Colonial Hauntings

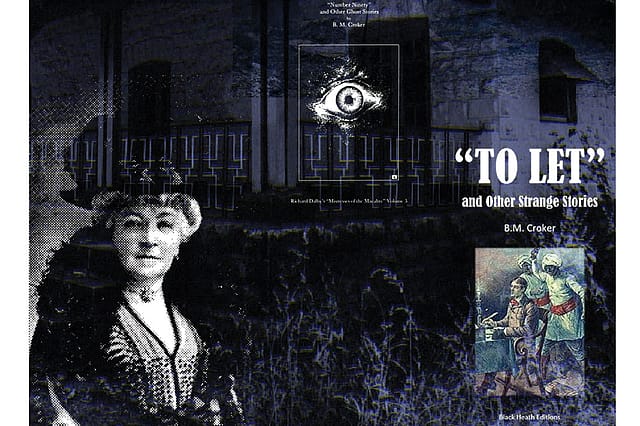

IN 1861, Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management included a recipe for curried fowl and described the distinct Indian flavour of curry powder. The book addressed the concerns of many Englishwomen who were starting their households in India. The memsahibs were sandwiched between making the perfect steak and kidney pie and making the kedgeree Indian enough. They had to strike a balance between maintaining British sanctity and humouring their husbands who had developed tastes for things native. Their lives were both complex and challenging. In order to get a glimpse of these lives, one has to largely depend on literature about domesticity. The Anglo-Indian memsahib occupied a unique sociocultural space. While they had some control over native 'servants', they still had a subservient role in the larger colonial framework. Further, unlike native women, their spatial mobility was also limited. There were things a memsahib could never do, places a memsahib could never go to. These women were in a space of pronounced ambivalence. It is not surprising that ghost stories helped them document their inconsistent situation in India. Bithia Mary Croker (1848-1920) and Alice Perrin (1867-1934) wrote many stories about their lives and experiences in India. They are best known for their ghost stories.

Literary historian Melissa Edmundson Makala maintains that through their spooky tales, both Crocker and Perrin were trying to continually understand and negotiate their social position in the colonised world. Their storytelling styles are rather inimitable. Unlike their male counterparts, they described India with a feminine eye. For example, in her short story ''To Let'', Croker describes the journey from the plains to the hills in Indian summer: 'A long journey in India is a serious business when the party comprises two ladies, two children, two ayahs and five other servants, three fox terriers, a mongoose and a Persian cat—all these animals going to the hills for the benefit of their health—not to speak of a ton of luggage, including crockery and lamps, a cottage piano, a goat and a pony. Aggie and I, the children, one ayah, two terriers, the cat and mongoose, our bedding and pillows, the tiffin basket and ice basket, were all stowed into one compartment, and I must confess that the journey was truly miserable.' In fact, most of their stories involved either difficult journeys or them trapped in haunted houses. One can clearly see that their lives directly impacted their imaginations.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Although, most of Croker's stories featured women making independent journeys, Perrin's stories were often about meek and submissive wives whose journeys were always monitored by their husbands. Her characters were often lost in forests, trapped in native crowds or trapped in their own houses by the fear of their husbands or the unknown native. But like Crocker, Perrin too had a vivid style when describing India. She described a platform in north India where a train from Bombay had arrived in this way: '[The platform] instantly became covered with struggling yellow mass of natives: fat, half-naked merchants; consequential Bengali clerks, with shiny yellow skins and lank black locks; swaggering sepoys on leave, with jaunty caps and fiercely curled beards; keen hawk-faced Afghans wrapped in garments suggestive of Scriptures; whole parties of excited villagers, bound for some pilgrim shrine, clinging to each other and shouting discordantly; refreshment sellers screaming their wares, and coolies, bearing luggage on their heads, vociferating as wildly as though their lives depended on penetrating the crowd' ('A Perverted Punishment').

Scholars and other writers like Ruskin Bond have pointed out that both Croker and Perrin seemed to have way more compassion for natives than their English male counterparts. Since their interaction with Indians was on a different level than that of English men, they saw India differently. Perrin even said she was deeply interested in Indian religions and histories. Yet all her stories clearly indicate fear and mistrust of natives. I do not doubt Perrin's genuine interest in India but, at the same time, her work is an excellent indication of the conflicted feelings of a memsahib. For example, in 'An Eastern Echo', the whole drama unfolds when natives start a riot during Muharram and a British officer saves the White woman in distress. Many years later, the officer's ghost visits her when, once again, natives riot during Muharram and he dies trying to stop them. In 'Chuniya, Ayah', the competent, trustworthy ayah is reprimanded. In her anger and desire for revenge, she kills her ward whom she loves deeply. Chuniya is not suspected of the crime; it is considered an accident. Eventually, the guilt drives her insane and she ends up in an asylum. In another story, titled 'The Belief of Bhagwan, Bearer', we meet Chumpa, the native woman oppressed by her husband. She accidentally kills him but his ghost comes back to haunt her. In Perrin's stories, natives are either on the periphery or are unreliable. They are also shown as irrational and infantile. Like many Victorian ghost-story writers, Perrin, too, utilised the trope of exoticising natives as possessors of magical powers. In 'Caulfield's Crime', we meet a shape-shifting fakir who takes the form of a jackal and punishes the cruel White man who refuses to follow the rules of the swamplands.

