America First

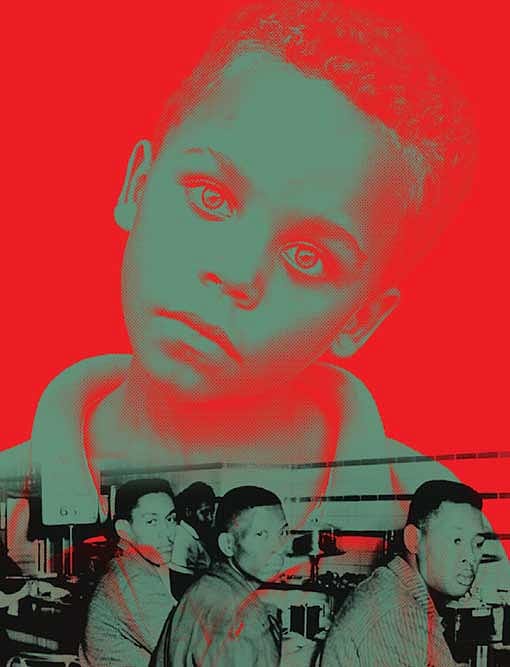

IN THE NATIONAL Book Award- winning Sing, Unburied, Sing, Jesmyn Ward juxtaposes the America of today, where any Black boy can die from police brutality at any time, with the Jim Crow era, which still lingers in the memory of the aged. Among this generation are Mama and Pop, as Philomène, a magnificent traditional healer dying of cancer, and her husband, a gentle man actually named River, are known to their grandson Jojo.

The novel unfolds in three voices, opening with Jojo trying, painfully, to assist his grandfather in slaughtering a goat. It is his 13th birthday, and his mother will soon neglectfully buy him a baby shower cake, another reminder of how fortunate he is to live with his grandparents. At times, Jojo's narrative can seem too sophisticated, especially as compared to his speaking voice. This settles once the reader recalls that Jojo is gifted with extrasensory perception: he can hear what cannot be expressed, the thoughts of animals and of his toddler sister, Kayla, whose vocabulary has been slow to develop. It's a credit to the seamless way in which the supernatural and the mysterious are spoken of in this book that we sometimes forget this detail. Later, we learn that like others in his family, Jojo can also see and communicate with spirits.

Jojo's mother Leonie, who had him as a teenager, is the second voice. She takes her children along for a long drive to the prison from which their father, Michael, is about to be released. Michael is a White man whose cousin killed Leonie's beloved brother, Given, whom she still sees when high on meth. Much of the book's action takes place on this journey, where the children are exposed to everything from thirst and nausea to a police encounter. The third voice enters the book later: Richie, a ghost of Jojo's age, joins the family on the car journey back from Parchman, where Michael was serving time and where a horrifying incident from Pop's own youth took place.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

It's difficult to think of this family as a broken one—despite the drugs, incarceration and disease—because the love in this book goes at least as deep as the decay. When Ward writes of love, every character is redeemed. Most profound among these loves is what exists between Jojo and his grandparents. It shimmers in countless quotidian acts, just as his vigilant care for his sister does. The love between Mama and Pop, too, is full of tenderness—palpable even while she ails, out of sight of the action. Then there's the exhilarating selfishness of the romance between Leonie and Michael, a love that almost has room for no one else, not even the children it has brought into being, although Leonie's own love for her mother is almost luminescent— "I thought about that Medusa I'd seen in an old movie when I was younger, monstrous and green-scaled, and I thought: That's not it at all. She was as beautiful as Mama. That's how she froze those men, with the shock of seeing something so perfect and fierce in the world." Even one of the ghosts aches with love, plaintive with longing for the only man he knows as his father. Yet, again and again we are also shown how there is no real redemption.

This is a book that gets better with every page, so that by the time we are halfway through, all the earlier confusions—from the unevenness of language between Jojo's articulations and observations to various small points lost in the non-linear, occasionally dense, lyrical style— fade. As its climactic pages and the inevitable death they contain draw nearer, Sing, Unburied, Sing demands stepping away to recalibrate before returning. Devastation is unavoidable, both in and by this impressive novel. Ward saves her choicest moral ambiguities for near the end, so we find ourselves in medias res even then—haunted, as are all her characters.