‘You Can Hide the Most Powerful Gunpowder Within Language’

Malayalam author and screenwriter, Unni R uses satire and subtlety to talk about contemporary India. The author in conversation with Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

|

05 Oct, 2020

|

05 Oct, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Unni-R2.jpg)

Unni R

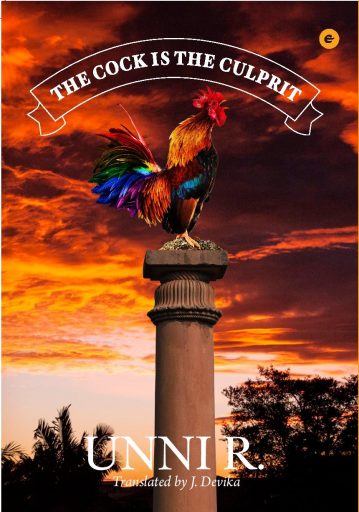

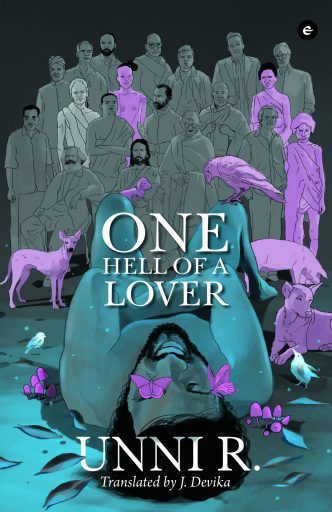

Unni R is a well-known figure in Kerala’s literary and film circles. His two recent works—a short story collection, and a novel—translated for the first time into English One Hell of a Lover and The Cock is the Culprit have given English readers the privilege of knowing him. Both books have been published by Eka and translated by J Devika. The Cock is the Culprit is a finely crafted parable for modern times. The 49-year-old, Thiruvananthapuram-based author speaks about the books of his youth, challenges of the novel form (why The Cock is the Culprit is not a novella) and the ‘filth in society’s eyes’ today. Excerpts from the interview:

Can you describe the view outside your window? What are the sounds you hear? The views you see?

This question delights and fascinates me at the same time. I have often wondered whether any interviewer would ask me about the view beyond my windows. That’s why it delights me. While I was reading the book Windows of the World; 50 Writers, 50 Views edited by Matteo Pericoli, my eyes would often wander from the book and find a place near the window to look out. Beyond my window is a wide swathe of land unencumbered by construction. My window opens onto this green expanse, filled with coconut trees, mango trees and other vegetation. Occasionally I spot the owner of the land walking through the plot with a stick that appears weaker than his body. It feels as if his whole courage is vested in this stick. Parrots, crows, kites, crow-pheasants, mongoose, chameleons and snakes are guests who come to this space, and I can hear birds chirping through the day. But I notice that the cawing of crows has lessened over the years. I’m sure the birds see me too, and my window is the barred expanse through which our looks connect. Since a few days, my fan has lost control of its sanity and has been making itself heard above the sounds outside the window. One of my friends who calls me often asks me if I am sitting in a weaver’s room. In a way, isn’t this a weaver’s room?

What were some of the first stories you wrote? What pushed you towards writing?

The earthen wall behind my house was also the boundary of the Kudamaloor Govt. High School [in Kottayam district, Kerala]. School anniversary celebrations usually included Absurdist plays. These featured in competitions too and resonated deeply with me. I ended up writing plays that were incomprehensible even to myself. I still remember that one of them was about the caretaker of a cemetery, and it had the soul of one of the numerous plays I had seen. I transitioned from scrawling dramas in pencil on double-line notebooks to writing stories, in tenth grade, when I wrote for the school magazine. The desire to be a writer was in me right from childhood. But I had misconceived writing as an escape, or as a profession for somebody who was not good in studies.

What are your earliest memories of reading?

