From Bellary and Bangalore

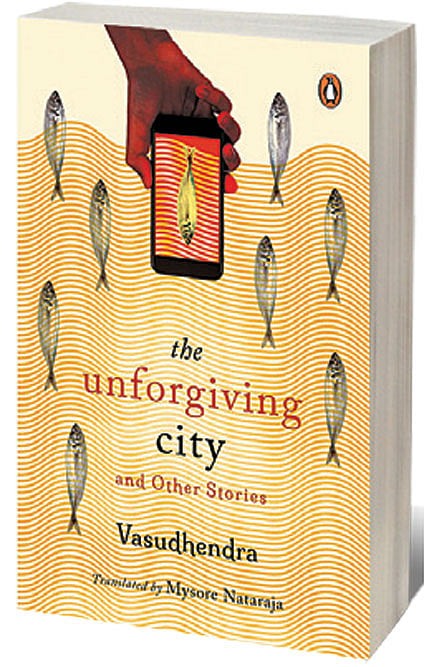

ENGLISH LANGUAGE readers were initiated into acclaimed Kannada author Vasudhendra’s literature when his interlinked collection of stories about a closeted gay man in Bengaluru coming to terms with homosexuality was translated into English and received critical acclaim in 2016. Following Mohanaswamy’s success is his next collection of short stories, The Unforgiving City.

The twelve stories in The Unforgiving City are celebrated in Kannada to the point of being prescribed in universities as essential reading for students of contemporary Kannada literature. Many of them have been translated from Kannada into Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, and Malayalam. “Sometimes I’m not even aware of these regional translations,” says Vasudhendra whose Mohanaswamy (translated by Rashmi Terdal into English) pitched him as Kannada’s first openly gay author.

There is no precise leitmotif to the stories in this collection, yet, Vasudhendra’s fiction reflects village life as a whole including its superstitions and stereotypes, blind devotion and patriarchy. Upon first glance the stories might even pass off as moralistic portrayals, but closer reading reveals how each story brims with intention and clarity, edifying in its own right and laced with unbounded cynicism and social satire.

Most of the stories are set in Bellary and Bengaluru because Vasudhendra finds urban migration a rich canvas to explore the human condition, additionally, his own life has taken that same route. “My life shuttles between the two cities—Bellary and Bangalore and the Hampi Express (a train that runs between the two cities) is like an umbilical cord that connects me to these two cities and sustains me,” he says in an interview with Open.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Vasudhendra is quick to point out how there are no gay stories in The Unforgiving City. “Even though there are some stories in this collection from Mohanaswamy, these are stories published in various Kannada collections,” he adds. He’s keen to not be typecast as a gay fiction writer. The stories in this collection are chosen from Hampi Express (2008), Mohanaswamy (2013) and Vishama Bhinna Rashi (2017).

In the opening story, titled Recession, a couple’s struggle with childlessness meets the travails of modern workplace politics. Vasudhendra examines how personal goals are dictated by free market capitalism and further catalysed by volatile economic conditions in a globalised world. In Recession, written in 2011, a female HR recruiter warns a team lead to not hire a woman in his team because she suspects the prospective hire could end up getting pregnant.

Workplace conflict is a recurring theme; in the story Beyond Rules, the unnamed narrator is morally conflicted whether to hire a recruit with low grades against the company’s rules but does it anyway because he sees potential. What ensues is fleeting vindication of the narrator’s decision but eventually that’s not the moral the story has to offer, rather it transpires into a tale about a voraciously ambitious lad willing to go to any extent to get what he wants. Vasudhendra often turns the plot on its head and takes it in a different direction so in the end, it’s the narrator’s question that lingers; is it the failure of the education system to prioritise grades?

The blunt candour of Vasudhendra’s Kannada prose is seamlessly presented in English translation. “To find a suitable match for Ramabai was not easy; She was dark-complexioned and had protruding upper teeth…. Halikunti was lean and dark and shorter than Ramabai.” reads a description in The Cracked Tumbler, detailing the specific physical attributes of the main characters Ramabai and Halikunti. A few paragraphs later, Ramabai tells her brother who arranges her marriage with Halikunti, in a tone one assumes filled with biting sarcasm: “At least, he doesn’t have buckteeth like me, right? Sometimes there are stories within stories, nested inside each other like a matryoshka doll, just as it is in the case of The Cracked Tumbler.

