In High Spirits

IF KILIAN JORNET had his way, he would be content living the life of a hermit, wandering the high mountains in search of his fix of solitude amid nature.

It’s essentially what he does today, though there’s a spotlight following him wherever he goes. There are days when he considers it to be a part of the job but on most occasions, it’s an annoyance.

Such is his aversion to the limelight that there was a time he considered announcing his own death on social media, after spending many glorious weeks running and climbing around Mt Everest. He dreaded returning to civilisation and his image of a running superstar. Jornet is considered one of the greatest living athletes today: he is a six-time champion of the long-distance running Skyrunner World Series and has won some of the most prestigious ultramarathons. He holds the record for the fastest known ascent and descent of the hardest peaks such as Matterhorn, Mont Blanc and Everest.

Given his superstar status, his aversion to the limelight emerges time and again. But Jornet has figured the right balance, well aware that it’s also how he earns a living today. “I’ve learnt to find the time to ‘work’, either with the press, social media or sponsors, and then found my space and peace when I’m not in focus,” Jornet says.

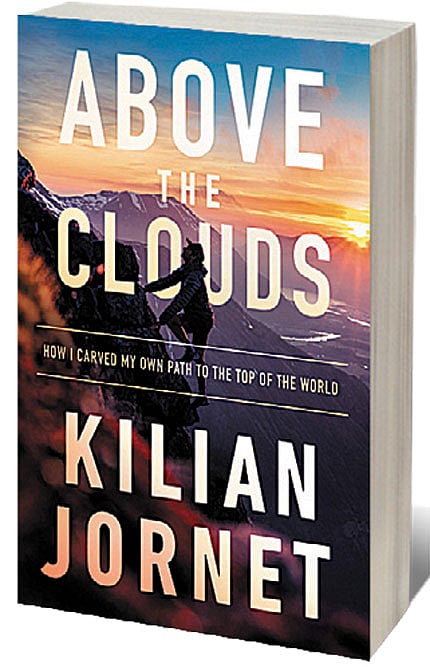

For, as long as he’s in the mountains soaking in the wonders of nature, Jornet is content. In Above the Clouds: How I Carved My Own Path to the Top of the World (translated by Charlotte Whittle; HarperOne; 223 pages; Rs 2,023), the Spaniard relives the affair that blossomed while growing up in La Cerdanya that lies in the Pyrenees and which eventually led him to the top of Everest. And the philosophy that makes him one of the top endurance athletes in the world today.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

His early days were spent hiking, scrambling up slopes and skiing alongside his folks. By 12, he was part of cycling tours that covered a distance of over 150 km.

Once he hit his teens, Jornet discovered his ‘masochistic tendencies’ and that someday, he wanted to be a professional athlete.

“My parents shared their deep connection with nature with me. We were in the mountains 24/7 and I soon realised that in order to learn, I had to fail and try again,” Jornet says.

While most youngsters were getting their first drink or spending time socialising, Jornet was transforming into a performance junkie. He sought exhaustion in his heart and pain in his legs, all in a bid to get better each day.

When he started competing in trail runs across Europe, the early days were anything but easy. For instance, to travel to a distant race, he writes in the book, he lived in the dark for a week to save money on the electricity bill. On another training stint, he abstained from food to understand how long his body could go without it, eventually breaking down at the end of five taxing days. Even today, Jornet willingly transforms into a lab rat when needed, enduring physical and mental hardships to understand his trade better.

“I don’t think of them as sacrifices—more as choices that you make in life. And once you do, you need to accept that another door will be closing because of it. If we consider it to be sacrifices, it means we are not sure about the direction we are taking,” he says.

“It is important to keep learning because we always discover new things. I think my greatest learning has been to accept my ignorance,” he says.

With every win and smashed course record, he amassed a following, drawing attention wherever he went. Over time, the trophies meant little—in fact, he’s given away every single one of them, a few doubling up as a chopping board in the kitchen. He feared ending up as a prisoner of his past. The winning feeling was always welcome, yet competition simply translated to another avenue to put in a few hours of rigorous training alongside the best in the world.

What drew him instead were challenges and adventures in the mountains during the off season. It took him back to where it had all started out for him—running, skiing and climbing, embracing loneliness when it was possible to do so, far from the madding crowd. At the same time, it was all about a continuous, fluid movement on technical terrain to traverse mountains at high speed.

“When I was younger, races were my main motivation. Now it doesn’t interest me much. I rather focus on personal projects to explore different capabilities of my body and the place where I am,” Jornet says.

As part of his project ‘Summits of My Life’ that culminated in Everest, Jornet took on zippy climbs in search of speed records on prominent mountains around the world. During other times, he joined likeminded purists such as alpinist Ueli Steck and mountain guide Simon Elias Barasoain, who believed in a minimalist style of climbing that often threw challenges back at them.

There were times when things didn’t go according to plan; other occasions when he received devastating news of friends perishing in the mountains. But riding on the belief that ‘death would be to not go at all’, Jornet always tries to make the most of his ever-expanding directory of knowledge and resources to improvise when needed.

That in turn continues to add to his fandom—he has a million followers on Instagram—suckers for all-things-Kilian such as his breath-taking ridge runs while linking summits around his current home in Norway.

“It’s dangerous and risky, but it is also something that I’ve done for the past 30 years. You need to think, assess the risk and the rewards, and make a decision,” he says.

“Pain is a situation that is uncomfortable in different degrees. If the motivation to do something is bigger, then the discomfort is very easy to accept,” he adds.

After successful speed climbs up mountains such as Matterhorn, Denali and Aconcagua, Jornet trained his eyes on Everest. By then, he had paid multiple visits to understand conditions on the mountain in different seasons. In the spring of 2017, he set out for the top—solo, without oxygen, communication or camps en route and on a single push. In a span of a week, he announced that he had made it to the summit on two occasions.

It was a revolutionary climb to say the least and Jornet had defined his own style of climbing the highest mountain in the world. His account detailed in the book is an incredible one—stomach trouble at over 8,000 metres, going a second time to make amends for his shoddy first attempt, reaching the summit in relative darkness and even losing his way on the descent. A few have disputed his claim over the years, but he’s made peace with the critics.

“I understand that not everyone will like what I do and the way I do it. But I’ve learnt this and I respect all the opinions. I don’t really care about what other people say,” he says.

In March last year, he embraced fatherhood after the birth of his daughter with partner, Emelie Forsberg, who also thrives in the mountains just like him. Besides projects that make him feel alive, Jornet wants to don the role of a climate advocate in the future and draw attention towards carbon neutrality, conserving biodiversity and

reducing pollution.

“I can bring the conversation to my community, from fans to companies, and promote actions that make a change,” Jornet says.

This book isn’t an elaborate account of his climb up Everest. Like his runs from the deepest valleys to the highest peaks, it traverses key moments that have shaped Jornet—a man at the top of his game, who would be happy to put it all behind him and simply enjoy his next jaunt in the wilderness.