Curfewed Lives

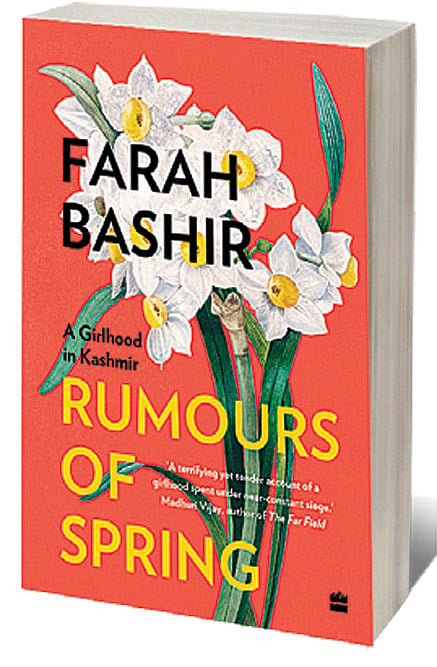

A MIASMA OF VIOLENCE, fear and foreboding hangs heavy in Farah Bashir’s memoir, Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir, a gut-wrenching account of an adolescence spent in the shadow of a siege in one of the world’s most militarised zones. The siege pushes itself into private lives, meddling with their daily rhythm, messing them up. Endemic, invasive and insidious, it seeps into their breath and even alters the aroma of something as essential as tczochvoar (bread).

Woven around a death in the family—of Bobeh, Bashir’s asthmatic grandmother, in the winter of 1994—the memoir chronicles the minutiae of her daily life as she comes of age in the early 1990s, when the insurgency is at its peak. Early in her story, Bashir writes about the sounds of jackboots entering, inch by inch, into the kitchen, overlooking the street, of her five-storeyed house on the busy street of Shehr-e-Khaas (downtown Srinagar) during an evening patrol by the armed forces in 1991. “From there, they stomped on our temples and entered our heads; the marching steeped into our silences, punctuated our conversations with pauses, which, in turn, jumbled our thoughts and our language.”

Like the sounds of military boots, the tear gas, too, enters all homes, “through crevices, gaps, windows ajar, even those that were tightly shut; it entered our rooms and made breathing difficult for the young and laborious for the old,” prompting Bobeh to say: “This zulm (atrocity) is worse than the (Indo-Pak) war of 1965.” And, then, there are the incessant curfews that tame, control everything — not just the movement of the living, but even the last rites of the dead. It leads to schools being shut for months on end and causes endless rescheduling of exams. It governs the household chores and regulates walking, studying and sleeping: “The dreams we dreamt were always at the mercy of someone else, someone occupying us, ruling us.”

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Bashir’s compelling and clear-eyed portrait of Kashmir brings the horror and tragedy of the conflict up close. In the Kashmir of curfewed nights and collaborators, lives hang on prayer and hope — the spectre of death haunts all habitats, besieged by terror and convulsed with impromptu crackdowns. There are firings on unarmed protestors, even on funeral processions. There are explosions, encounters, raids, detentions, custodial killings and unexplained disappearances. Homes are turned into battlegrounds by the troops.

Filling a void in the narratives on Kashmir, Bashir writes affectingly about her period pains and about losing her first love to a burnt post office, the only means of communication between them. During the crippling menstrual pain, she is forced to keep lying in her bed, suffering her pain silently. She does not dare to make any movement, not even to go to the washroom, which entails opening several doors in her large house: “Any sound could attract a volley of bullets fired in your direction.” It is a time riddled with uncertainty and rife with mass killings in grenade blasts.

Phone lines are extremely undependable: “Bas moklyov yi (the line is dead)”. Road links are frequently cut off. And the local newspapers are “mortuaries laid out on broadsheets”. In the climate of mind-numbing violence, when people become statistics, “hidden away in the casualty count,”

Bashir has a strange wish for her family and herself: “To pass on from the world ordinarily to appear in the normal obituaries... not lumped together, thrown into an unnamed, unmarked grave or a ditch; denied the dignity of a proper burial.”

Rumours of Spring is an archive of trauma and psychic wounds that run deep, across generations. It is told gently; it doesn’t veer into sentimentality or collapse under the weight of melancholy. It will tear your heart out with its startling power, ruthless precision and profound emotional force.