Facing up to the Forbidden

A DAY AFTER BARACK Obama won the presidential nomination for the Democratic party, Nemat Sadat cracked open his laptop and sat down to write a novel. In a few weeks he wrote 45,000 words. It was August 2008, roughly a year before he came out to his family, about six years after he came out to himself. Watching a black man rise to power was catalytic. “Somehow I got inspired by him,” says Afghanistan- born, Washington-based Sadat, 40, while on a visit to India. “He was the first biracial person to win the nomination for a major political party in the US. I thought if he can do that, then I can certainly write a novel.”

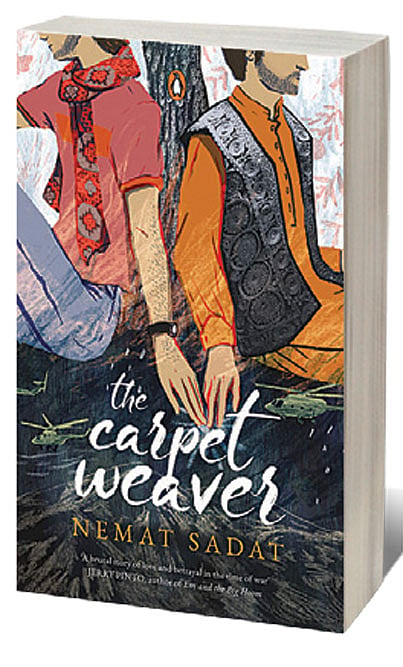

That novel, The Carpet Weaver (Viking; 304 pages; Rs599), was launched in Delhi recently, 11 years and hundreds of rejections since it was begun in 2008. Sadat’s debut novel starts in1977, centres on a teenaged Kanishka Nurzada and his family in a lively, less constricted Kabul. It plots Kanishka’s adolescence, his attraction to his friend Maihan and their beleaguered teenage romance against the backdrop of intensifying socio-political tumult in Afghanistan. Eventually, the family is forced to leave the country, even as Kanishka nurtures hopes for a reunion some distant day in some distant land with his first boyhood love.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

“The novel is not just about one thing but about multiple things. It’s a coming- of-age story or a bildungsroman, and a kunstlerroman as it is the coming of age of an artist, the carpet weaver,” says Sadat. “It’s also about a clash of cultures because the character has multiple identities, and about those clashing identities, which is similar to my life with my clashing identities.”

The lubricating power of the novel is Kanishka’s quest for both familial acceptance and romantic love. Set in a conservative society where homophobia isn’t just socially sanctioned, but practically state policy, since it invites the death penalty, the frisson of the forbidden animates the relationship. ‘The one thing I know is that Allah never forgives sodomy,’ says Zaki jaan, Kanishka’s godfather in the novel’s opening line. ‘Kuni’, as gay men are disparagingly referred to, ‘deserve hell’ another character says in an anonymous note to Kanishka.

The seeds of the novel emerged from Sadat’s own thwarted romances. “I haven’t shared this before publicly or privately, and that is, the history of unrequited love in my own life. Being rejected time and again by everybody I wanted to pursue a relationship with,” says Sadat.

There are easy parallels between Sadat’s life and Kanishka’s: the Afghan roots, taking refuge in the US, Kanishka’s sister Benafsha who was “100 per cent inspired” by his own, identity crises. And for both, there were few templates of romantic love to aspire to. ‘All the romances in the canon of Afghan literature… involved heterosexual couples,’ Kanishka thinks to himself.

For Sadat, as a gay person of colour in the US, there was little by way of reference points in American popular culture. “I felt like a fish out of water in the LGBT community which is predominantly dictated by gay white men from affluent households,” he says. “That was a different world. For me the literature they were putting out didn’t resemble me.” Except oddly enough, one work: Brokeback Mountain, a tragic romance between two white cowboys. “Them living a double life; being married and pursuing romance—it was the kind of double life I was living,” he says. “I wasn’t lucky to have this romance but I was pretending to pursue women in order for people to stop questioning my identity.”

Sadat, a journalist and activist, grew up in California (he left Afghanistan as an infant) and did not know personally the Kabul he captures, whether the art of carpet weaving or the sweaty hammams. The portrait was drawn up from conversations with relatives and family who lived through that period.

The novel’s title refers to Kanishka, the son of a carpet salesman who despite his father’s exhortations to the contrary nurses an artistic passion for carpet weaving. As the novel proceeds, carpets eventually become magical vehicles of the family’s escape; one among other ironic twists that populate the narrative. Threaded through is the sub-plot of his father’s Maoist links, an increasing liability as China distances itself from the local communist networks. The family is forced to flee to Pakistan following an attempted coup and later once the Soviet invasion plunges Kabul into further political turmoil.

For most of the world, the best- known work of Afghan English literature has been Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, which also focused on a young boy in 1970s Afghanistan. Sadat is full of warm praise for Hosseini, whose own literary stardom offered hope for writers like himself, but he was conscious of avoiding the image of Afghanistan as a war-wracked country of barbaric people.

“I have a problem with writers who focus on the clichés and tropes,” says Sadat, who counts James Baldwin, Kiran Desai and Aravind Adiga among the writers he admires. “Afghan literature in the US shows women as subservient and victims of abuse. Men are fundamentalists. There is hatred towards infidels. Of course, that’s true, but if all the books are like that, then that’s a problem. I do show some of that too. But I show the good, bad and ugly. I show the nuanced side of Afghanistan.”

There are the baroque descriptions of foods and festivals, police violence and social stigmas. But also scenes of alcohol induced encounters, sexual advances made by women, and the playful marital dynamic between Kanishka’s parents. “I feel that in order to tell a bigger truth you need to challenge assumptions and propaganda,” he says. “If I do this cliché maybe it will connect with an editor, but do I want to sell out? Or do I want to regret doing that later on?”

Editors were sceptical about the work, he claims. One hoped it could have been more in the vein of Call Me By Your Name, the André Aciman novel featuring a summer romance between two young men in Italy.

It took several years and 450 rejections from literary agents before this novel found its way to the Indian agent Kanishka Gupta on Sadat’s 451st attempt. “I thought I had broken a record,” he says. But he found someone else had 471.

Neither the literary road nor the personal journey was ever simple. Sadat spent a year in Kabul in 2012, first as a development consultant, later as an assistant professor at the American University, where he galvanised a nascent queer rights movement. That propelled him into the cross-hairs of the administration and forced him to leave the country, where homosexuality still remains a capital offence. Shortly after, in August 2013, he came out publicly in a post on Facebook, an act of snapping open the closet door that unleashed a firestorm both in Afghanistan and the diaspora community in America. He received death threats, and his father even asked him to tell the media it had all been a joke. “Coming out for most people is the end of internal turmoil and then they are done,” he says. “For me, I ended an internal war only to start an interpersonal and societal level war.”

But things have since settled, and living publicly as a gay man has been worthwhile, he says. Now he is working on his memoir, and a second novel, whilst continuing to support his causes as an activist. His activism also informed this novel, both in its content and its intent. “Throughout history you see how novels have acted as an agent for social change,” he says. “If I want to be accepted, if I want to help people like me, I thought I can write this incredible novel... Maybe this book can do what Brokeback did in terms of changing attitudes of mainstream heterosexuals.”