Homeward Bound

WHEN MANOHAR Shetty was a 14-year-old at St Peter's, a boarding school in Panchgani, Maharashtra, he started writing short stories in the style of O Henry with a "surprising ending, a twist in the tale". He remembers an excellent English Literature teacher who taught them Shakespeare's Macbeth and Julius Caesar. The same teacher shared his short stories with the rest of his class, making Shetty "inordinately proud" as he wasn't "much good at anything else—except chess". As a child, he read the adolescent exploits of Ken Holt—a Bruce Campbell character who travelled the world with his foreign correspondent father and solved mysteries, and JCT Jennings—an impetuous British schoolboy created by Anthony Buckeridge. He also read, a little of Biggles, besides the Westerns of JT Edson and Oliver Strange.

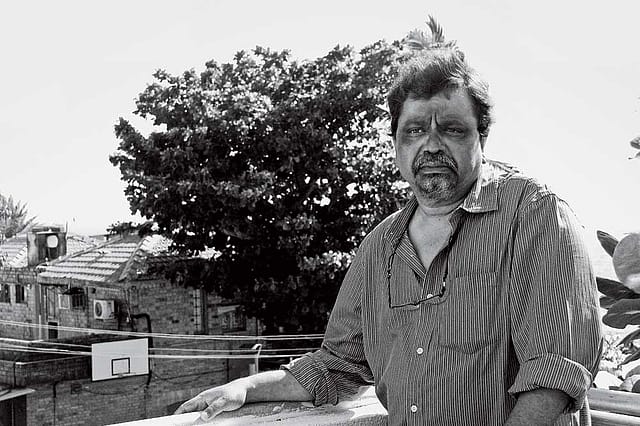

At 64, Shetty has eight books of poetry to his name, not to mention the three anthologies he has edited. "The animal imagery of Ted Hughes, and the craftsmanship of other contemporary poets like Heaney, the early Derek Walcott and Norman MacCaig" have had a subconscious influence on his poetry. He describes the Penguin Modern Poets series, which he chanced upon in a Bombay bookstore when he was around 19, as "an appetiser" which led him to buy several full-length collections by Hughes, Heaney, Robert Lowell, Thom Gunn, Douglas Dunn, Sylvia Plath, DH Lawrence (his poetry) as well as poetry in translation—Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Neruda, Enzensberger and others.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

He lives in Dona Paula, Goa, with his wife Devika and their two daughters, Shaira and Riya. He writes on his dining table in dated diaries. The 200-year-old table is five-feet in diameter and beautifully crafted out of rosewood. "I always write in longhand first," he says. As he writes, at his side is an ancient edition of Roget's Thesaurus (originally published in 1852), which he has used for years.

His new book, boldly titled Full Disclosure New and Collected Poems (1981- 2017) (Speaking Tiger; Pages 283; Rs 399), released recently. Goa has been his home for 30 years, and the photograph that drapes his collected poems is a tribute to that home. "Quite a striking image, I thought," as he explains it, "more so as there are about a dozen or more poems that relate directly to Goa." He appreciates "this rather brooding image with a hint of sunlight of a church in Nerul in Bardez—which goes well with the tone and tenor of the poems". On choosing a title for a collection that spanned 45 years of writing, he says, "I went through several titles, including Engravings in the Air, Legacy and Heirlooms, but settled finally on Full Disclosure which seemed to go with the 'confessional' nature of many of the poems."

Two small presses who pioneered poetry in Bombay, Melanie Silgardo's Newground and Adil Jussawalla's Xal-Praxis, brought out Shetty's first two books of poems: Guarded Space in 1981 and Borrowed Time in 1988. In those days, the first print run on the old letterpress was only around 500 copies, and the books were largely sold by word of mouth in Bombay. Speaking of the age that laid the groundwork for contemporary Indian poetry, Shetty recalls, "Silgardo's press, Newground, also published Eunice de Souza's collection, Fix. And besides Xal-Praxis, Adil Jussawalla also brought out the Clearing House series, with their distinctive size and covers designed by Arun Kolatkar who was also a graphic artist. Adil was the shaping spirit behind that series."

He remembers "informal readings at the NCPA lawns which Adil presided over" as well as "readings at Kamala Das' residence in Churchgate". His own first reading, which he confesses was "nerve- wracking" was at the Stuttgart Hall in Max Mueller Bhavan in the late 1970s.

Shetty notes that poetry's circumstances in India aren't very different from the time he started out. He laments that poets still struggle to find mainstream publishers and acknowledges that he's been "a little lucky" to have been previously published by Oxford University Press and Harper Collins, in a time where "poets still rely on small presses like Poetrywala and Copper Coin". But he does feel that "a sea change in printing technology from the old letter-presses" has made it much easier with eBooks and computer-driven technology. Yet, he still holds on to his old portable typewriter which is "like a museum piece"—an Olympia still in good shape though he no longer uses it.

He shops at the local bookshop in Panaji, Goa—an institution called Broadway which stocks both second- hand and new books. Some second-hand titles he has picked up and has been reading recently are Blackberry Wine by Joanne Harris, The Indian Clerk by David Leavitt, The Outcast by Sadie Jones, The Road Home by Rose Tremain, and novels by Henning Mankell. He has become "a little immune to award-winning books, but may read them when they're non-trending (and cheaper)". He has also been trying to rekindle his interest in science fiction mainly with the work of JG Ballard and Stanislaw Lem.

Though he doesn't dabble in painting, he does try "to paint in words". His interests extend to cinema where he has both written a screenplay for a short film and co-written a feature film. The short film is based on one of his short stories set in a Mumbai local train. The feature film set in Goa and Portugal was co- written with the late director K Bikram Singh from Delhi. Shetty says simply that Singh couldn't raise the money. Neither film has yet seen the light of day.

Between his third and fourth book of poetry, there was a long dry spell of 16 years which was finally broken when he wrote the poem, Stills from Baga Beach, which was published in the 2010 collection Personal Effects. Personally, he would say the dry spell was even longer than 16 years because his third book, Domestic Creatures, published in 1994 "contained several poems from my first two books, and some new poems". He points out that "people often remark that Goa must be an 'inspiring' presence" and clarifies that that's not quite how it works: "You need a certain amount of tension and fraught nerves to set off a poem and Goa can be a beguiling place. Though of course, the genesis of a poem is different for different poets." After Personal Effects "broke the hoodoo", Shetty has been "quite prolific with three more full-length collections emerging in a span of four years, besides the 24 new poems in Full Disclosure".

The domestic is privileged in Shetty's poems. He says, "Perhaps, I'm a domesticated animal!" His poems do not "respond 'poetically' to beautiful sunsets or breath-taking scenery, but to those ants in the kitchen , 'their bodies like puffed rice' or to bats their shadows like 'giant bow ties', or that bound crocodile ('its hide like chainmail') rescued by my daughter from a fisherman's net to be released back into the wilds or the 'jiggling asterisk' of a spider, the 'embroidered pillow' of a pigeon's breast or the way a genuine pearl worries itself into perfection ('anxiety becomes me') or the dragonfly seen as 'a trapeze artiste'." But his work doesn't stop at the drawing of an evocative, interesting image. He stresses the need "to make such poems relevant in a wider context so as not to remain as mere decorative pieces."

Currently, he is working on a collection of short stories. On poetry, he believes, "For the moment I seem to have dried up." He stops just short of dismissing the idea of future collections entirely to say, "with poetry, you can never tell… it's like plucking things out of the air and making them whole. You need to be alert to catch that elusive little wisp floating about."