People and Peaks

WHEN NEPAL OPENED up its borders to foreigners in 1951, it drew a lot of interest from explorers, travellers and mountaineers. Until then, the ascent of Mt. Everest had only been attempted from the north side in Tibet.

It triggered a race of sorts to get to the top of the highest mountain in the world, which was eventually won by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on May 29, 1953. And there’s been no let up ever since, as the lure of Everest continues to draw romantics even today, which in turn has led to a change in the landscape and dynamics of the Solukhumbu region where the mountain lies.

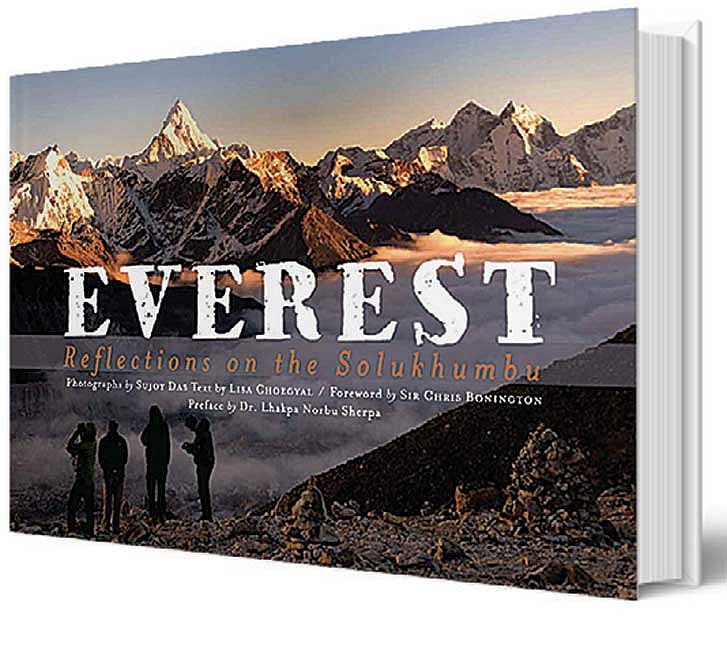

It’s the same allure that has drawn Lisa Choegyal, 68, and Sujoy Das, 58, for years now, and handed them the opportunity to witness how life has transitioned in the valleys at the base of the high mountains. On Hillary’s centennial birth anniversary year, it was what inspired the two to collaborate on their second book, Everest: Reflections on the Solukhumbu (Vajra; Rs2,250; 77pages).

In 1974, Choegyal first visited Nepal, where alongside her brother, she braved a winter trek in the Everest region.

“Narrow trails, precarious bridges and simple teashops—toilets and hot water were a rarity. A very different place from today,” she recalls.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

But her joy was boundless, surrounded as she was by iridescent pheasants and wheeling flocks of doves foraging in the naked fields and long-tailed magpies scolding them for their intrusion. In fact one night, they were stirred by the shouts of villagers, and she spotted the black outline of two Himalayan wolves, racing across a white snowfield, high above the grey stone houses of Pheriche.

Once she moved to Nepal and found employment, she had further opportunities to spend time in the Solukhumbu. What stood out for Choegyal was the hospitality of the local community of Sherpas, who subsisted on farming and trading, until trekking and mountaineering drew their services on the high mountains. Once the airstrip at Lukla was established in 1961, it opened up the floodgates for visitors, which in turn has brought great prosperity to the region over the years.

“In the early ’80s, there would have been maybe 5,000 tourists a year in the Sagarmatha National Park; last year, it would have been somewhere around 50,000. These days, accommodation options range from USD 15 to 200, and mobile phone and connectivity extend all the way to Everest Base Camp. There are also money changers and ATMs, bakeries and cafes en route. Everest is no longer a wilderness experience,” says Das, who first visited the region in 1978 and today guides clients in the region as part of South Col Expeditions.