I didn’t have a reading culture at home. We subscribed to the newspaper, and to the popular Malayalam weekly Manorajyam for Amma and Ammumma. However, the reader in me was only interested in Balarama, the children’s magazine that appeared regularly in my friend’s house next door, which he used to keep hidden. He allowed me to read it only under his strict supervision. I was never allowed to take it home. He hovered around me like a policeman watching a prisoner whenever it was in my hands, and each time he would snatch it away before I finished reading. Perhaps it was this yearning for a forbidden fruit that spurred me to go in search of books. In those days, Sovietland was a regular feature at home and I would flip through it for the pictures that introduced a whole new world for me. Textbooks were covered using those pages and when the Soviet Union disintegrated, I was most saddened by the loss of covering material for children. Yet another interesting thing at home was a book that Achchan had bought for 75 paise. It had exquisite pages. I tried reading it, but the first line left me shaken and unsettled. I was so fascinated by the book that I carried it to school every day. When I grew up, I realised that the book was the Communist Manifesto, the spectre that had stirred up the world. These intriguing external factors have certainly influenced my reading. That’s how I became a member of the local library, where I tried reading OV Vijayan and Paul Zachariah, among others. It was when I read Khasakkinte Ithihasam [Legend of Khasak] at a later stage that I realised how much of a failure my initial attempts in reading were. Nevertheless, the books that I tried reading during my initial days as an uninformed reader, welcomed me wholeheartedly when I read them again.

In the present political situation, we see that those ‘sacrificed’ are primarily women, secondly Dalits and thirdly activists and writers. Our society is not only patriarchal, but it’s also witnessing the growth of a new kind of fascism in it. Fascism is a male doctrine

It is often said that short stories are far harder to write than novels. Having started with short stories, would you agree with that? What drove you towards writing a novel (a novella, to be precise)? What have been the challenges with this form?

Short stories and novels have their own unique challenges. Short story writers need to have the finesse of a hunter on the prowl. They have to be precise. A novel on the other hand holds the possibility of movement. Both genres create two different kinds of worlds in writing. Questions of form, language, and point of beginning are all decisions that the writer has to make every time, and he has to essentially make them himself. Perhaps it’s the joy he gets from dealing with these complexities that makes him come back repeatedly for more.

My novel The Cock is the Culprit should not be mistaken for a novella based merely on its length. The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Alessandro Baricco’s Silk are both great novels that are less than 100 pages. Books should not be differentiated based purely on their size. I have written a novel and it should be seen as one.

Could you tell us a bit about the sketches in the book?

Riyas Komu is a brilliant artist and sculptor and also the co-founder of the Kochi Muziris Biennale. His works on Gandhi, Ambedkar, and his Ambedkar sculpture are renowned works of art. Moreover, his efforts to conduct a political discourse through his work is something that has always captivated me. The rooster crowing on top of the Ashoka Pillar, and Riyas’ interpretative illustrations in the novel has definitely enriched it.

In what ways do you think Kerala informs your fiction?

Kerala has a vast literary tradition. A strong political tradition. I get the seeds of a thousand stories from this soil. Kerala also has deep gender and caste divides permeating society. Although the state lays claim to a strong Communist movement, the Adivasi and Dalit communities are excluded even today. Here, the Leftists are still bound by the sacred thread of Brahminical consciousness. A writer has only to keep a vigilant eye on this land and its people who act liberal yet remain deeply conservative. The journey to my novel started with the disturbing news of the death of a young Maoist called Jaleel, in Wayanad. Who gives anyone the right to take away a life? I do not subscribe to Jaleel’s political beliefs. However, when such an act is justified by a Communist chief minister who is also in charge of the police, in his capacity as the Home minister, one wonders how primitive Kerala really is.

In The Cock is the Culprit, characters at times suffer for no fault of theirs. You write, ‘Naaniyamma became irrelevant before the glory of the nation.’ How do you understand the term ‘glory of the nation’?

In an ideal scenario, a glorious nation would be one that is committed to democratic values like equality, freedom and dignity for all. Yet, in reality we witness how the achievements of a nation are increasingly being measured in terms of its military strength, its economic growth rate or the number of billionaires it has. Consequently, the lives of ordinary citizens like poor farmers, Dalit women or migrant workers are valued less than the lives of rich industrialists or political elites. Gender too plays a role here. If you observe, it’s always the visible acts of valour by men especially in wars that are celebrated as performances of heroism and patriotism while everyday acts of bravery, integrity, sacrifice and altruism by women are never gloried.

Writers, by weaving in elements of time and location into their writing, are creating a parallel world. They can be viewed as the Little Gods of these worlds. Today the State and religions fear even this imaginary world

In One Hell of a Lover, roosters make an appearance in the form of Vladimir and Bukharin. What according to you is the biography of a rooster?

