Babur’s Soul

The Mughal emperor not only established an extraordinary dynasty and set the tone for their future political, economic, aesthetic and humanistic triumphs, he also produced one of the most fascinating autobiographies ever written to record exactly how he did it

William Dalrymple

William Dalrymple

William Dalrymple

William Dalrymple

|

06 Nov, 2020

|

06 Nov, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Babur1.jpg)

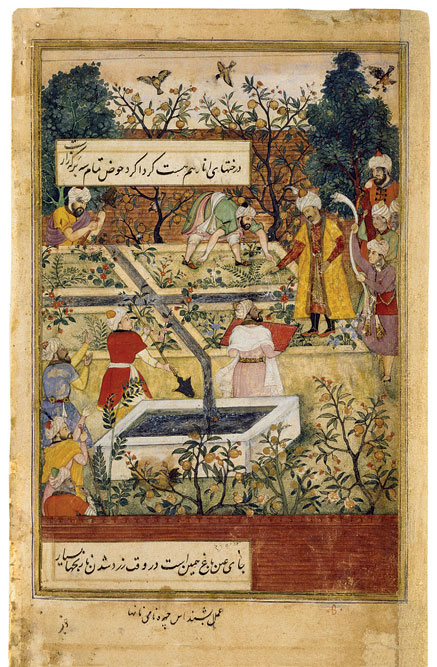

Babur receiving a visitor, folio from a Baburnama edition (c 1590) (Photo Courtesy: The MET Museum)

IN 1526, Zahir-ud-Din Babur, a young Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of handpicked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannon seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital in Agra.

This was not Babur’s first conquest. He had spent much of his youth throneless, living with his companions from day to day, rustling sheep and stealing food. Occasionally he would capture a town—he was 14 when he first took Samarkand and held it for four months. Aged 23, he finally managed to seize and secure Kabul, and it was this Afghan base that became the springboard for his later conquest of India. But before this he had lived for years in a tent, displaced and dispossessed, a peripatetic existence that had little appeal to him. ‘It passed through my mind,’ he wrote, ‘that to wander from mountain to mountain, homeless and helpless, has little to recommend it.’

Babur died in 1530, only four years after his arrival in India and before he could properly consolidate his new conquests. He regarded himself as a failure for having lost his family lands in Central Asia and was profoundly ashamed that his generation of Timurids, thanks to their squabbles and rivalries, had failed to defend their ancestral inheritance after holding Oxiana for more than a century.

He could not have imagined that within a few years, his new Indian conquests would have grown to be the greatest and most populous of all Muslim-ruled empires, with around 150 million subjects—five times the number ruled by their only rivals, the Ottomans. Before long, his family’s new conquests were producing about a quarter of all global manufacturing: by 1650, the Mughal Empire was the world’s industrial powerhouse and its greatest producer of manufactured textiles. In comparison, England then had just 5 per cent of India’s population and was producing under 3 per cent of the world’s manufactured goods. A good proportion of the profits of these Indian manufactures found their way to the Mughal exchequer in Agra, making Babur’s successors, with incomes of around £100 million, by far the richest monarchs in the world.

In Milton’s Paradise Lost, the great Mughal cities of Agra and Lahore are revealed to Adam after the Fall as future wonders of God’s creation. This was no understatement: by the age of Milton, Lahore had grown larger even than Constantinople and, with its two million inhabitants, dwarfed both London and Paris. From the ramparts of the Fort, Babur’s descendants ruled over most of India, all of Pakistan and Bangladesh and great chunks of Afghanistan. Their army was all but invincible; their palaces unparalleled; the domes of their many mosques quite literally glittered with gold. The Mughals were really rivalled only by their Ming counterparts in China. For their grubby contemporaries in the West, stumbling around in their codpieces, Babur’s descendants, dripping in jewels, were the living embodiment of wealth and power—a meaning that has remained impregnated in the word ‘mogul’ ever since.

The Baburnama is the culmination and climax of the Islamic autobiographical tradition as much as the Taj Mahal is the climax of its architectural legacy

If the dynasty Babur founded represented Islamic rule at its most powerful and majestic, it also defined it at its most aesthetically pleasing: this was, after all, the Empire that gave the world Mughal miniatures, Mughal gardens and the spectacular architectural tradition that culminated in the Taj Mahal. The great Mughal emperors were also, with one notable exception, relatively tolerant, pluralistic and eclectic. Their empire was effectively built in coalition with India’s Hindu majority, particularly the Rajputs of Rajasthan, and succeeded as much through conciliation as by war.

