Deepti Naval: The Girl from Ambershire

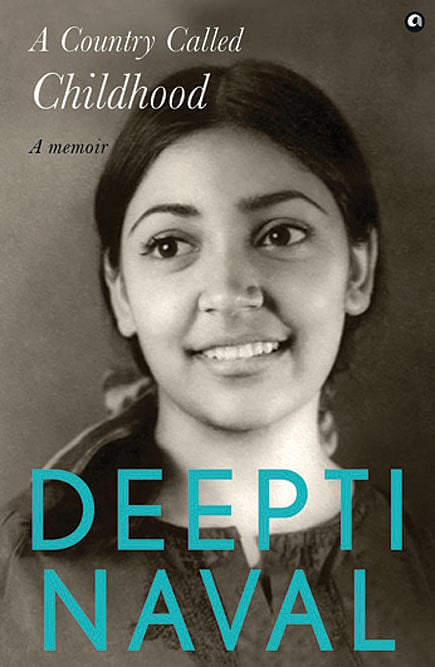

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES, especially by celebrities, usually end up settling scores or setting the record straight. Their literary worth, if any, is limited. Sometimes though, the celebrity is also a writer, a poet, an artist of sublime beauty. The result, A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir (Aleph; 388 pages; ₹ 999), is almost cinematic in its scope and breath-taking in its range. It is a chronicle of its time, a love letter to a city, and a tribute to the parents who raised her, and gave her the security to dream.

But then Deepti Naval has never been a run-of-the-mill celebrity. The star of some of the country’s most beloved movies, from Vinod Pande’s Ek Baar Phir (1980) to Sai Paranjpye’s Chashme Buddoor (1981), Naval has always been as accomplished in writing as she is in acting. A graduate of Hunter College in New York, she found her niche in the offbeat movies of the ’80s with directors such as Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar, the latter perhaps the only person who can get away by calling her “bachchu” (child).

But her memoir is not about her days in the film industry, where she has made 90 movies and counting. Though one hopes a film book will follow as she has already teased us about the existence of meticulously maintained diaries. The memoir is about Amritsar, which the nuns at her school Sacred Heart Convent called “Ambershire”, of the ’50s and ’60s, with its winding lanes and its photo studio where annual family pictures would be shot in black and white; the darzi, where her mother would take patterns from Woman and Home to copy; its rangwala to dye their fabric; its doctor who would administer glycerine to all the kids; its republic of mochistan where shoes would be made; its after-dinner walks where young Naval would wait for a train to pass; and its Chitra Talkies where she’d watch Ben-Hur and The Guns of Navarone. Amritsar, which saw the worst of Partition violence, whose memory was kept alive in family stories of near-death. Amritsar, the city where Naval grew up in a haveli abutting a mosque in an era gone by.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

But the memoir is not about empty nostalgia or cheap sentimentality. It is a love letter to her parents and their secret histories, which she has excavated with patience and compassion, right down to their occasionally ugly altercations, and their ultimate late-age separation. “I’m vague about so many things but everything to do with my childhood is so stark in my mind,” she says. “It’s vivid and it’s not an effort to reproduce anything,” she adds. Perhaps it is a trait she inherited from her mother. As Naval writes in the book, “My childhood was full of stories. These had nothing to do with Indian mythology or stories dawn from the scriptures. There was no Ram for me, no Sita, no Ramayana, no Mahabharat. My mythology was stories of Burma narrated to me by my mother, the nostalgic recreation of her childhood days in the county of her birth.” She would often pull out a photograph to illustrate her stories, picked from a collection she kept safely in a tin box. “My favourite photograph of Mama shows her on a bicycle, in a georgette sari, twice entwined around her waist, her hair is tied in two plaits, and her eyes are covered with black goggles. She is looking into the camera,” she writes.

This book has involved tremendous research and fact-checking, which Naval completed by giving up many roles, many invites to social functions and family get-togethers. She still managed to squeeze in some work, a film with Kalki Koechlin, Goldfish, where they play a mother-daughter duo, which is yet to release. “The other day Nitya Mehra (who directed her in a beloved episode of the Amazon Prime Video series Made in Heaven) called me and said I have to do a film with her,” says Naval. We hope she will. The little girl who grew up idolising Meena Kumari, dressing like Sadhana and not speaking for a season like Sharmila Tagore in Anupama, cannot possibly do anything other than acting.

Little by little, Naval reveals to us who she was as a little girl, living in a kind of alternative reality, sometimes recounting events as they played out in her mind, rather than in actuality. Memory is a tricky thing, always playing hide-and-seek, sometimes to benign effect, and sometimes malevolently. Relying both on her own recall and that of relatives, the portrait that emerges of her parents is profoundly moving. Her father, whose family saw the bloodshed of Partition first-hand, having tried three businesses, starts teaching English at a local college, but then uproots himself quite ruthlessly to allow his children to make something of themselves. He starts life again as a librarian and a night watchman in New York at the age of 48, eventually becoming a professor of English at the City University. It is about his remarkable parents, who lived together in harmony in private, despite being on opposite sides of the political spectrum. Her paternal grandmother was a Congresswoman, and her paternal grandfather a member of the Jan Sangh, close to Syama Prasad Mookerjee who stayed at their Amritsar home before travelling to Jammu and Kashmir in 1951, where he was arrested, jailed and where he finally died.