Vladimir and Bukharin, the two roosters make an appearance in the story Satanic Verses. Bukharin was a Politburo member who was killed during Stalin’s rule. This very same Stalin had misbehaved with Vladimir Lenin’s wife, and Lenin’s letter demanding his apology came to light during Khrushchev’s time. I have felt that a rooster can be used as a metaphor for anything that’s sacrificed in an autocracy or in fact anything that’s totally prohibited in such times. Autocrats fear screams, and their only solution to it is annihilation. I prefer to write the biography of a cock that crows bravely, rather than write about a rooster who suppresses his voice. Maybe that’s why I wrote this novel.

Why do you think it is important to write tales? What is the place of a fiction writer today?

I think there’s a storyteller in every human being. When we relate an incident to another person, elements of our imagination creep into that description. We are recollecting an experience. The language of that recollection is often similar to that of storytelling. But writers, by weaving in elements of time and location into their writing, are creating a parallel world. They can be viewed as the Little Gods of these worlds. Today the State and religions fear even this imaginary world. That’s the reason Salman Rushdie could not attend the Jaipur Literature Festival. You can hide the most powerful gunpowder, very securely, within language. The State is aware of this and hence writers are jailed and killed. Every story is a lie. But if you look closely you can smell the truth hidden in these stories.

You write about the ‘nercha-cock’ or the sacrificial cock. Today we often see the phenomenon of a scapegoat (Rhea Chakravarthy, for example) someone who is sacrificed to divert attention from something else. What do you think of the ‘scape goat’ in today’s society?

In the present political situation, we see that those ‘sacrificed’ are primarily women, secondly Dalits and thirdly activists and writers. Our society is not only patriarchal, but it’s also witnessing the growth of a new kind of fascism in it. Fascism is a male doctrine. And as a result, it is only natural that women are preyed upon. Dalits, writers, and activists are the unorganised sections of society. It’s easy to kill them or lock them up in jails. The media pants greedily around Rhea Chakravarthy with mikes resembling obscene penises. When an actress gets more attention than Sanjay Dutt ever received, we realise how much filth has accumulated in society’s eyes today.

Short stories and novels have their own unique challenges. Short story writers need to have the finesse of a hunter on the prowl. They have to be precise. A novel on the other hand holds the possibility of movement

You write, ‘Many acts of injustice are carried out for a ‘good cause—for the country’. What do you make of these ‘good causes’?

We can talk about these good causes only after placing them within inverted commas. We have several instances to prove that any harm could be perpetrated in the name of the country. We can name anyone as a traitor without any proof, or we could make them all terrorists. This should not happen in a democratic country. Many writers write with fear today. They apply self-censorship in their writings. They are afraid that misreading of a word or a sentence could turn them into a traitor. We have heard the demand to send people like UR Ananthamurthy to Pakistan because they had something different to say. Those who claim that these are all for the good of the nation are trying to bring about a monolithic culture erasing the multicultural diversity of lives in India.

‘Chaakku drew upon his own experiences to prove that if someone fritters away an occasion to prove their love for the nation, there must be deep anti-national sentiment piled up high inside them,’ you write in The Cock is the Culprit. How do you understand the term ‘anti-national’? And how do you think people use that term today?

To me a patriot and a nationalist is one who abides by the spirit of the Constitution of India. An anti-national is one who dismantles, disrespects and disobeys this idea of India as envisioned by the makers of our Constitution. However, today we live in a New India where the rules of the game are completely redefined. Big and small efforts are made to create a single nationalist identity by erasing local histories. Anyone who questions the majoritarian government or stands up for the rights of those who are placed at the margins would be called an anti-national today.

Why is satire an effective tool to write about life today?

Satire is a form used by writers not only today but at all times, particularly under totalitarian rule. Kunjan Nambiar, the 18th century Malayalam poet had spoken up against the king’s rule and other questionable practices in society through the language of satire. In today’s scenario, in this post-truth period, the potential of satire is immense. In my novel I have tried to combine aspects of satire as well as folk tales.

How do you spend your time when you are not writing?

I believe that writing happens even when one is not with pen and paper. For me, the act of writing continues even after I am physically done with it. It happens within me during those tiny intervals between my reading, movie watching and playing. I have written very little in these long years, yet I write ceaselessly.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba