Feasting on Fear

I AM A HABITUÉ of a café, near a famous dargah. The owner, who lives above the establishment, tells me that late at night he sometimes hears children crying, sometimes a crowd of footsteps as if a horde are playing on the roof. Djinns, he tells me. This is Hyderabad. A place where the Nizam’s police had an anti-black magic squad. Where the bazaars are teeming with stories of enchanted treasures.

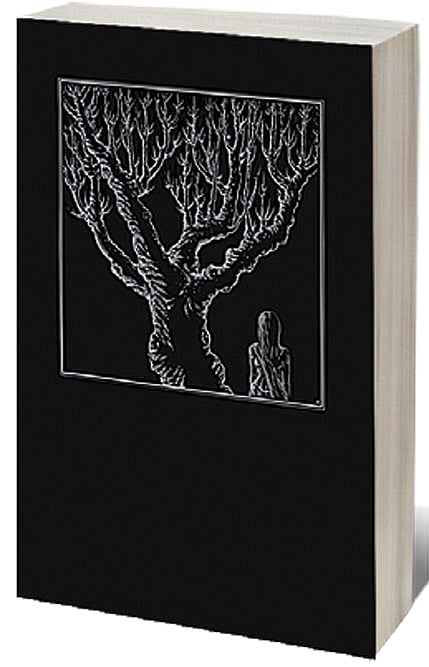

Or as the compilers of Ghosts, Monsters, and Demons of India might say, a ‘necrodiversity’ hotspot. This hefty tome, spread over 455 pages with hundreds of entries and dozens of illustrations, is a welcome effort in compiling the astonishing diversity of otherworldly beings who make the Indian subcontinent their home, from Vedic-era holdouts such as the necromantic Yatudhanas all the way to ghosts who are employed at call centres. There are also those who’ve kept themselves in sync with the changing times, like the Ifrits, one-time firebreathing cave dwellers who now are literally ghosts in the machine.

Some kind of taxonomic principles have to be followed to bring this menagerie in order, phylogenetic trees need to be constructed, and the grounds for inclusion need to be determined. The editors J Furcifer Bhairav and Rakesh Khanna go for ‘a union of sets’— of malevolent supernatural entities, regular ghosts and others who are not otherwise worshipped as deities.

As you browse through the entries, it feels like traversing a colossal hypertext, the denizens of the netherworlds all interlinked, all shapeshifting. A vast and teeming multitude is revealed, abounding with grotesque imagery; decapitated heads reattaching themselves to the body through blind worms, a monster statue with a garland of snails, culminating in the Bagh Dumma, a person who was killed by a tiger (whose) ‘half-eaten corpse regrows so that it is half-human and half-tiger.’

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Entities with high recall value such as chudails are sub-categorised, so are Yetis who come in an astonishing variety; the farthest from the abominable snowman is the Yach, who is ‘slowly balding’ but also ‘likes to dress up as a film star in stylish clothes’.

The entries are also chock-full with useful trivia, for instance Rajasthanis wear bright turbans and colourful clothes because dull outfits are an invitation to the Ret ke Pret or the sand demons that want you to become one of them. In terms of tips and tricks, to navigate these shadowy domains, mustard seeds are like the Swiss Army knife of the underworld, always useful. And iron nails—a surprising number of ectoplasmic entities loathe metal. If all else fails, noisily eat potato chips; certain monsters will assume you are crunching up bones and leave you be.

By far the majority of entities are blamed for unexplained ailments with (what we would call) mental illness or possession coming a close second. Women dying in childbirth get a bad rap throughout.

Spirits aren’t all serious business though; there is the Khuavang, an invisible Mizo earth being which, ‘can cause people to forget what they were about to say. So when there is a sudden lull in conversation, people hold [it] responsible.’

Personally, I found the legends of the dark-skinned Onge, a dying tribe from the Andamans, who live in a world haunted by fair-skinned ghosts, the most haunting. A near-extinct tribe, whose ghosts recorded by anthropologists are the only revenants, in a perverse involution.

The discerning reader will soon discover that this is an encyclopaedia for the post-modern world, where a Borgesian game is played out. You’ll also find an entry on the Onida Devil from the ad campaigns of post-liberalisation India. And a movie monster created by the Ramsay Brothers. The rigour of research ought to be salted with fiction, so follow-ups on giant starfish attacks on the Vijayanagara Empire, or searching for the Red Squid Press in Andhra Pradesh would prove fruitless... perhaps.

This format where Wikipedia-like entries sit alongside urban legends make it an ideal bedside read, something you can dip in and out of. And were you to get invited to a campfire for a storytelling session, it is an ideal reference work if you want to know your bhoot from your pret.