Earth Mother

OUR FARMLAND WAS rain-fed, and cattle were important in the scheme of things. They were helpful in activities like irrigation, ploughing and husking. The cow dung served as manure. We earned more selling milk than we did from farming. The droppings of goats fertilised the land and their meat sold for a good price.

For us, agriculture revolved around the cattle. We sowed maize but harvested the corn cobs before the plants matured. Otherwise, the stems would dry up and become unsuitable for fodder and could injure the mouths of our cows. Throughout the year, cattle fodder was the most important concern for us. Similarly, we could make do if there were no rains or no yields from our groundnut plantations. What we worried about was that the creeper—round-the-year fodder for the goats—was healthy. The important tasks of harvesting the crop and drying and stacking hay were also difficult.

There were always some cows and goats in our household and the whole day’s work was centred around them. The sheep grazed all day, and one of us was always watching over them. It was not easy; we had to be on our guard day and night—monitoring the pregnant ones, safeguarding the kids and managing the rams when they caused trouble. If the sheep were hungry at night, they would bleat pitiably, non-stop, and disturb our sleep. We had to shepherd them to the grazing lands and have them drink plenty of water. If they didn’t manage to graze enough, we fed them dried groundnut plants and leaves of the castor plant until their stomachs were full.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

It was impossible for people who had goats and cows to travel out of town for a few days. If we absolutely had to go, we would have to make arrangements for someone to look after them. We would then worry whether that person would look after them as well as we do, and that would stress us out.

Amma was closer to our goats and cattle than to most people. She named each goat and every cow, and called them by their names. She could tell apart the voices of all the goats. If one of them bleated, Amma would talk to it and it responded to her voice. At least one goat kid could be seen trailing her all the time. The goats birthed several young ones in a litter and would not have enough milk for all of them. So we would bottle-feed a couple of the kids and they would grow very fond of us. When the cow’s yield was plentiful, Amma would go to the market and buy a kid, which would only be bottle-fed. These kids always followed us around and Amma loved it. She could not live without goats.

Towards the end of her life, Amma was sad that she hadn’t raised goats for a few years. For an old person living alone, a single goat is all the company they need. They can share their life stories and memories with it. No human has either the time or patience to listen to old people. But all a goat needs is to be stroked—it will respond to the love and listen tirelessly.

If Amma began a conversation with: ‘Let me tell you the story of my father. Listen!’ or ‘Let me tell you the story of my husband,’ or ‘Will you listen to my children’s story?’ the goats nodded their heads and listened. They always had a sad look plastered on their face. When Amma narrated her story, they seemed to look sad for her sake. They also occasionally bleated in empathy. ‘If I just had a kid goat, my needs would be taken care of!’ she often said—the income from a single goat was sufficient to put food on her plate.

I wrote many poems in my younger days. They were filled with empty dreams and fantasies because those were the kind of poems that I got to read. Taking inspiration from them and imitating them, I wrote prolifically. I participated in poetry competitions in school and college. Mistaking ornate language for poetry, I used to regard even snatches of comedy and propaganda speech as beautiful verse.

An incident from when I was a first-year undergraduate student changed my perspective. It involved Amma and the goats.

It was summer. Our house near the fields consisted of three sheds with thatched roofs—two had walls and the third only had a thatched wall. My grandparents lived in one. Since they were old and there was no electricity, they would have their dinner early and lay down on their cots. Another hut was used for cooking and to store utensils. During winter, Amma and I slept there. My father and brother used to get back home only at two in the morning after minding our shop in the cinema theatre. The shed without walls was used to store fodder for the goats and cattle and to tie up the calves. We sometimes also slept there too. On that day, Amma and I were sleeping in the cowshed.

I was fast asleep when Amma shook me awake with,

‘Boy, boy!’

‘What, Amma?’ I asked her wearily, turning over in the cot, trying to hold on to my sleep.

‘Get up and come out, da!’

I understood that it was something important and immediately jumped up. Outside, the breeze was cooler than it should have been in summer. The wind raised dust that swirled about noisily. I still wanted to get back to bed.

‘Why did you wake me up, Amma?’ I asked angrily.

‘See how the wind is rushing! Did you see the sky above? The clouds are gathering. There will be both wind and rain. If you sleep with the thatches open, the wind will carry everything away. Then, we’d have to beat our stomachs and chest and cry over losing this and that.’

