Eternal Seekers

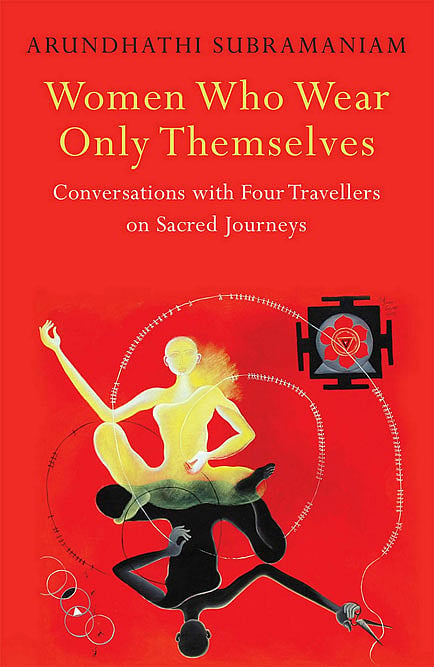

The recurring motif in Arundhathi Subramaniam’s latest book, Women Who Wear Only Themselves, is the idea of seeking. Stemming from her own thirst for conversations with seekers of “various persuasions” and in attempting to re-articulate the stories of four spiritual seekers—all women from south India—the book becomes a sanctum sanctorum for the notion of seeking. Reinforcing the truth that the pursuit of seeking is one that is constant, life-long and transformative, every step along the way, the book has the potential of being more than a one-time read; for it’s a heady reminder that seeking, even for seekers, is a work in progress.

Subramaniam is a poet and writer with an inherently spiritual bent of mind. This book, 13th from her writing stable, published by Speaking Tiger, is a short, thoughtful and nuanced mini documentary—of sorts—of the lives of four female spiritual travellers: “Sri Annapurni Amma, a saint from Tamilnadu, who chose to live naked and sometimes delivers prophecies, Balarishi Vishwashisarini, a gifted teacher of Nada Yoga who admits to sometimes feeling she’s missed out on a read childhood, Lata Mani, a respected academician in the United States who was plunged into the path of Tantra after a major accident that left her with a brain injury, and finally Maa Karpoori, a feisty young woman who is a monk but one who retains her independence and contagious joy of living”.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Even though each of the women who features in the book has a quality and personality of their own, we recognise the “convergences” and the “connections” they share with each other. For starters, they have a quality of quiet about their lives; as women who have made the transition into the spiritual side of life, they have also adorned for themselves a garb that is singularly, fiercely, strikingly, their own. In amplifying some aspects of their lives and throwing open a window that allows us a glimpse into their then and now, Subramaniam becomes also, in a sense, a chronicler, a much-needed public relations agent for lesser-known voices and spiritually anchored contemporary women—whose stories must be told, must be heard.

While two of the women featured in the book are women Subramaniam chanced upon by a stroke of the universe—Sri Annapurni Amma and Balarishi Vishwashisarini—we can sense the closeness and connection the author shares with Lata Mani and Maa Karpoori; their journeys are diametrically different from each other and yet in attempting to find joy in the beauty and simplicity of life, they sparkle despite the stark minimalism they surround their lives with.

Shining through it all—words that are used with thought and conviction; that manage to reveal as much of the outer and inner worlds of these women with empathy and nuance—is the power and potential of female friendships that cut through struggles of caste, faith, religion, hierarchy and recognise the questioning voice of a woman who is as keen to write a book as she is to share it with a larger universe.

Every chapter ends and begins with a poem from Subramaniam’s writings that adds yet another layer of meaning and metaphor to these stories that are full of quiet courage, dressed in an attire called abandon that needs no validation. The poem ‘Textile’, from her book When God Is a Traveller, perhaps best sums up the intent of both the writer and those written about: “… And so you return reluctantly to digging through the seam and stretch/ and protest of tattered muscle/ deeper into the world’s oldest fabric/ into the darkening widening meritocracy of the heart.”