Entwined Lives

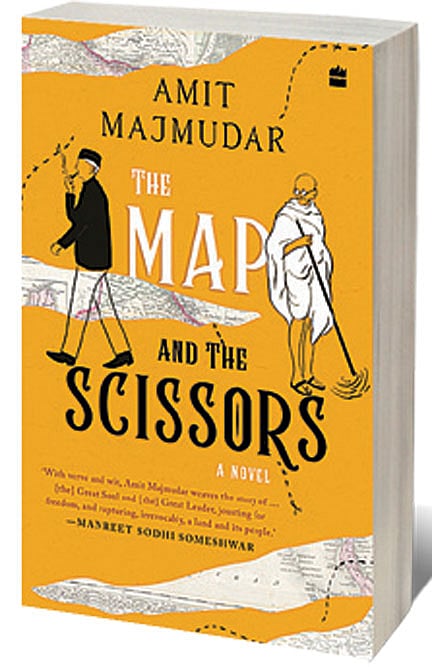

IN ORDER TO GRASP what Amit Majmudar attempts with his latest work, one must consider Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. He studied seminal Greek and Roman historical persons in pairs, such as Alexander III of Macedon and Julius Caesar, one Greek and one Roman, ruminating on their failings and virtues when seen in tandem with each other. In his novel, The Map and The Scissors (HarperCollins; 344 pages; ₹499), Majmudar does much the same with the starkly different but entwined lives of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Ali Jinnah—one of whom sought to keep the colonial map of India intact and one of whom wielded the scissors, one of whom was staunchly Indian and one of whom ended his life as the Pakistani head of state. Throughout the novel, Majmudar pulls observations from Plutarch’s text that feel disconcertingly inevitable, even universal, in the fate of powerful men. It is a novel that grows in impact with each re-reading—the reader’s image of Gandhi turning more complicated the longer he is made to share close literary quarters with Jinnah, and the evolution of Jinnah becoming clearer when seen in reaction to the fakir.

Born in 1979, Majmudar an Ohio-based diagnostic radiologist, was named the first Poet Laureate of Ohio in 2015. In India he is best known for his 2018 translation Godsong: A Verse Translation of the Bhagavad-Gita, with Commentary. He grew up, as many did, with the Gandhi of the Attenborough movie, played by Ben Kingsley in 1982. “That is by no means a bad or incorrect portrayal, but when I began to read books about Gandhi when I grew older, the portrait deepened and gained richness of contradictions,” explains Majmudar. But it wasn’t till he researched and wrote his novel, Partition (2011), that he developed a deeper understanding of Jinnah’s role in the division. He ascribes Jinnah’s relative obscurity in Anglo-Indian discourse to issues of guilt and shame surrounding Partition. “Wherever Partition is considered a negative outcome, or a thing that should have never happened, the discourse avoids foregrounding Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League because it seems Islamophobic, blaming South Asia’s Muslims for Partition,” he suggests, “Blame is shifted instead to the British (who botched the actual execution of Partition, but for quite some time resisted it and advised Jinnah against it) because the British are an acceptable object of vilification.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

He contrasts this with the situation in Pakistan where Partition may be considered “a positive, necessary, even glorious victory” and where “it’s not a question of who takes the blame for Partitioning the Raj—it’s a question of who gets the credit. Jinnah, or at least a (sanitised and pious) version of Jinnah, is foregrounded. He is on the Pakistani rupee note. The Pakistanis know quite well who he is and what he accomplished.” Returning to the subject of Partition with The Map and The Scissors was a way of “incorporating [his] new knowledge of Jinnah with [his] pre-existing knowledge of Gandhi”— of coming to a fuller understanding of the Independence struggle and its outcome. Where Partition was a story about regular people caught up in the upheaval, The Map and The Scissors studies the political intricacies that led to it.

On the one hand, Majmudar sought out every kind of nonfiction material: accounts by historians, oral histories, archival documents such as speeches and transcripts of the Partition negotiations, Gandhi’s own autobiographical writings (Jinnah left behind no memoirs), and photographs and newsreels. On the other hand, he was careful not to immerse himself in the research. His first foray into fictionalising the subject was with a tragicomic short story in 2004 called, ‘The Troubles of Taqlif Husain,’ which was concerned with the problems of an old man whose house was precisely bisected by the Radcliffe Line. While The Map and The Scissors is a far cry from the dark, sometimes oppressive comedy of that tale, it has similar moments of satire and comic relief such as are shown in the plight of British officers tasked with managing undivided India’s final years.

In 2004, the author had little inkling that he would go on to publish his first novel on the subject, and publish yet another novel about it 11 years after that. His knowledge and understanding of Partition accumulated over time. As he puts it, “things one is fascinated by get remembered very easily.” As he read, he wasn’t looking for particular details or building towards specific sub-plots, he was simply always “on the lookout.” He explains that his approach was “not to get too worked up about covering every last detail. There is too much out there for any one person to read, and I was not writing a nonfiction book but a novel.” So, he reconciled himself to the idea that he would miss interesting details in his “random dippings” into the archives. But that allowed him a necessary freedom to scan freely and creatively incorporate what he encountered.