This was particularly so of Babur’s grandson, the Emperor Akbar (1542-1605), who issued an edict of universal religious toleration, forbade forcible conversion to Islam and married a succession of Hindu wives. At the same time that Jesuits were being hung, drawn and quartered in London, and when most of Catholic Europe was given over to the Inquisition, in India, Akbar was summoning Jesuits from Goa, as well as Sunnis and Shia Muslims, Hindus of both Shaivite and Vaishnavite persuasions, to come to his palace and debate their understanding of the metaphysical, declaring that ‘no man should be interfered with on account of religion, and anyone is to be allowed to go over to a religion that pleases him’.

Babur not only established this extraordinary dynasty and set the tone for their future political, economic and aesthetic triumphs, he also produced one of the most fascinating autobiographies ever written to record exactly how he did it. The Baburnama does much more than merely keep the memory of his conquests alive. In its pages, Babur opens his soul with a frankness and lack of inhibition comparable to Pepys. Typical is his description of falling in love with an adolescent boy from the Herat bazaar: ‘Before this I had never felt desire for anyone,’ he wrote. ‘But in the throes of love I wandered bareheaded and barefoot around the lanes and the streets and through the gardens and orchards, paying no attention to acquaintances or strangers, oblivious to self and others.’

Throughout his memoir, we are admitted to Babur’s innermost confidence as he examines and questions the world around him. He compares the fruits and animals of India and Afghanistan with as much inquisitiveness as he records his impressions of falling for men or marrying women, or weighing up the differing pleasures of opium, hashish and alcohol. Profoundly honest and unusually articulate, at once emotionally compelling and profoundly revealing, the Baburnama is in many ways an oddly modern text, almost Proustian in its self-awareness. It presents the uncensored fullness of the man, a human life perfectly pinned to the page in simple, direct and unpretentious prose.

The uniqueness of the Baburnama was immediately recognised by all of Babur’s contemporaries as it was by his Mughal successors, who quickly had it translated from Babur’s colloquial Turki to literary Persian; later, in its English editions, it became a favourite text of the Orientalists of the British Raj who had replaced the Mughals in India and who saw many echoes of their life and thoughts in his. According to the Victorian administrator and Persian scholar, Henry Beveridge, the husband of the translator of one volume, Annette Beveridge (and with whom she produced their son William, who was instrumental in the formation of the British welfare state,) the Baburnama ‘is one of those priceless records that is for all time, and is fit to rank with the confessions of St Augustine and Rousseau, and the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton. In Asia it stands alone’.

This last sentence is not quite accurate: there was in fact a wonderfully rich tradition of Islamic autobiography out of which the Baburnama grew and which includes such masterworks as the witty and urbane Memoirs of Usamah Ibn Munquid, a Syrian Arab landowner from the time of the Crusades, and the wise, measured and ironic Mirror for Princes of Kai Ka’us Qabus, the extraordinary 11th century Seljuk prince who built the great Gunbad-i-Qabus tomb tower on the Caspian steppe and had his corpse suspended half way up in a rock crystal coffin. What is true, however, is that the Baburama is the culmination and climax of that Islamic autobiographical tradition as much as the Taj Mahal is the climax of its architectural legacy.

It is not just that the book is so very long and fabulously detailed: it extends to 6oo pages in the latest Turki critical edition, even with 15 Afghan years of the story now missing and lost forever. This means that Babur’s life is more fully documented than that of any figure in the entire pre-colonial Islamic world. What makes it stand out and remain relevant, and moving, today is its universal humanism and its unusual honesty, sensitivity and self-understanding. As his latest scholarly biographer Stephen Dale puts it, ‘Babur transcended the narrative and historical genres of his culture to produce a retrospective self-portrait of the kind that is usually associated with the most stylishly effective European and American autobiographies.’

‘No other author in the Islamic world, or in pre-colonial India or China, offers a comparable autobiographical memoir, a seemingly ingenuous first-person narrative enlivened with self-criticism as well as self-dramatization, and the evocation of universally recognizable human emotions. Not only does Babur make himself engagingly and personally approachable to readers, he also creates a three-dimensional picture of his world otherwise known mainly from stylized political narratives and dazzlingly colourful but two-dimensional miniature painters.’