Vasudhendra says he wanted to examine the cross section between religious devotion and poverty, as is the case with The Cracked Tumbler. “I’m not a god-fearing person but I don’t disrespect religion. I’ve seen extreme devotion among my parents and relatives. There’s so much poverty in rural Karnataka, yet devotion trumps even hunger. I wanted to examine this,” he says. Considering his analysis, reading The Cracked Tumbler, acquires a different note. It’s a clever social satire, disguised as a domestic melodrama.

In the story The Final Offering, the dilemma of owning a mobile phone and the perils of social media overuse is examined. Framed as a mother-daughter love story, the plot eventually crystallises into a damning indictment of Facebook and ephemerality of social media friendships.

The title story, The Unforgiving City, written in 2006 is another brutal takedown of how social media acts as a catalyst to spread contempt and vitriol. “We want to punish people even for their smallest of mistakes. Because forgiveness is not in the interest of others,” he says. The story takes place in a housing society when social media was a different place (in the pre-google era rife with yahoo groups). Yet, yahoo groups or WhatsApp, the medium may be different, the vitriol, less so.

Two Rupees follows an elderly widow who is on a 20-year quest to return two rupees owed to a train station coolie. Nimmi, written as a tribute to Satyajit Ray, whose Brihachchanchu (Terror Bird) it has a passing resemblance to, is about a widower’s multitalented eponymous Pomeranian—she can recognise wrong notes in classical music—whose fame spreads far and wide. The Gift sets up a distressing domestic abuse scene and tries to establish that while it’s possible to sever blood relations, there are certain things that carry forward, like clinical depression, which are sometimes hereditary.

The people in these stories are often god-fearing and Brahminical: “at the tip of my palm resides Lakshmi, in the middle, Saraswathi and at the bottom resides Gowri…” Conflict with regard to meat consumption is a constant theme. Vasudhendra says he’s aware of the focus, but he’s long moved away from it. Considering these stories are from the beginning of his career, one can deduce that the evolution of his literary oeuvre started with him working against a backdrop he was familiar with.

All the while Vasudhendra has constructed a rich tapestry of relatable characters, they are sometimes overshadowed by a chestnut theatrical quality to them—they squeeze their partners’ cheeks and beseech emotionally with clasped hands. The visual elements and tropical melodrama that often form the backdrop to these stories have made them suitable for plays. Bengaluru’s Ranga Shankara regularly stages plays adapted from Vasudhendra’s short stories.

A Palakkad-based theater group called Navarang adapted the play The Red Parrot into Malayalam, Chuvvanna Thatha. It’s easy to see why the story Red Parrot would be perfect for the stage. A story about the impact of mining in rural Karnataka that destroyed livelihoods, polluted the air, and discoloured nature—with fine red mining dust settling on leaves of trees in a pockmarked landscape, and on birds—The Red Parrot is also among the highlights of the collection in its English rendering.

In When the Music Stops, an educated girl from a family with a developmentally disabled brother—as a result of marrying within families— rejects a marriage proposal from her boyfriend after realising the prospective groom is a distant cousin. “I have seen people facing difficulty bringing up a child with severe disabilities. If there is a choice between love and living with a fear of producing an offspring with such disabilities, what kind of choice do you take? That haunted me and I chose to write about it,” he says.

Among the most philosophical of all in the collection, Ambrosia, plays out as a commentary on poverty and the omnipresence of hunger. “We take so much pleasure in eating because this is a society that respects food. On the other hand, hunger brings out a whole gamut of emotions in us, and people are helpless to deal with it when poverty is the reason,” he says.

Vasudhendra stuck to short stories as his favoured form for the better part of his career, yet that has changed in recent times. His Tejo-Tungabhadra (2019), a sprawling historical novel about Portuguese colonialism of India, went into a second reprint early last year. Now the novel is in its seventh edition.

“Mohanaswamy was received well but since my first translation in English was gay literature, I wonder if people have similar expectations,” Vasudhendra says. Even as its writer seems to spurn the grasp of identity politics, his eclectic collection The Unforgiving City doesn’t necessarily shy away from themes of identity. In fact, where Vasudhendra is more successful is when he juxtaposes identity and domestic disharmony against free market capitalism.