Delhi to Hyderabad

IN THE EARLY 18th century, a Mughal courtier, Nizam-ul-Mulk Mir Qamar-ud-Din, was appointed the subedar of the Deccan. On his way south, Nizam-ul-Mulk went to seek the blessings of his spiritual guide, the Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin Aurangabadi. Since Nizam-ul-Mulk was hungry, the saint offered him kulchas wrapped in a yellow cloth. The subedar ate seven kulchas—and the saint blessed him: Nizam-ul-Mulk would be king, and his dynasty would rule for seven generations.

The Asaf Jahi dynasty, of which Nizam-ul-Mulk was the founder, did rule Hyderabad for the next seven generations, and those legendary kulchas, along with the yellow cloth, featured on the Asaf Jahi flag.

A humble association for a state so powerful. In 1947, Hyderabad was not just one of the biggest and most powerful princely states of India; its nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, was the wealthiest man in the world. He considered himself a sovereign ruler, and a sovereign ruler he wished to remain. Bolstering the nizam’s resolution was the rabid Kasim Razvi, who, along with his ragtag militia (the Razakars), embarked on an anti-Hindu, anti-India tirade. At the same time, an opposing camp, consisting of Communists, Congress supporters and others at odds with Razvi, had emerged. Far away in Delhi, while trying to control sectarian violence and resettle refugees, Jawaharlal Nehru, Louis Mountbatten, Vallabhbhai Patel and their colleagues were debating ways to get Hyderabad to accede to India peaceably.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

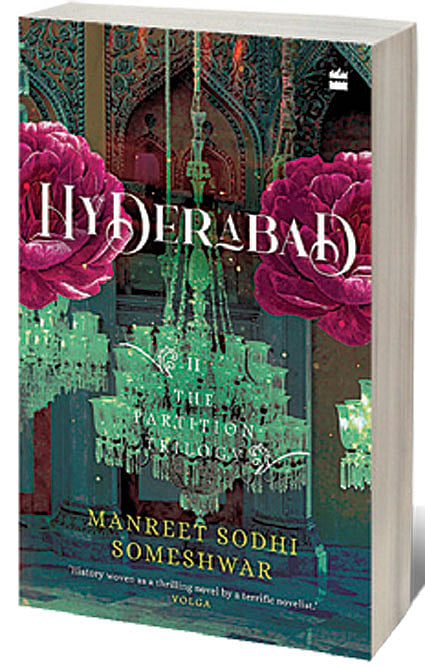

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar’s Hyderabad, the second book of The Partition Trilogy, focuses on this space, this time. The novel, set between July 1947 and September 1948, moves between a large cast of characters, both fictitious and real, divided between Delhi and Hyderabad.

In Delhi, there are mostly the real people, the statesmen trying to bring about an amicable settlement with Hyderabad: Mountbatten, now readying to return to England; Nehru and Patel, their differences cropping up at a time when their unity is paramount; Mahatma Gandhi, trying to keep the flag of ahimsa flying. In Hyderabad, there is the nizam, with a garage full of trucks loaded with treasure, ready to flee. There is the rabble-rousing Kasim Razvi, and the men the nizam has appointed to important posts: the commander-in-chief El Edroos, and Prime Minister Mir Laik Ali. There is the nizam’s Turkish daughter-in-law, Niloufer, bitter but philosophical.

It is in Hyderabad, too, that the fictitious characters of this book are concentrated, almost all as people opposing Razvi. There is Niloufer’s companion and maid, Uzma; the firebrand Jaabili, escaped from a life of gross exploitation to join the leftist Sangham; and the underground pressman, Daniyal, risking life itself to speak the truth. All battling to uphold syncretism and peace in an atmosphere increasingly virulent and bigoted.

Mention ‘Partition’ to the average non-Hyderabadi Indian, and chances are the associations will be of mass exodus, violence and horror along the Pakistan borders. Sodhi Someshwar, with Hyderabad, fills that gap and reveals some of the oft-ignored aspects of Partition. This novel shines the light on the nizam’s Hyderabad, with the tensions and stresses, both political and personal, that tugged it in different directions.

Hyderabad follows a pattern similar to that of Lahore, the first book in The Partition Trilogy: the action switches between Delhi and the other city, between real-life characters and fictitious. Here, however, perhaps because of the convoluted nature of the problem and the larger cast of the characters, there is a markedly greater emphasis on the real, historical people: the Indians and the English trying to solve the knotty issue of Hyderabad’s accession.

The fictitious characters are relatively few here, and though their joys, worries, and politics come through vividly, their stories are not given as much space as those of the real personalities. This does not offer the heart-searing insight that was Lahore; instead, it is an entertaining and fast-paced depiction of Hyderabad in 1947-48. The pain and the fear are there, but they take a back seat to the suspense.