The Baburnama is also, as generations of readers from different cultures have found, an unusually charming text: a warm-hearted, romantic and deeply engaging record of a highly cultured and honestly self-critical man: ‘His literary work delivers to us everything,’ writes Jean-Paul Roux, the French historian of the Mughals, ‘with his qualities and faults, especially his daily inner self, in his most casual moods, in his most profound thoughts, which often could have been our own.’

From the opening page, Babur’s love of nature and the fineness of his descriptive eye are immediately apparent as he evokes his lost homeland, the Farghana Valley. Passage after passage lovingly describes the things he adored and now, writing in Indian exile, misses: spring mornings spent in hillsides dotted with wild violets, tulips and roses; cold running water, passing through ‘a shady and delightful clover meadow where every passing traveller takes a rest’, ‘beautiful little gardens with almond trees in the orchards’; ‘pomegranates renowned for their excellence… good hunting and fowling… pheasants which grow so surprisingly fat that rumour has it four people could not finish one they were eating with its stew’.

Babur compares the fruits and animals of India and Afghanistan with as much inquisitiveness as he records his impressions of falling for men or marrying women, or weighing up the differing pleasures of opium, hashish and alcohol

Throughout the text, Babur’s eye is alert for natural beauty and inquisitive about its curiosities. He is, for example, delighted by the idea of the flying squirrels that he ‘found in the mountains, an animal larger than a bat and having a curtain like a bat’s wing, between its arms and legs. It is said to fly, downward, from one tree to another… Once we put one to a tree: it clambered up directly and got away but, when people went after it, it spread its wings and came down, without hurt, as if it had flown’.

Whole pages are devoted to the different varieties of many-coloured tulips growing wild in the Hindu Kush or to the smell of Holm Oak when used as winter firewood, ‘blazing less than mastic, but, like it, making a hot fire with plenty of ashes, and a nice smell. It has the peculiarity in burning that when its leafy branches are set alight, they fire up with an amazing sound, blazing and crackling from bottom to top’. He goes into raptures about the changing colours of a flock of geese on the horizon, ‘something as red as the rose of the dawn kept showing and vanishing between the sky’. Elsewhere he rhapsodises about the brilliant colours of an Afghan autumn.

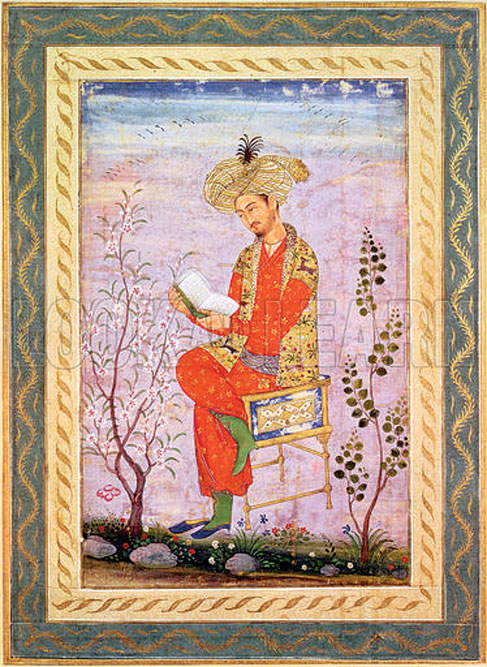

Above all, he loved books. His first act after a conquest was to go to the library of his opponent and raid its shelves. Whenever he visited a new city he would go to poetry meetings and listen to the verses being recited by its poets, joining in where appropriate and criticising whenever he disliked a particular couplet. Bad poets were a particular source of irritation to the connoisseur in Babur. One distant cousin he admired for his table and administration—‘everything of his was orderly and well-arranged’—but castigated him for kidnapping beautiful boys for his bed (‘that vile practice’) and even more so for his ‘flat and insipid verse—not to compose is better than to compose verse such as his’.

His sensibilities sharpened by wide reading, Babur had a great gift for producing these witty and often piquant word-portraits of his contemporaries. His own father he described as ‘short in stature with a round beard and a fleshy face, and was fat. He wore his tunic so tight that to fasten the ties he had to draw in his belly; if he let himself go, it often happened that the ties tore away. He was not choice in dress or food… In his early days he was a great drinker. Later on, he used to have a party once or twice a week. He was good company, talkative and well-spoken man… He was fun to be with in a gathering and good at reciting poetry to his companions’.

