From the Spectral Island

CHATS WITH THE DEAD, opens with a queue of people arguing. They are the dead, and they are indeed very chatty. One among them is the war photographer Maali Almeida, freshly dead, recently murdered. His gravestone would say: ‘Malinda Albert Kabalana, 1955-1989.’ When the novel opens in 1989 he has neither a gravestone nor a body, but he definitely has a voice. And when we first meet him he is using it to argue with the paper pushers in the office of the afterlife, trying to understand where he is and how he got here.

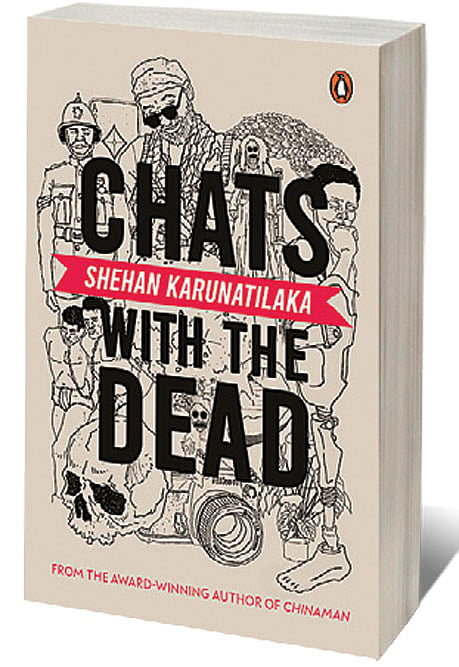

The opening scene of Chats with the Dead (Hamish Hamilton; 400 pages; Rs599) Shehan Karunatalika’s second novel is pure, delightful chaos. The dead are in some sort of post-death holding area, and it’s the kind of hell familiar to most South Asians: a bureaucratic government office. Or as Karunatilaka writes, ‘the afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate.’

Malinda, the war photographer at the centre of the novel will spend the next 400-odd pages, thumbing through scenes from his own life, trying to nail his killer. The victim is also the detective, the ghost story is also crime fiction. “Most ghost stories are about unresolved issues and unresolved relationships,” says Karunatilaka, on the phone from Colombo, where he is based. “But the heart of the plot is a whodunnit. It is a matter of tracing the beats of a whodunnit where you set up different suspects and then you come to a resolution.”

Karunatilaka began writing this book in 2013 or 2014, a few years after Chinaman, his hugely successful, prizewinning debut about an aging journalist on the hunt for a once-famous, missing cricket player. It made the advertising copywriter a star. “For about two years I was doing the book tours and book festivals on it and I was writing a lot of cricket articles and I actually got quite sick of cricket,” he says. “So I decided that if I do another sporting book I’m going to be doomed to doing sporting books forever. I thought the second book should be as far away from Chinaman as possible. That was the intention I started with. And I always thought that Sri Lanka lacked a proper ghost story.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Sri Lanka has been marked by violence, a long simmering ethnic conflict that lasted more than two decades and claimed over 100,000 lives finally ended in 2009. It was fertile ground for exploring the world of the departed.

“The idea that ghosts are people who have died unfairly or died angrily or with unfinished business, then Sri Lanka must be crawling with ghosts,” he says. “We are a country of mass graves and many deaths in the last few decades. That’s why I decided to set it in 1989, which was this perfect storm of violence. You had the LTTE war, the Indian Peace Keeping Force coming and fighting with the Tigers, then we had a Marxist insurrection in the south at the same time and governments that crushed the Marxist rebellion.”

The obvious allegory is that in a war-torn nation, where ethnic divisions persist, the past is an open wound and little separates the living from the dead. In the novel he writes, ‘Being a ghost isn’t that different to being a war photographer. Long periods of boredom interspersed with short bursts of terror.’

The novel is told in a pithy, pungent second-person voice, that is directed at Malinda. “I don’t know how the voice is in other people’s heads, but the voice in my head is obviously in the second person, someone talking to me, like a coach,” says Karunatilaka. “And this idea that the protagonist no longer has a body, but still a voice in their head.” This allows a certain directness in the narration and provides him leeway to cut seamlessly across time and space.