The infrastructure growth and the influx of outsiders have taken a toll on the fragile ecology to a certain extent, but at the same time, it’s enhanced the life of the Sherpa folks. But their welfare was first tended to by Hillary, who was indebted to them for helping him ascend Everest. As he made repeated visits to Nepal, he formed a strong bond with the community.

Choegyal narrates how Hillary had asked the Sherpa people what he could do for them. Their response was, “Our children have eyes but they are blind and cannot see. We would like you to open their eyes by building a school in our village.”

Hillary attempted to bring about change through The Himalayan Trust, established in the ’60s. Over time, he set up educational and medical facilities—27 schools, two hospitals and 12 medical clinics—which Das says is a phenomenal achievement given the remoteness of the region.

The change that has been effected by The Himalayan Trust over the years has been well documented by Choegyal, who even had the opportunity to rub shoulders with Hillary and his family. She mentions how the first graduates of the ‘schoolhouse in the clouds’ went on to hold prestigious positions at organisations such as the World Wildlife Fund for Nature and in the Nepal government.

“Hillary would have been very proud that his work in the Solukhumbu has been so effective and is now managed by the Sherpas themselves. Sujoy and I wanted to back the efforts of the Himalayan Trust, so we decided to donate all proceeds from the book to them,” Choegyal says.

The book has photographs that Das has made over the last two decades, which document the lives of the Sherpas and their attempts to balance the old with the new. For instance, a stark photo of a pool table in a cafe at Namche highlights the entrepreneurial abilities of the Sherpas and the advent of commercial tourism. But given their reverence for the mountains, Choegyal also explains how the community was instrumental in setting up Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee in 1991, when commercial climbing was just about finding its feet on Everest.

“The case study of tourism in the Khumbu is one of the best examples in Asia of local people taking control in their area and benefiting from it. In an emerging country like Nepal, commercial mountaineering is an important part of the economy. It’s a complex equation, but it would be desirable to see more responsible and safe standards from all expedition operators,” Choegyal says.

With a record 381 permits issued for climbing Everest this season, Das believes that there is an urgent need to restrict the number of climbers on the mountain.

“The proposal to increase the permit fee for climbers from USD 11,000 to 25,000 will help, but I don’t think there will be any regulation on trekkers as the lodge owners and companies will be against it,” Das says.

After having made multiple visits to Khumbu over the years, Das had the opportunity to make friends and gain access to the Dumji festival in June 2018. The only foreign photographer at the event, he highlights the many rituals that he witnessed, besides presenting exquisite photographs from the ceremonies, which he claims have been published for the first time.

His familiarity with the locals also allowed him to document the Sherpas’ daily life and make intimate portraits. He also met some of the legends of climbing such as Kancha Sherpa, who is the only surviving member of the 1953 expedition to Everest.

It was while shooting the Dumji festival that Das shot his favourite image. On a grey, monsoon morning when most peaks were slumbering in the comfort of a thick cloud cover, he was making his way to the monastery in Khumjung under the cover of mist. As he approached a chorten, the sun suddenly emerged to say a quick hello, presenting a mesmerising backlit view of Ama Dablam, which Das considers to be one of the most beautiful mountains in the Khumbu. The fleeting moment lasted all but 20 seconds.

“Though I have more than maybe 200 images of Ama Dablam, this is my favourite,” Das says.

Other than his favourite image, Das has also made some breathtaking images of Pheriche and Cho Oyu, besides other mountains. These come from his wanderings in the Solukhumbu at a time when few hit the trails, handing him the opportunity for the perfect dance with nature. And a few moments stand out for Das even today.

It was during the winter of 2003, when he and a friend, Srijit Dasgupta, were making their way to Kala Pattar and Everest Base Camp. As is mountain weather, the sunny cheer soon made way for a gloom that brought down snow for the next 48 hours.

On the third day, they stepped out in a snowy world that had blanketed the trail beneath it. Even as they pondered their next course of action, a herd of yaks appeared out of thin air and paved the way for them.

“From a featureless, white world we now had a path to follow, a miracle caused by these great beasts of burden, the backbone of life in the high Himalaya,” Das says.