The Baburnama is an intriguingly mixed bag of such character sketches blended with musings on a wide variety of subjects: it is at once a diary, a history, a collection of nature notes, a gazetteer, a family chronicle and book of advice of a concerned father to a slightly hopeless son. It is divided into three equal parts. The first tells of his childhood and the adolescent failures that led to the loss of his patrimony. The second tells of his early twenties and his time spent homeless and wandering beyond the Oxus. This is followed by the lucky capture of Kabul, which he then uses as a base to rally his exiled and scattered Timurid relatives. The third tells the story of his final years and the conquest of India, a triumph tainted in its author’s eyes by the ever-present pain of exile and loss. History may remember him as the first Mughal emperor, but in his own eyes he was always a refugee.

Much of the text is a record of Babur’s restless energy and ambition, his struggles in a world that is inevitably profoundly male, military and feudal: fighting, riding, polo, drinking, swimming, fishing and hawking occupy many more pages than more peaceful pursuits such as chess, painting, calligraphy, romance, versifying or lovemaking. But even the most relentlessly masculine passages are redeemed by Babur’s personal modesty and his awareness of his own failures, which he depicts as leading directly to the displacement and the exile of his people. He gives as much space for battles lost as he does to battles won, and he takes full responsibility for his youthful failures: ‘These blunders,’ he writes, ‘were the fruits of inexperience.’

He is also frank about his capacity for grief and depression, and open about the great tragedies of his life and the way that they brought about his darkest moments. He writes with palpable feeling about his mother’s death from fever; his favourite sister’s capture and rape by his Uzbek enemies; and the death of his comrades-in-arms: ‘His death made me strangely sad… ,’ he writes at one point. ‘For few have I felt such grief. I wept unceasingly for a week or ten days.’

He sets out at the beginning that he intends to hide nothing, however badly it may reflect on him, and he remains strikingly true to this undertaking: ‘In this history,’ he writes, ‘I have held firmly to it that the truth should be reached in every matter, and that every act should be recorded precisely as it occurred.’ Partly as a result of this, the Baburnama also records much that is to our eyes unflattering. In this way it provides evidence for those in India, particularly from the Hindutva right, who today look on Babur as a barbarous and bloodthirsty jihadi invader.

For all the examples of his intense sensitivity towards botany, his love of poetry and calligraphy and painting, he also records himself ordering the slaughter of captives, the bloody torture and impaling of rebels and the enslavement of the women and children of his enemies. He even records building pyramids of skulls. These were, after all, extremely violent times. Like Alexander the Great, Rajaraja Chola, a Florentine prince of the age of Machiavelli or an Elizabethan poet-privateer of the age of Sidney or Drake, Babur was a man of ruthless, even pitiless, action as well as one of extraordinary sensitivity. As Stephen Dale puts it, Babur shares with his Renaissance contemporaries ‘the cultivation and refinement of aesthetic sensibility amidst a brutal life of constant political and social violence’.

The parallel with the Italian Renaissance also struck Salman Rushdie: ‘The Western thinker whom Babur most resembles is his contemporary, the Florentine Niccolo Machiavelli,’ he wrote in his brilliant essay on the Baburnama. ‘In both men, a cold appreciation of the necessities of power, of what would today be called realpolitik, is combined with a deeply cultured and literary nature, not to mention the love, often to excess, of wine and women. Of course, Babur was an actual prince, not simply the author of The Prince, and could practice what he preached; while Machiavelli, the natural republican, the survivor of torture, was by far the more troubled spirit of the pair. Yet both of these unwilling exiles were as writers blessed, or perhaps cursed, with a clear-sightedness that looks amoral; as truth often does.’

Babur, in short, was at once the most refined of aesthetes—personally warm and loyal, with a sophisticated and sensitive mind—and also what we today might regard as a war criminal: casually violent and quite capable, when necessary, of overseeing acts of mass murder. As Rushdie concludes, ‘Who then was Babur—scholar or barbarian, nature-loving poet or terror-inspiring warlord? The answer is to be found in the Baburnama, and it’s an uncomfortable one: he was both.’

From the opening page, Babur’s love of nature and the fineness of his descriptive eye are immediately apparent as he evokes his lost homeland, the Farghana Valley. throughout the text, Babur’s eye is alert for natural beauty and inquisitive about its curiosities

Amid so much in his memoir that is deeply human and which speaks to us with so much immediacy, it is this interplay of the sophisticated and warmly familiar with the alarmingly foreign and brutal that, more than anything else, gives the Baburnama its compelling complexity.

