another 50 years down the line when it has a desi demotic to draw on; it will be bold and colloquial and effortless and explosive. I’ve often felt hampered by the current thinness of the medium. My own instinct—and my theory, in various essays over the decades—has been to decolonise; in every work I try to discover forms that belong here, outside the West. I have never thought it worthwhile to write a conventional novel in the European sense.

What made you a writer and what keeps you at it?

Anger, ambition, awe made me; a fierce love of letters keeps me going.

You’ve lived all over the place. Where do you consider home? How has your relationship to this country changed?

Home is Dehra Dun, specifically the Small Wild Goose Pagoda. You don’t see your country clearly, or not as a whole, until you step outside it. It’s worth doing.

We don’t seem to see you as much as some other writers at book readings and literature festivals. Have you consciously avoided that?

The one good thing about Covid is that it killed off the literary festival.

Looking back, are you pleased with your earlier work? Is there anything you would change?

No complaints, no grudges, no tectonic shifts. I’d like a little more writing time, but when I get it I slack off more than I should. I don’t regret my fallows or the time spent doing other things. Living fully is more important than writing.

As a reader how have you evolved?

Evolution happens by chance as much as by design: shots in the dark, random drifts, natural selection, a kind of negativity; it wasn’t the black moths that mimicked the soot of the Lancashire mills; it was the white moths that died out.

What’s next?

A gazetteer of the Doon valley, but not the conventional sort. I feel the Imperial Gazetteer of India invented a radically new form; and one good turn deserves another.