Croker's relationship with natives was much more intimate than Perrin's. The former's stories gave natives far more agency, even though there were obvious signs of mistrust. Croker clearly showed compassion for native women. In 'If You See Her Face', we meet the ghost of a nautch girl who kills brutal and unjust men. Two British officers come to a very poor village. When the villagers beg for food, the older officer beats them. The younger officer, however, talks to them kindly and even gives them money. He is then warned of the dangers he will encounter in the hunting lodge which was once part of the king's palace. The young man escapes the wrath of the ghost simply because he respects local beliefs and shows kindness towards the poor. But like Perrin, Croker also exhibited ambivalence towards India and its people. In 'The Khitmatgar', the ghost of a cruel server carrying a tray of drinks haunts a bungalow. Anyone who accepts the drink will die. There is no back story for the ghost; he is just a malicious, evil spirit. Similarly, in 'The Dâk Bungalow at Dakor', two memsahibs witness a spectral event involving the murder of a British officer by his servant, who first slashes the officer's throat and then steals all his money. This takes place against the backdrop of the 1857 revolt. Further, Croker's stories featured Victorian staples like superstitious natives, foolish Indian servants, incompetent nursemaids and so on.

When it comes to giving the memsahib some sort of an identity, we notice a sharp difference between the two writers. Perrin's characters are frequently afraid and submissive, while Croker's women are vivacious, brave and independent. Croker's women travel alone to forests, manage their households independently, exhibit clear ambition for social mobility and are largely unafraid of their husbands. Perrin's, however, are deeply afraid of the sahibs. In one of her powerful stories called 'A Man's Theory', the oppressive man stops his timid wife from attending to their desperately wailing baby to make their son strong. Once the crying stops, we discover the child is dead, mauled by a huge rat. Again, in 'The Tiger-Charm', we encounter an elderly, cruel husband who falsely accuses his wife of having an affair and then almost kills her friend in a shooting accident. However, the friend is saved because the wife had secured a native amulet for him that would help protect him from the tiger—the tiger kills the husband instead.

Like most British writers of that period, Croker and Perrin showed a deep fascination with the jungle. Spooky encounters often happen in the forest and there is endless enthralment with man-eating tigers. There is always a hunting lodge or an unkempt dak bungalow where terrifying events unfold. It would be unfair, though, to accuse Croker and Perrin of sticking to ghost-story clichés. Perrin evoked fear effectively just by describing the surroundings. In 'The Fakir's Island', an Englishman is horrified that a memsahib wants to see Indian holy men: '[They have] fierce, fanatical faces, the hideous deformities, the lack of clothing on most of the holy men, and the evil attention that the presence of a young English girl attracts in such a crowd.' Later in the story, the memsahib defies her fiancé and visits the holy men, only to come back and catch smallpox and look hideous for the rest of her life. She is punished for her defiance and transgression of the borders between the colonisers and the colonised.

The fear of being tarnished by native men is strongly voiced by both writers. They are continuously afraid of Brown men violating them, murdering them and stealing their belongings. But we also find elderly and kind Brown men who are happy to help and serve their memsahibs. Naturally, spaces that had a large number of Brown males automatically became hostile and dangerous spaces.

The key feature of Anglo-Indian, female, ghost-story writers is their ambivalence. True, even male writers exhibited that, but women articulated it differently. They brought domestic concerns to the forefront. Leaving their child in the care of the native ayah bothered British women. At the same time, they also showed compassion for nautch girls and female domestic servants. We see them comparing their own marital relationships with those of native women. On the one hand, they saw Indian women being oppressed by their husbands; on the other, they often felt stifled by their duties of managing large households and their lack of freedom to go anywhere they wanted. White men either terrified them or rescued them from dangers.

Simon Hay, in his book A History of the Modern British Ghost Story, argues that ghost stories were also a method of establishing colonialism. The British still maintained their presence in Gothic structures and refused to fade away from the cultural memory. The ghosts of the Raj still thrive. Warren Hastings is still looking for his papers in Hastings House, Kolkata. Major Burton, killed in 1857, still slaps disobedient servants in Brij Bhawan Palace Hotel. Colonel Webster's headless ghost still tries to protect Fatehpur. And every old villa in Shimla still houses numerous British spirits. Meanwhile, the ghosts of memsahibs perhaps lurk in the kitchen, feeling deep remorse when cooks put too much chilli in their food.