THE FARGHANA VALLEY is the Kashmir of Central Asia. The Soviets tried to turn it into an industrial zone, the focus of several Five Year Plans, intending to create a mass regional monoculture of industrialised cotton. But the cotton business died along with the USSR and the region is now quickly reverting to the beautiful, high-altitude Eden it was at the time of Babur.

The valley is reached from the steppe around Tashkent by a winding mountain road which climbs steeply through Alpine meadows. Then, at the top of the pass, you pass through a rain shadow—a high-altitude desert, declining, as you descend, into scrubby, arid steppe grassland. Then quite suddenly, at the bottom, the desert blossoms and beyond the first green fields of rich spring wheat you see the bubbling irrigation runnels, muddy with fresh snowmelt from the Kyrgiz Pamirs, that have brought about the transformation. Beyond these fields, framed by jagged snow peaks, lies the fertile fruit basket of Babur’s beloved Farghana.

As you drive along avenues of poplar, rolling meadows full of poppies and wild tulips flank an expanse of apple, mulberry, apricot and almond orchards, all heavy with ripening fruit. In the distance, on the higher ground at the edge of the valley, are vineyards. Next to some of the larger irrigation runnels—bubbling streams of snowmelt from the Tien Shan—men sit crosslegged on wooden charpoys, in the shade of poplars, eating tent flaps of naan and long skewers of shashlik. Flocks of fat-tailed sheep are grazing amid the meadows. Donkeys rest by the roadside. An old man casts a fishing line from a bridge.

The green intensifies as you progress, until eventually the poplars mass into thickets around the oxbow meanders of the Amu Darya, Alexander’s Oxus. Directly above its banks rise the precipitous mud brick walls of the greatest fortress of Farghana and its ancient capital: Akshi. The sun sets behind the snowpeaks; below, waterfowl call to roost. There is no one about. The town was destroyed and left deserted by a cataclysmic earthquake of 1621, but even in complete ruination, you can sense the massive grandeur and might of this place in its Timurid glory days.

Babur was at once the most refined of aesthetes—personally warm and loyal, with a sophisticated and sensitive mind—and also what we today might regard as a war criminal: casually violent and quite capable, when necessary, of overseeing acts of mass murder

Babur was born here, in Akshi, in 1483. The cataclysmic 13th century conquests of Genghis Khan (most active between 1218 and 1221) followed a century later by those of Timur (1336 to 1405) had between them destroyed the old global order and utterly changed the complexion of the world between the Mediterranean to India; but it left Central Asia one of the richest regions on earth and Akshi as one of its most imposing and impregnable fortresses.

Timur had hauled back to Samarkand the greatest craftsmen, artists and intellectuals from every region he conquered and through their captive labour turned his steppeland capital into one of the great cities of the world. A major cultural renaissance followed, as the Timurids— dubbed ‘the Oriental Medici’ by the aesthete and travel writer Robert Byron—transformed themselves into refined litterateurs, connoisseurs of painting and poetry and calligraphy, as well as scientists, mathematicians and astronomers. This moment of cultural efflorescence was still at its height when Babur was born. In Herat, the centre of this Timurid Renaissance, Babur’s cousin Shah Rukh was ruling over a court of extraordinary talent where the great Bihzad painted his masterworks and Shah Rukh’s sons argued over the superior literary talents of Khusraw or Nizami, comparing poems, ‘line by line’.

Babur was directly descended from both of the great world conquerors: from Genghis and his son Chaghatai (1162-1227) on his mother’s side, and from Timur on that of his father, who was one of Timur’s many grandsons. But the cultural achievements of Babur’s generation were not matched by political or military triumphs. Instead Timur’s many descendants fought among themselves over his inheritance, and each campaigning season brought another round of internecine family feuds: an endlessly repeating cycle of raids and invasions, alliances and betrayals. As EM Forster noted in his essay on Babur, ‘There were simply too many kings about and not enough kingdoms. Tamerlane and Genghis Khan had produced between them so numerous a progeny that a frightful congestion of royalties had resulted along the upper waters of the Jaxartes and the Oxus, and in Afghanistan. One could scarcely travel two miles without being held up by an Emperor.’ Babur put the same thought more succinctly: ‘Ten darwishes can sleep under a single blanket,’ he wrote, quoting a proverb, ‘but two kings cannot find room under one clime.’

The Baburnama opens with a panorama of the final years of Timurid Central Asia, just before the rule of Babur and his cousins was snuffed out for ever. Babur tells how his father died, in a fall from his pigeon house in 1494, when his heir was barely 12 years old. Immediately, two Timurid uncles invaded his lands, while several of his father’s nobles tried to replace him with his more malleable younger brother. Babur saw off both threats and even, briefly, managed to capture Samarkand at the tender age of 14.

