In Conversation with Lawrence Wright

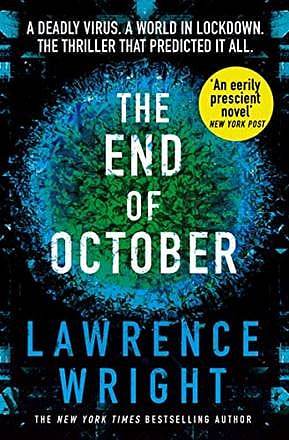

LAWRENCE WRIGHT is an author, screenwriter, playwright and, since 1992, a staff writer for the New Yorker magazine. He is the author of 10 non-fiction books. His book about the rise of Al-Qaeda, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (2006) won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief (2013) was made into an HBO documentary, which won three Emmys. The End of October (Knopf; 400 pages; Rs 699), Wright’s second novel, has been hailed as ‘the thriller that predicted it all’ as it deals with a mysterious virus that threatens to end civilisation. The protagonist, Henry Parsons, a microbiologist and epidemiologist, must try to stop the virus in its tracks, even if it means attempting to quarantine the entire holy city of Mecca after the Hajj. Henry must answer the call of duty, while his wife and two children struggle to survive against hunger and disease in Atlanta in the US. This isn’t necessarily a thriller one would want to read during a pandemic, as it spirals quickly and rapidly into darkness. Speaking from Austin, Texas, Wright discusses disease, religion, journalism and why this novel is not prescient. Excerpts:

The book’s dedication says it is ‘a tribute to the courage and ingenuity of the men and women who have dedicated their lives to the services of public health’. Can you elaborate on it?

Researching the book, I was so impressed with the ingenuity and courage of the people in the public health field. And, bear in mind, this is the step-child of the medical community. All these other specialists are getting rich doing optional surgeries and stuff like that. And here are people who are really dedicated to saving the health of our communities. And they go off into terribly dangerous places, hot zones where novel diseases have broken out and I find that really frightening. This combination of great intelligence and tremendous courage struck me as heroic. That is why I decided to set my novel in that world.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Your main character, Henry Parsons, is an unlikely hero. He is short and walks with a cane. How did you conjure him?

I had a friend who was a professor in Dallas who suffered from rickets. And this same disease afflicted Henry when he was a child. And I admired the nobility with which he bore his disfigurement. And disease strikes us in so many different ways. And I wanted my hero to have been affected by a disease. And rickets is the one I picked, mainly because of the influence of my friend.

Henry is based on a real epidemiologist of the same name. What were some of the challenges of combining fact and fiction?

Henry Parsons is a very obscure figure. He was a 19th century British country doctor, a botanist. But he got appointed Deputy Head of Public Health in London during an influenza outbreak in the 1890s. And at that time, it was thought that influenza was caused by miasma, environmental gases. The word ‘influenza’ is the Italian word for influence. The influences of the environment must make you ill. That was the generally accepted view. Henry Parsons, the real one, was the first to prove that the virus spread by contagion. And it was a huge moment in the history of medicine. When I came across this, I felt this man deserves an acknowledgment. So in a tribute, I named my character after him.

Why do you think he has been forgotten?

For me, it is one of those turning points in the history of medicine. It is totally surprising to me that he is as obscure as he is. Google him, you’ll find practically nothing. It was kind of accidental that I turned him up.

Your novel has been repeatedly called ‘prescient’. But you have said that scientists and epidemiologists have been saying this. It is just that no one was listening. You listened. Also, as a younger reporter you covered infectious diseases. This is a world you know. Why do you think we don’t listen to scientists?

That is a big question. There are many different responses that I could give you. But I think that fundamentally, I have come to believe that people don’t like to give nature credit for the damage that can be done. I think that is one reason why we pay so little attention to climate change. It is one of the reasons that nations blame each other for creating the coronavirus. It is as if nature is not worthy to be our antagonist sometimes. And yet nature does far more damage than terrorists do, for instance. Certainly, Covid-19 has done far more damage to the world economy than a terrorist could accomplish. But there is something in people that demands that we have some kind of agency in all of this. And so giving credit to nature is against our wishes, somehow. I think it is very damaging and dangerous that we don’t acknowledge that nature is a far more formidable adversary, when it turns against us.

In the novel you write, ‘Disease was more powerful than armies. Disease more arbitrary than terrorism.’ Does disease make for the best villain in a thriller, given how it is ‘crueller than human imagination’?

I don’t think of the disease as my villain. You have to acknowledge the power but also the indifference of the disease. The purpose it serves in the novel is as a stress. I decided, look at the civilisations we’ve created. Where are the fracture lines? What is going wrong inside our countries and then add stress to that. And see what happens. And that is essentially how the novel evolved. The virus just serves the function. As a motive force. And society then does what we might fear it will do.