Her mother, Winnie, born in Burma but forced to leave the country with her family when the Japanese invaded during the Second World War finds her feet in Amritsar in BC Sanyal’s art studio with co-artists such as Satish Gujral and Amar Nath Sehgal, and in its cultural environment with the great actor Achala Sachdev, the Buddhist monk and Kabir Bedi’s mother, Freda Bedi, and the musician Sheila Bhatia. Half a million Indians fled Burma then, walking for weeks through the jungles of Manipur and Assam to cross over to India. Her mother was from one such family and would always miss her days in Burma, having to wait till 2001 to make a return trip thanks to Naval. Winnie was a woman of impeccable taste, made beautiful things, from a new sweater every winter for every family member, to handmade Roman slippers to match the colour of her saree when she taught at the local college.

Her mother was a new kind of modern Indian woman, educated in the fine arts but also in the fine art of running a home, always stretching the family budget for a special treat for the children, whether it was new dresses for Diwali, or a new film with child star Daisy Irani. Her father was the modern Indian man, making his way in a new republic but not tolerating the ugly shape it would take—one of the reasons he decides to emigrate is when his friend from college is bullied by a student he fails. He is garlanded with shoes, made to ride a donkey and flogged through the narrow streets, accompanied by the beating of drums. “The night, Guruan di Nagri, the city of gurus, was shocked into silence. Only the last train could be heard, chugging past the Railway Bridge. Never could one imagine a more ruthless act, a sadder sight,” writes Naval.

Her parents were her heroes. “I admired their togetherness,” she writes. “Mama and Piti (short for Pitaji) would often sit out in the sunlit veranda, discussing Byron and Keats at the dining table, and sharing their views on life. I thought if there was companionship, it should be this,” she writes.

THERE ARE PASSAGES of acute heartbreak written exquisitely, from her maternal grandmother’s exodus from Burma with the family gramophone on her back, to her mother’s three lost babies, among them a boy who lived till he was eight months old. There are also accounts of her own embarrassing deeds, the worst of which is the day she runs away from home at 13 because she wants to see the mountains, the result of watching one too many films in the mid-sixties set in Kashmir. She survives that, despite the threat of a molestation, but not before the fright of her life. She also recounts her first kiss, with a girl, who was first institutionalised by her family and who then died tragically, unable to live with her schizophrenia.

There are her friends, her seniors (among them police officer Kiran Bedi and theatre director Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry), and her teachers, mostly nuns, whom she wanted to emulate. And there is her ambition. At one point she engraves the whitewashed pillar of the veranda with a knitting needle, her address: “Deepti Naval, Chandraavali, Katra Sher Singh, Hall Bazaar, Amritsar, India, World, Universe, Cosmos, Space.” This is what her father sees by chance upon returning from his first visit to America in 1961. She writes: “Years later, in America, he told me that it was when he read my writing on the pillar, that he had made up his mind to leave Amritsar, emigrate to the US, and provide for his children a wider stage on which to enact their lives.”

There is lyricism in the writing, in describing even the most mundane details, such as lighting candles on Diwali: “I loved the feel of candles, tilting each one to let the melting wax drip on to the concrete edge and then placing the flat end of the candle carefully into the warm wax to hold it upright.” There is a conversational quality which makes it seem like a long storytelling session with a close friend, full of confidences, good laughs and even more satisfying weepathons. And there is also a touch of the surreal in the hat stand with the mirror that Naval would talk to: “The hat stand stood there, with the patience of saints, taking into account each flickering indication of bloom on my face, the first flush of youth, recording each moment of doubt, anxiety, disappointment, and joy.” Years later when the Amritsar house was demolished she let go of everything else except the hat stand, and it stands today framed by snow peaks in her little art studio in Himachal.

Against the backdrop of a newly independent India learning slowly to live with the betrayal of friendly nations and work out vengeance with old, unfinished enemies, Naval also speaks to us of a past that is gone—the washing of brass dishes with ash, the elaborate cleaning of ear wax, games such as buntae and stapoo, much loved buffaloes with names; and typing classes before going to America. “I wanted to recreate my world for the reader the way I had lived it in my mind,” says Naval, now a sprightly 70.

She started the process of writing the memoir five years ago, sending the first four chapters to Aleph co-founder David Davidar. She had sent him some poetry a few years ago which he didn’t seem too keen on, but then with the memoir, she got a call the next day at 7.45 am. She knew it would not be a rejection. Her serious work began then, there were so many jottings, multiple notes scattered all over the place. Everything required recording, researching, checking. “I wanted to do this to pay homage to my parents for giving me a childhood that was so precious. Both are gone now but they knew I was working on this,” she says.

They would be proud of their little Deepi, their nickname for her.

For in writing of them she has also understood herself. As she writes: “I have spent the last forty years of my career as an actress thinking that I’m a misfit in the Bombay film industry, that I come from an academic background and have nothing to do with show business. But I had no idea that cinema has been in my blood. It is in my genes—between my grandfather’s three little boxes reserved in three cinema halls, my Mama’s stunning black-and-white photographs of Bette Davis and Devika Rani and Indu Bhaiya’s stint in the world of films, my destiny had been charted.”

We are the sum of the stories we are told, none more so than Naval. As she writes in the preface: “Stories, I don’t nurture them, they nurture me.”