Between Cricket and Cancer

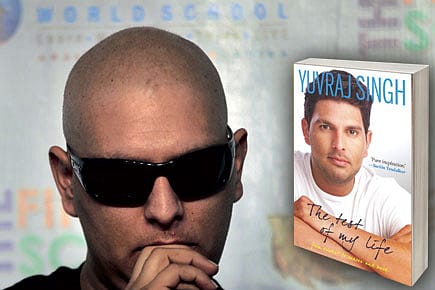

Yuvraj Singh's account of how he got into the game and battled cancer is a surprisingly engaging read

Before you begin The Test of My Life by Yuvraj Singh, there is the question of what exactly it will contain. Much of Yuvraj's life has been ever-present on the sports pages over the last decade. There are also many books on surviving cancer, and, unlike say Lance Armstrong who wrote It's Not About the Bike, Yuvraj's cancer was no touch-and-go affair. It was known to be treatable. When you see a list of sponsors in the acknowledgements section, you are prepared to keep expectations at ground level. Then there is a short prologue of how he made a drowsy prayer to God about paying any price as long as India got the World Cup, and you anticipate cheesy melodrama. As it turns out, the book is a page-turner told in a no- frills manner with a tinge of humour. You probably have to give some credit for that to his co-authors—Sharda Ugra, one of India's best sports writers, and Nishant Arora, a former sports journalist turned manager of Yuvraj.

Once the first chapter starts and Yuvraj starts talking about his father's manic and often brutal obsession with making him a cricketer, the book jumps to life. Some of the stories are known, but in its first-person details, it is riveting. Take his life as a kid. He once broke an expensive racket in anger after losing a match. He writes, 'Back then I had started thinking of my dad as 'Sher', Tiger. I knew Sher was going to give me the shouting of my life—if not a proper hiding, which I had received many times before—and that it would be the end of my tryst with tennis. That is exactly what happened and this is how I stopped playing tennis.' His father once took him to Navjot Singh Sidhu to get an appraisal of his cricketing skills. Sidhu told him there was no hope for Yuvraj as a cicketer. His father told Yuvraj, "Apna basta utha aur ghar chal. Ab main dekhta hoon ki tu cricket kaise nahin khelta." (Pack your stuff, we are going home. I'll see how you don't play cricket.) 'With these words he sealed my fate.' His father personally put him through a gruelling practice regimen with just half an hour a day to catch up with friends. When he got out skying a ball in a Ranji practice match, his father threw a glass full of milk at him. He then told him that if he had not been his son, he would have shot him.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

All this is written almost without emotion. But because of his father, he says, and his parents' deteriorating relationship at home, he turned to cricket partly as an escape.

When it comes to the part about his cancer, the story keeps you hooked because he describes his denial of the ailment. There were clear signs as far back as the ODI World Cup. He takes you through game after game in the tournament, detailing how the cancer was making itself apparent and how he was ignoring it. On the morning of the South Africa match in Nagpur, he was vomiting all that he ate. 'I could not eat a thing. Guys around me thought I was nervous. I believed it too. After all, I knew I was a nervous batsman. But throwing up before an innings was taking it to a whole new level even for me.' Two days before the next match with West Indies, he vomited and saw blood in it. While fielding during the match, he kept throwing up so often that the umpire asked him if he wanted to go off the field. And in the final, he had 'fortified' himself 'by eating a lot of sweet bread to keep my sugar levels up and to keep the food down but I didn't feel too high on energy'.

When a chance X-ray showed an entire lung cloudy, it forced him to take a test for cancer, which it confirmed. And even then, in his fear and determination to keep playing, he opted for acupuncture instead of proper treatment. In the second half, the book loses pace when it goes entirely off cricket to cancer and his treatment in the United States. But even then, you are a little startled at the loneliness that a disease can thrust on a public figure like him. Besides his mother and a couple of friends by his side, the picture is of a lonely man wading through gloom. There are a lot of thank-yous spread across the pages. These are a minor irritant. The book works best when he is describing events. Where it gets introspective or spiritual, it drags somewhat. The Test of My Life is an honest account that is worth reading.