Your book is bleak. Many people die. We’ve scenes where cats are eating owners. Looking around at the unfolding pandemic are you pleasantly surprised at how the community has stepped up?

I am.

I think what I underestimated while writing the novel was the willingness of people to separate themselves, sequester themselves, at great personal emotional, financial, social, spiritual costs, and sequester themselves from society for months at a time. One of the differences with my novel is that food sources and money were hard to get. I think as long as you’ve the assurance that you can access food, and you’ll still have some access to money and electricity… those essential qualities. I think if you broke the food chain, humanity would behave in an entirely different way.

Moving to governments, in your book they don’t come out in the best light. In an interview, you described government responses as a potato-sack race with people just stumbling along the way. But now with the gift of hindsight, what could governments have done better?

It turns out there was a playbook on how to handle the pandemic, one which the Obama administration passed on to the Trump administration. And step by step it tells you what to do in this case. Nobody paid any attention to it at all. I am not just blaming the American government. The World Health Organization has stumbled badly. And there is no sense of direction from an international body.

Different nations have handled it differently, in some cases well, in some terribly. In our government, the federal government decided not to take responsibility and left it to the governors. And some of the governors left it up to the mayors. Everybody is improvising. At a point when there is actually a plan. There are very few entities that are actually following a plan. Those that are following a plan are doing well, those that are not are suffering a catastrophe. And are likely to face an even greater one.

Let’s talk about the lockdown. In India, for example, it is said to be the world’s strictest. In the US, it became an issue of liberties and rights! How do you see the lockdown and the way different countries have responded to it?

Well, one can compare the United States to China. They are totally different societies. One is autocratic… the other is chaotic… ! The Chinese disassembled and hid the disease for weeks. And that was inexcusable. And that is characteristic of that government, with SARS they did the same thing. But when it came to the point that they had to confess, and they were threatened with further catastrophe, they exercised the powers they had. And the Chinese people—I am not going to say willingly—conformed. And it has apparently been a great success in terms of shutting down the virus.

In America, we are so divided. It is so dismaying, honestly, that a disease like this which should be a unifying factor has actually become just another element in the culture wars. And the question whether to wear a mask, for instance, is a way of declaring your political affiliations. And that is a tragic indication of where we are as a country.

Sitting in India, we watch the protests over George Floyd and police reform spill out in the street, and we celebrate that. But one can’t also help but wonder about protests during the time of a pandemic. How do you reconcile the two?

There was a group of public health officials who signed some statement that said that the cause of police brutality is so important, it is okay for people to en masse. The cause is just, there is not any question about it. But if you can go to a protest, why can’t you go to a football game, why can’t you go to a political convention? These are also significant things for people. So this totally puts us in a moral bind.

In The End of October, the Hajj pilgrimage becomes the possible ‘super spreader’. A character even says, ‘We are the victims, but the world will blame us for this.’ As someone who has written extensively on Islamic countries, what were some of your concerns about choosing Mecca as one of the main locations?

I am a journalist mainly. Journalists tend to write about crises and sensitive subjects. Muslims in America are a sensitive subject. After 9/11, when I was working on The Looming Tower, the Saudis would not let me into the country, because I was a journalist. I became an expat worker. I became the mentor of these young journalists in Jeddah, Bin Laden’s hometown. It was great for me. I could assign all these young reporters stories. And one of my first tasks was to oversee the coverage of Hajj. I couldn’t go to Mecca. And I remember my young reporters, they all got sick. Everybody expects to get sick. People come from all over the world, carrying disease, they go to Mecca. And they are closely packed together. And diseases spread. And every year there are epidemics in Mecca. One of my reporters said that he was not going to get sick because he takes these little green lemons. And of course... he was in the hospital. Those little green lemons did not do much for him!

I was struck by how dangerous this is. It is not just Muslims in Mecca. Mass gatherings are inherently dangerous from the perspective of public health. Even when I was in Saudi Arabia, I thought what if there was a horrible disease. What would happen? If everyone gets onto the planes and flies back to their countries… they can create a pandemic almost instantly. That was always in my mind. It was a preoccupation. And that is why I turned to it when I was working on the book.

How do you see religion in the time of a pandemic?

Religion has been a theme in my writing. I have written a lot about religion. I was religious when I was a teenager. I am intrigued by the power of religion. And the fact that people who have strong religious beliefs tend to live by them. Whereas people who have strong political beliefs, it does not affect their behaviour at all, necessarily. I have seen the good of religion and the bad. I wrote about the sons of Jim Jones and Jonestown [The American cult leader who directed a mass murder-suicide of his followers in his jungle commune in Jonestown, Venezuela]. And the power of a single religious entrepreneur like Jim Jones to take people to their death literally. It really struck me.

