Breaking Barriers

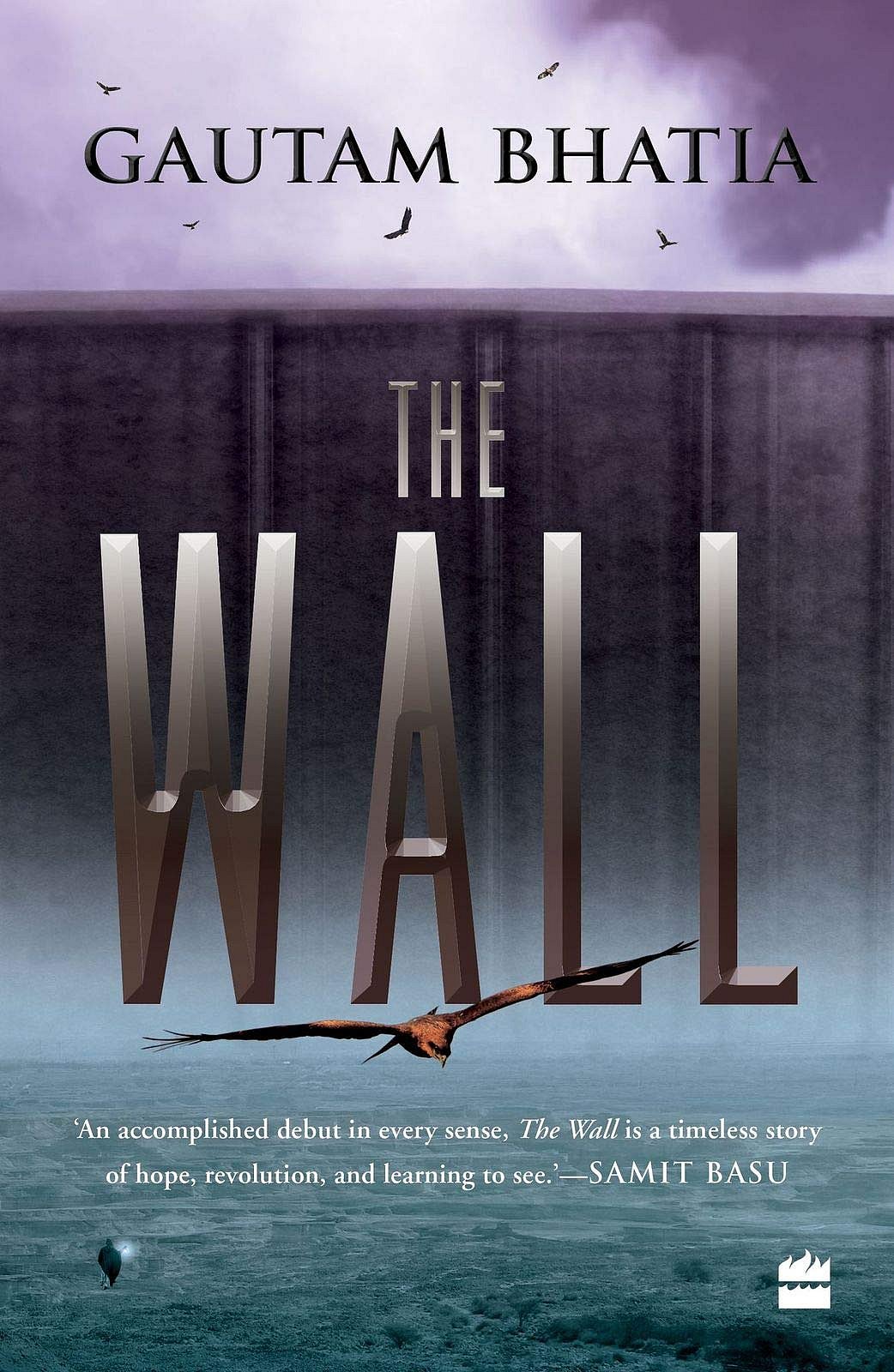

The act of reading Gautam Bhatia’s debut novel, The Wall, feels a little like hitting the ground running. There is no gentle introduction for the reader, who is dropped right into the midst of an escape attempt gone wrong. As the pages turn, the names fly at you—Alvar, Garuda, Mithila, Mandalas—leading to some confusion and much consultation of the cast of characters and the detailed map provided at the beginning.

But the reader’s effort is soon rewarded when Bhatia’s narrative begins to open up, layer by layer, to display an intricate world where faith and reason argue with each other.

In Sumer, most people believe that the enormous Wall that encloses their city is a punishment imposed by a god-like group called the Builders, for a transgression committed 2,000 years ago. No one can enter or leave Sumer except the garudas who routinely fly overhead. Like the ancient civilisation of Mesopotamia, the fictional Sumer too has impressive architecture and a powerful priesthood, the Shoortans, who claim to be intermediaries between the people and the Builders. While there are no easy parallels to our world, Sumer is bound by a rigid class structure which also has similarities to the caste system—your status and occupation depend on where you are born. In a city with little upward mobility, lucky are those born in the first Five Circles, closest to the seat of power—they live in the best part of the city, own the means of production and head Sumer’s version of a government. Those from the remaining 10 Circles make do with limited resources and dreams.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Speculative fiction can sometimes be intimidating for new readers, especially when compared with the familiarity of realism. Committing to an entirely new fictional world where you have to figure out the rules as you go can feel exhausting. But The Wall is an example of why it’s important for those unfamiliar with the genre to take the plunge—at a time when governments are happy to erect more barriers and clamp down on dissent. Bhatia and his heroine, Mithila, remind the reader why unfair notions must be challenged, even if it means inviting the wrath of the powerful.

Early in the book, Mithila is described by someone she briefly meets as ‘that troublemaker who goes around protesting against the Wall’. That’s an apt summary of this extraordinary character who is defined only by the purpose she seeks to achieve—bringing down the Wall. She’s not quiet about it either, preferring to speak her truth even when it would be safer to conform. Born in the Seventh Circle, Mithila is training to be a singer, but her obsession is the Wall. She leads a group of young people who dream of a day when their imagination is no longer curtailed by a solid structure that cuts off the horizon. She is also in love with the daughter of one of Sumer’s most powerful men.

Sumer is oddly progressive in some ways when compared with the contemporary world. The relationship between Mithila and Rama is not just accepted, it’s described as the ‘pure union’. Instead, heterosexual relationships, especially between those from different Circles, can face hurdles, mainly because they may add to the population (a big challenge for a city that no one can leave). Apart from Mithila, there are plenty of other powerful women characters. While Sumer has plenty of problems, it seems, at least from this book, that patriarchy is not one of them.

One of the few flaws of the book is that we rarely see the impulses that drive the other characters. However, even the villains are given some depth and complexity, and the highlight is a courtroom scene where people both for and against the Wall outline their arguments.

The political questions raised by The Wall are crucial, and it is hard to put down once you get past the initial disorientation. The pace picks up especially towards the end, racing towards a heart-pounding climax that guarantees readers will impatiently await the sequel.

In the meantime, I know I’ll keep thinking about Mithila’s biggest reason for doing what she does: sometimes, a Wall has to come down just because it exists.