But a new and much more formidable enemy soon appeared on the horizon. Taking advantage of Timurid in-fighting, the disciplined cavalry of the Uzbek warlord Muhammad Shaybani Khan (1451-1510) took Samarkand from Babur, easily outmanoeuvring and defeating his inexperienced teenage opponent. Next, Shaybani took Bukhara, then Tashkent. Then, one by one, in a startling short time, he overthrew each of Babur’s feuding cousins and kinsmen, none of whom seemed to realise the seriousness of the Uzbek threat until too late.

‘They went to pieces,’ wrote Babur, ‘and were unable to do anything, Neither could they gather their men nor were they able to array their forces. Instead, each set out on his own.’ Babur claims he tried to raise the alarm: ‘An enemy like Shaybani Khan had arrived on the scene, and he posed a threat to Turk and Mughal alike,’ he wrote. ‘[I argued that Shaybani] should be dealt with now while he had not yet totally defeated the nation or grown too strong, as has been said:

Put out a fire when you can

For when it blazes high it will burn the wood.

Do not allow an enemy to string his bow,

While you can pierce him with an arrow.’

But the Timurids failed to unite, and defeat continued to follow defeat. Babur’s final stand was in his birthplace of Akshi, in June 1503. His outnumbered men, perhaps 400-strong, failed to staunch the relentless Uzbek attack and by evening Babur was leading his last companions through the east gate, fleeing for their lives into the orchards below, as the Uzbeks pursued them on horse. ‘That was no time to make a stand or delay,’ he wrote later. ‘We went off quickly, the enemy unhorsing our men.’ Many were killed and his half-sister, Yadgar Sultan Begum, was captured. By sunset, Babur found himself with only eight men, one of whom offered him his horse. ‘It was a miserable position for me,’ wrote Babur.

‘He remained behind. I was alone.’ Babur hid and was soon discovered, but somehow managed to convince his enemies that he would reward them handsomely if they helped him escape.

He then wandered forlornly from cousin to cousin, looking for opportunities to make a comeback, but without success: ‘I endured much poverty and humiliation,’ he wrote. ‘I had no country or the hope of one. Most of my retainers dispersed, and those left were unable to move around because of destitution… .

It came very hard on me. I could not help crying.’

Worse was to follow in the months that followed as the last of his cousins north of the Oxus were, one by one, defeated, captured or killed. By the age of 22, Babur and his extended family had lost everything: ‘For more nearly 140 years,’ he wrote, ‘[these lands had belonged] to our dynasty.’ Now he and his people were reduced to utter destitution.

Babur wrote this first section with all the elegiac love of an exile for a world he knows he has lost forever and will never see again. As a result, it is also the part of his book that is most challenging to read: charmingly nostalgic in small doses, it is also at times a bewilderingly, even numbingly, detailed record of the lost world of Timurid Central Asia and the annihilated Timurid nobility that once peopled it.

It was as if setting it down minutely on paper could somehow preserve a fragment of what had been lost.

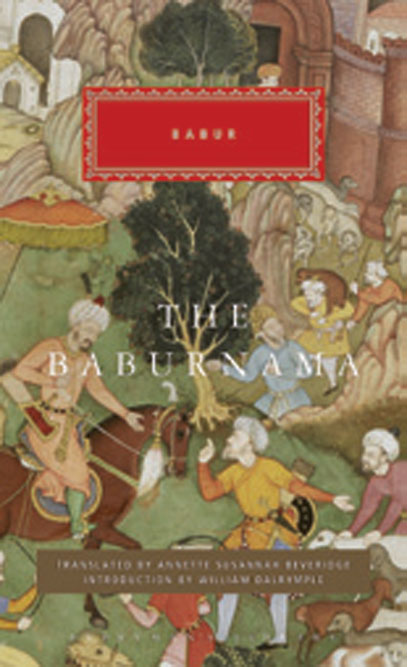

(This is the first part of an edited excerpt from William Dalrymple’s introduction to The Baburnama, translated by Annette Susannah Beveridge (Everyman’s Library; 1,032 pages; $30)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-AfterPahalgam.jpg)

More Columns

The Asia University Ranking 2025 Declared Open Avenues

REVA University Open Avenues

ICFAI: Nurturing Excellence through Innovation Open Avenues