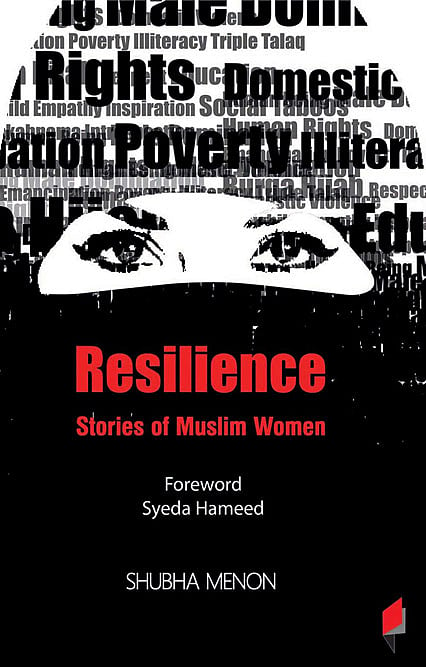

Armed with Diplomas

In Resilience: Stories of Muslim Women, author Shubha Menon follows the lives of the students of a unique educational initiative conducted by social activist and literacy advocate, Shabnam Hashmi in the early eighties. In the book, we read the stories of 11 young women who studied at the Seher Adult Education Centre in Nizamuddin Basti, a place which, the author says, cannot be located on any map of Delhi.

Nizamuddin Basti comprises of a constellation of buildings built around the dargah of the Sufi saint, Nizamuddin Auliya. Its existence dates back centuries and it has over the years earned the reputation of being a place of refuge for people seeking escape from misfortunes and dislocation. Though crowded and congested today, the basti hangs on to its illustrious history, with shops and homes sharing space with the graves of illustrious rulers and common people.

During a break from college, Hashmi started teaching at a literacy centre operating in the basti but discontinued after sometime due to various reasons. Later when Syeda, one of her students approached and requested her to continue teaching, Shabnam Hashmi started the Seher Adult Education Centre in a small room offered by a well-wisher living in the basti.

Syeda, a mother of two, who was married and widowed at a young age, had realised that she needed an education to get a job so that she could feed her children without putting additional burden on her father, a maulvi with limited means. Syeda and her sister, Farida, were among the first students of the centre which had to fight conservative mindsets to keep functioning amidst continuous hostility. The educational initiative and the people associated with it had to bear the anger of the residents who felt that educating young girls and women would lead them astray. Menon’s narrative puts this fear to rest by showing how the young women, armed with diplomas and degrees managed to break free from the shackles of patriarchy and rigid customs and got jobs ranging from social workers to teachers to political party workers.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

We see that the force behind the initiative, besides Hashmi’s efforts, is the determination of the mothers of the people involved in the unique educational experiment, including Hashmi’s mother. Referred to as Ammaji by the Seher educated women, Qamar Azad Hashmi, supported her daughter by taking classes in various subjects and also by raising the awareness of the young women about their rights and the world beyond the basti.

The author brings alive the atmosphere of the basti as she leads the readers through its narrow lanes bringing images of houses and shops leaning into each other amidst the aroma of seekh kababs and notes of Urdu and Arabic floating in the air. The narrative is further enlivened by anecdotes about the many graves scattered in the basti—ghosts that share homes with residents and sounds of galloping horses speeding away at night.

The book also touches upon the contradicting presence of the Tablighi Jamaat, dedicated to orthodox Islam, in this locality that owes its existence to the dargah of a Sufi saint, each existing parallel to each other without any major problems. Menon had also included the views of lawyers and activists in an effort to understand the provisions of Muslim Personal Law, a current favourite topic of debate.

The book could have benefited from a good editorial hand, particularly the structure of the book, which creates confusion at times. The narrative thoroughly engages while recounting the stories of the young women who moved past the shackles of conservatism and created successful lives for themselves and their children. Though there is a sincere attempt to understand Muslim Personal Law and associated legal pronouncements, the topic is too vast to be contained in a few pages and hence seems one directional. Menon does an effective job of breaking the stereotypical image of Muslim women, showing how literacy can improve lives and help fight injustice.