He chose to fictionalise this comparative study of Gandhi and Jinnah because it allowed for “surrealist touches, invented dialogue, symbolic episodes and imagery included for their own sake, digressions and speculations regarding private lives and states of mind, elision and selective emphasis for narrative momentum, a preference for creaturely or evocative detail over the nitty-gritty of political negotiations.” In this manner, he was able to show their remarkable differences to their fullest effect.

When I ask him how he decided the finer details of his narrative, such as Mountbatten’s reaction to Jinnah’s veiled threat about his legacy or Nehru throwing himself into a chair after witnessing the violence in Delhi, he tells me plainly that the art of the historical fictioneer remains mysterious to him. “These decisions are often instinctive, and while I know that is not the most helpful or illuminating explanation of the process, it’s the truth,” he posits, “In the planning or information-gathering stage, I read the source documents, stare at photographs...and suddenly some fact or detail jumps out at me, and the writerly part of my brain points and shouts, There! Incorporate that, flesh it out! I know the useful facts when I see them. I rely on whatever radar picks that up.”

Majmudar says he has read very little if any fiction about Partition in order to avoid being stylistically influenced by these works. He says, “I wanted to write fiction about Partition as if no one had ever done it before, so I created an artificial environment for myself where I experienced 1947 almost exclusively from nonfiction books, then transfigured it into my two Partition novels.”

Gandhi’s decades-long quest to conquer lust forms an important sub-plot in the novel. It is a part of his life that has fascinated and horrified people in equal measure. Majmudar argues, “Gandhi was not just a political figure but also a religious one. Until this is understood, until his ‘experiments with truth’ are placed in a religious context, they simply seem strange. His struggles with lust, his fruitarian diet and fasts, his vow of poverty make perfect sense in the context of Hindu asceticism.” Further, he says, “there is a long tradition in India of the ascetic who restrains desire—millennia-old texts describe this, and ascetic self-discipline prescribes ascendancy over one’s own impulses. This age-old religious pursuit of self-restraint and self-mastery took that form in him.” He even sees parallels between the physical self-discipline (“extreme physical challenges, strict dietary restrictions and so on”) of the ancient Hindu India’s ascetic subculture and contemporary America’s fitness-crazed subculture.

In more ways than one, Majmudar’s newest work is a meditation on meaning-making, the power of stories and the impact of storytellers. Both Gandhi and Jinnah are readers, and the text draws heavily from quotes and literary counterparts to offer insight into these characters, particularly in the case of Jinnah, who is compared to Othello, Lear, Azazil and Lucifer at different junctures in his journey. William Blake’s The Tyger becomes a way to concretise the dream for Pakistan, both the poem and the idea rousing people to believe in things they’ve never seen.

The novel opens with an epigraph from Parallel Lives, which comments on the liberties mapmakers and historians took with depicting lands (and their corresponding inhabitants) which they had either never seen or did not fully understand. The Radcliffe Line inspires the novel’s organising metaphor, named for the famously untrained and under-informed architect behind the line that changed millions of lives. But the novel sees Radcliffe as a bit player at best in a political landscape with far more influential players. He drew a critical line with impatience and indifference, but the schisms had formed long before he ever set foot in India. It is ultimately Jinnah who takes liberties with the map, not some shadowy cartographer from the West, but a man to whom borders are a way to consolidate power, who Majmudar has mouth Lear’s sinister words, “Give me the map there.”

The author observes, “In the worst case, artists can become propagandists and falsify history, whether by pretending only one group perpetrated violence against the other, or by making skewed and self-exonerating claims like, ‘It was all the fault of the British.’ I think any reader of The Map and the Scissors can confirm that, whatever its faults, it didn’t do that. I honoured the complexity of the situation and the perspectives.” Though the novel can read like an indictment of Jinnah, it makes his catastrophic metamorphosis comprehensible, if never justifiable. Similarly, Majmudar’s portrait of Gandhi is that of a well-intentioned leader whose naivete and other shortcomings ultimately aid Jinnah’s cause. Whereas BR Ambedkar recognised the village as a site of ossified darkness, Gandhi saw Indian villages as the antithesis of Westernisation. “He cannot bear,” writes Majmudar in the novel, “to see it bleached white.” In one instance, Gandhi refers to himself in an off-hand way, as a Christ-like figure.

Both men are shown as a set of contradictions, “skeletal” yet larger-than-life, frail yet influential, clever yet victims of their biases. The power of the novel lies in the fact that it uses the premise of Partition to understand India’s history better. The novel makes, particularly in the second half, for compelling reading as it dramatises the final act for these leaders. It may not be history, but it feels true in a way that doesn’t feel unfair to either of these men, while being far from overly forgiving.