Having his central character work as a war photographer, someone who has not just seen, but borne witness to the horrors of history, offers a rich field of play for the storyline. It allows Karunatilaka to interrogate the past, to invest Malinda with a certain jaded worldview, whilst also setting his protagonist up as a potential target.

To complicate matters further, Malinda is gay, and though he appears to have a girlfriend, he actually has a boyfriend, and plenty of same-sex encounters on the side. Queer rights would have been entirely under the radar in the 80s in Sri Lanka, and that perhaps adds another note of frisson to the novel. To top it off, Malinda is an atheist, with no interest in the afterlife or in being reborn, a fact that only serves to deepen the incongruity of the predicament he finds himself in.

Malinda inhabits this strange world of ghosts and ghouls, spirits and shamans, a world with its code of procedures and interactions. What is his first port of call after leaving the land of the living? Returning to the site where two men are chopping up his body into pieces to try and get rid of the evidence. This is the central driver of the novel: trying to understand how and why he died, and at whose behest. The narrative is full of shady characters and unreliable friends and family members and Karunatilaka is clearly having fun shaking and stirring the detective novel with an extra dollop of the macabre.

But while Chats with the Dead is indeed a ghost story, it is less interested in thrills and chills. The tone instead, is bitterly comic, a tone Karunatilaka says comes more naturally. “It took a lot of research, a lot of drafting and redrafting to get the tone right, because you are dealing with quite a grim subject matter but there are a lot of absurdities,” he says.

Karunatilaka’s tone is almost in the vein of his literary hero, Kurt Vonnegut, combining the funny and the dreadful in a bleak, black way. “His ability to write about the grimness of the human condition but write it in a comic way that is almost joyful, that is something I have always admired,” he says of Vonnegut.

Bodies are cut up glibly, moving through the afterlife feels like drudgery, it’s hard to always tell who is on whose side. “I stumbled in the second draft into this idea that the afterlife is like the Sri Lankan bureaucracy. Like a tax office or an airport where there are all these characters, papers you have to get signed and stamped and no one quite knows where they are meant to be going. This idea of the afterlife as chaos, it could be mined for comedy. I felt with all these restless ghosts roaming around Sri Lanka, maybe that’s why the patterns of violence continue to recur. The ghosts stuck between this world and the next are maybe why we are having such bad luck and why we have such continuing violence and disruption in the country.”

Karunatilaka was himself a teenager in the 80s. His memories are scattered; of schools being shut down, bomb blasts, of concerned adults. “[Violence] was part of the landscape. I wasn’t politically engaged as a teenager, so my memories were really not much. I knew these characters I’d heard these names, I knew what had happened. But it was an experience for me to revisit that 20 or 30 years later. I really just had a child’s perspective on it at the time.

With his first novel, Karunatilaka elided the war, and the island nation’s blood-spattered past, choosing instead to only refer to it in passing, or off-stage. It was a conscious choice. “The war was the go-to subject for many writers. Chinaman was my attempt not to do that,” he says. “Though the war and politics are there, it is essentially a book about cricket. This is my attempt at addressing the crucial subject that I avoided in Chinaman.”

With both books, the research preceded the writing. For Chinaman it was cricket, for Chats with the Dead it was the afterlife. This meant speaking to people, reading books and watching movies, really soaking in the atmosphere he wanted to render, though “I couldn’t interview a ghost” he drolly adds.

Karunatilaka was working in an ad agency when he wrote Chinaman, and “like a million other copywriters”, he had a personal project on the side of his day job. He still works in advertising, and spends months-long stints in Singapore from time to time. But working on this novel was different, because the success of his debut afforded him an audience, and publishing interest. “After 2012 everyone I met would ask when is your next book coming out? When you are writing the first one you don’t know whether anyone will read it, you are writing for yourself. The second one you know there will be an audience, and it will be published and that potentially people will be disappointed. It was on my mind. In the end I tried my best to forget all that and go back to the way I was when I was writing Chinaman, which is just writing the story.”

Karunatilaka is now working on a series of short stories and is also playing around with ideas for a novel. “It’s hard to know when the stories are done, but I would love to get it off my desk as soon as possible. And maybe tackle another novel,” he says. “Hopefully it won’t take me 10 years.”