Historically, diseases haven’t been good for religion. After the Athenian plague, there was a period of paganism. And similarly, after the Black Death, in the 14th century, religion was not overthrown entirely, but was discredited. Religion had no answer for the outbreak. It took time for religion to re-establish itself as a moral force.

You’ve mentioned before how journalists are seldom asked their religious beliefs. They are asked their political beliefs. Could you tell us about your own journey since you mention you once were and are not religious now?

I grew up in the Methodist church, which is not known for its extremism. In the early days of Methodism, it was a despised sect by many people. My dad taught Sunday School. And we went to church. I became part of a Christian youth movement in high school. I was very engaged with that. I went off to college and broke away from that community, and it lost its grip on me. I began to explore other ideas. I started to read existentialism! That was probably the moment when I turned away from religion and opened myself to other ideas. Yet I never lost the sense of respect that I have for religious beliefs and for the people that are committed to a way of life. Even if what they believe is absurd. As almost everything religious is. I wrote a book on the Amish. These are beautiful communities and they are founded on religious principles that I think are crazy. But the effect on their lives is beautiful. It is a contradiction that I observe. And I respect the role of religion, while also guarding against its undue influences.

You’ve said before that when it comes to work, you either choose something that is important or fun. How did you decide on these two lodestars?

At some point, probably just before I got the job at The New Yorker, I realised that a lot of the times I was writing about things I didn’t care about. I was taking assignments. And I was lucky to have them. But it is also my life that I am spending on these stories. So I decided… how should I choose to spend my life and my talents, and well, I thought I want to write things that are important. And I stopped there. But then I realised there are things that may not be important. But I don’t want to lose the joy that comes along with our profession. We are so fortunate to be able to write about pretty much anything and to follow our curiosity. And to let it lead us to places most people aren’t allowed to go. And to talk to people we admire or hate, and to confront the good and evil in others. This is extraordinary. Sometimes it is important and others it could just be fun. And I decided that was the axis that was going to determine my career. And I’ve never found another element that I needed to fit into. It doesn’t need to have three sides. It has guided my life ever since.

Has your definition of what is important changed over time?

I did do a column on being a father. I didn’t take it too seriously. But it meant a lot to me. And now I look back, I’m so glad that I acknowledged those moments in my children’s lives. Nothing could be more important to me than that.

Looking back, what would you say are some of the most important stories you’ve done?

I am always on the lookout for a great story. It is all I really want to do. For me it is the most important and pleasurable assignment that I can have in my life. So when I stumble on a great story, it is exhilarating.

Some of the stories that have been the most important to me have been the most tragic ones. I wrote about Jonestown. I interviewed the three sons of Jim Jones. It was devastating. It was one of the saddest things I ever did. I learned so much from that. I wrote about the Americans who were beheaded in Syria by ISIS. I spoke to the family members and so on. It was sombre. And tragic. But I felt so privileged to have been given the opportunity to tell that story.

Writing about Al-Qaeda and 9/11 was more like a mission than an assignment. It felt like the most important thing that was happening in my generation. I had lived in the Arab world. And I knew something about that. And not many reporters did. I just felt it was on me to get out into the world and find out what actually happened. It was a very lonely period. It took five years. I was away from home a lot. But I knew it was an important story.

How do you keep yourself okay while reporting these difficult stories?

It is not possible always to keep the emotions at bay. I don’t understand how you could be a journalist if you did not have a strong element of empathy. And wanting to understand other people’s lives, that is a fundamental aspect of journalism. Sometimes when I am writing, I am weeping. And I know at those moments, I am touching something that is deeply human. And it is up to me to convey the emotion that is proper for the occasion. And it is a tribute to the suffering that my characters have endured. To treat it lightly or glancingly would be almost criminal, from the perspective of a journalist.

Right now in the US—and one can say even India—the journalist is often seen as the enemy by the government. What do you make of the relationship between journalists and politicians today?

I am sorry that it has come to a point where both sides hate each other so much. The press in the United States is divided but largely antagonistic towards the government. There is a great deal of suspicion inside the government of the press. And it wounds our democracy. The role of the press is to hold people accountable and also to understand what is going on. To get a perspective from the government and from its critics on where we are and what to do next. And who else is going to do that? That is our job. Get the information. And solicit the views on all sides. When governments turn against that process that means they are fearful of hearing contrary views, and it is just a step towards autocracy. When the government is leaning in that direction, that is when the press is seen as the enemy.

What important or fun projects are you working on?

The New Yorker has asked me to write a historical account on how we got to where we are when it comes to Covid-19. That is a big question. How do you tell such a story? I always try to find representative characters who embody a portion of the story and tell their story, so you can see the country through representative figures. I am trying to cast it now. In terms of fun, I am working on a musical on Texas politics. It makes you want to dance and sing. It has been tremendous fun. What you and I do normally is very solitary. But having collaborators can be a great deal of fun.