I realised the gravity of the situation. Summer showers never came alone and were always accompanied by fierce winds and heavy rains. We usually secured the sheds with ropes to protect them from the winds—we pulled these and tied them even tighter. We collected all our things and brought them in. We tied the buffalo calf inside the thatched shed.

The wind was blowing dust into our faces and we could not even lift our heads up to see. I had a torchlight in my hand. Stacks of groundnut and maize hay were stored in the field a little distance away. They were tied to a rock with ropes attached to four big stones we had placed around them. We checked if they were all right. Unable to bear the force of the wind, a drumstick tree nearby fell. Amma construed it as an omen. The leaves of the palm tree swayed in the wind like a demon.

‘God knows what the wind and rain are going to take away today!’ Amma said.

The sheep were bleating fearfully in unison; we could hear them. We ran towards our corral in the field. The tarpaulin tied with ropes was threatening to shake loose. We checked the knots and then, pushing aside the tarpaulin, we went in. The sheep were huddled together in the middle of the corral, with their heads stuck to each other’s stomachs.

Sheep are known to have herd mentality, they always follow the one next to them. If the first sheep in a herd falls into a pit, the others will follow behind, goes a saying. We had bonded closely with the sheep and understood them well. They have the ability to sense danger and are a united lot.

The sight of them huddled together so tight, as if they were braided together, is something I will never forget. When they heard Amma, they started bleating pitiably. The shed swayed in the wind.

Amma separated three kids hiding amidst the sheep and handed them to me. I slung one across my shoulder, held the other two in my arms, lifted the tarpaulin and ran homewards. The kids were wailing and they weighed me down.

I reached home, covered them with a big basket and ran back to the corral. The rain now joined the wind. The draught swirled the rain into a whip and lashed my back. I kept my face down to avoid the gale and continued to run.

Amma stood inside, holding down the shed as the wind tried to lift it off the ground. A tug-of-war ensued between Amma and the wind. The sheep remained huddled together. I held the other side of the hut and pulled it down. Could even our combined strength match that of the gale? It lifted both of us along with the hut a clear one foot off the ground and then dropped us. The rope that held the tarpaulin broke. The corral rattled in the wind and looked as if it would rip apart any moment now.

We knew that nothing could be done.

‘Untie the ropes of the tarpaulin. Let the sheep run whichever way they want. We can find them after the rains stop. We can’t do anything else,’ Amma said.

I untied the ropes and stepped outside the tarpaulin. Only then did Amma step out of the shed. As soon as she did, the fierce wind uprooted the hut. The timing was perfect. We were stunned to see the shed fly like a bird with giant wings and then fall to the ground against the backdrop of lightning in the sky. Once the shed was gone, the sheep ran amok in the dark.

Amma took my arm in hers. We tore through the wind and rain and somehow managed to reach home. It poured incessantly for an hour after that. We stepped out once it was over, herded the sheep and patched up the tarpaulin.

That night’s experience left a deep imprint in my mind. I wrote it out as a long poem, pouring all my emotions into it. I had the satisfaction of capturing a great experience and took pleasure in reading it many times over.

I realised that all my previous poems were just empty words, and considered this my true first poem. Since then, lived experiences and emotions have occupied a primary place in shaping my poetry.

It was Amma who helped me realise this truth, along with the sheep of course.

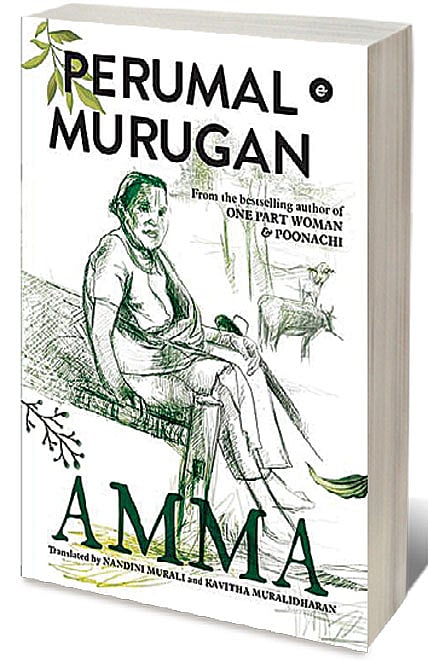

(Amma is translated by Nandini Murali and Kavitha Muralidharan; Eka; 216 pages; Rs 399)