Director’s Cut

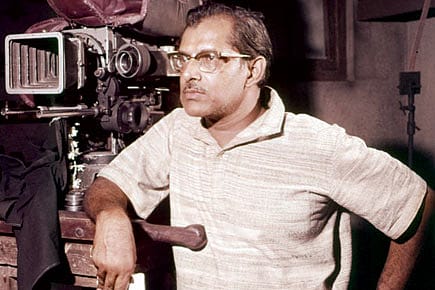

What's there not to love about the film Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (JBDY)? Nothing. Which was also true for Jai Arjun Singh's tightly edited, thin volume on the Kundan Shah classic: Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro: Seriously Funny Since 1983. Likewise, so far as the subject is concerned, Singh has chosen well to explore 'the world of Hrishikesh Mukherjee' (1922–2006, fondly called Hrishida). The book's subtitle, suitably enough, is 'The filmmaker everyone loves'.

But unlike the JBDY monograph, this is a tougher book to write, and for the same reasons, more difficult to read. For one, we're looking at a filmography comprising 41 movies, being critiqued almost simultaneously, rather than chaptered film-wise—unlike, say Shyam Benegal's uncluttered, eponymous 'career-ography' by Sangeeta Datta. Desi movie buffs, particularly of the video generation, have their own favourite Mukherjee movies they remember almost by heart. In my case, it's Gol Maal, Chupke Chupke, Anand, Bemisal, Namak Haraam and Abhimaan. Your eyes naturally light up during portions in the book when your favourite films are being discussed. You want to speed-read passages referencing movies that you either haven't watched or never cared much for.

This is the trouble with a comprehensive analysis of anyone's works. Especially when anecdotes and back-stories are missing, the perspective is totally of a critic/author who has held no interaction with the protagonist of the concerned book. As in the case of Jerry Pinto's mildly tiring Helen: Life And Times Of An H-Bomb. Which is in sharp contrast to a film book where the voice is entirely the protagonist's—like Nasreen Munni Kabeer's excellent Talking Films (with Javed Akhtar). This isn't to say that one form is necessarily more satisfying (for the reader) than the other. That really depends on the content, as it were. Singh's critique of Mukherjee's movies is absolutely first-rate, no doubt. The prose flows well.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The author aptly speaks of polar opposite movies Satyakam (1969) and Biwi Aur Makaan (1965) in the same sentence. Every Hrishida movie, he argues, falls somewhere between the two extremes, where Satyakam represents 'elephant art' (a grim film, commenting on society at large), and Biwi Aur Makaan, which epitomises 'termite art' (made for frothy entertainment alone). He also places the director's works or world before us as a makaan, which is a fine metaphor, given that Mukherjee's 'Middle Cinema' was so much about relationships and soft dramas taking place in living rooms of middle- class homes.

Inside this Hrishida's makaan (pardon the pun), we explore motifs that recur often—characters leading double lives, the concept of natakbaazi (or role-play) in the narrative, the importance (or unimportance) of the moustache, the changing role of the doctor, the two opposite types of old men, and the actor David appearing in film after film, purportedly as the voice of the director himself.

In current Bollywood, obsessed with stardom and Rs 100/200/300 crore box-office clubs, how relevant are Hrishida's films? Hugely, if you take Raju Hirani, presently India's most commercially successful filmmaker. Also an editor-turned-director, he is widely considered Mukherjee's creative progeny. Hirani's hits (Lage Raho Munnabhai, 3 Idiots, PK), like a lot of Mukherjee's movies, administer 'sugar-coated pills' to mainstream audiences. They are social commentaries delivered through light-hearted banter, good-hearted characters, and effective use of music and super-stars.

Further, some of Mukherjee's popular films have only been buggered lately with big-budget remakes—Khubsoorat (with Sonam Kapoor), Bol Bachchan (Rohit Shetty's version of Gol Maal), Aashiqui 2 (what was it, if not Abhimaan). In that context, a book such as Singh's is a fine #ThrowbackThursday to Hrishida's empathetic makaan that so entertainingly presented various rang birangi shades of life, while remaining so minimalistic and simple.

Here are two ways to enjoy this book. One is no different for well-written film reviews that aren't wholly journalistic (collections of Pauline Kael or Roger Ebert, for example). Read it after watching the films. If not, and this is something the author rightly hopes for, the book will inspire you to binge- watch anyway. I intend to start with Shaitani Anand (1980), which I hadn't even heard of. It's Mukherjee's sequel to Anand (1970), in the horror /zombie genre, produced by one Bhootpret Ramsay, where Rajesh Khanna (or Anand) returns from the dead to teach people lessons on death rather than life. What's there not to love about that idea?

(Mayank Shekhar runs the pop- culture website TheW14.com)