Amartya Sen: A Prologue to Greatness

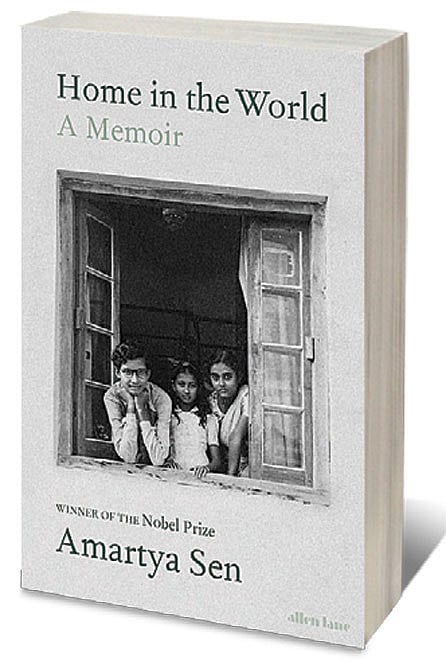

What would one expect of the autobiography of a formidable world-renowned intellectual, bedecked a quarter century ago with a Nobel Prize for Economics and a Bharat Ratna? Four hundred pages of technical jargon and algebraical formulae? Or a charming, immensely readable, and very enjoyable voyage through the making of a great mind—and a very good human being? Actually, Home in the World (Allen Lane; 480 pages; ₹899) is only a memoir of the first 30 years or so of Amartya Sen’s life story. He has spun it out over ten years of intermittently working on it, and in the process, almost given up on his earlier project of recounting the whole of his 88 years in five volumes. That is a loss for humanity but we should be grateful that we have this fragment that explains how a boy who stood 33rd out of 37 in his school at St. Gregory’s, Dacca (as it was then spelt) went on to become Master of Trinity College, Cambridge; President of the Indian and American Economic Associations; and President also of the International Econometricians Association—but we are not vouchsafed these achievements beyond a bare mention of them. Instead, we are just led with rare good humour and gentle wit through the formative years of his life—possibly the most significant three decades of his life. The rest of can be read up in Wikipedia.

Let me illustrate with two delightful vignettes. The first is from his first day at Cambridge. He is directed by the Porter’s Lodge to his lodgings (‘digs’). He is received warmly enough by the landlady, but when he suggests having a bath, her brow clouds over. She anxiously enquires whether his colour won’t wash off when he slips into her snow-white tub, and is immensely relieved when 20-year-old Amartya assures her it won’t (and goes on to become such a strong advocate of racial equality that when she finds no one partnering an African at a dance, she offers to dance with him, and dances for two hours till he begs off with fatigue!).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The other vignette which I must share at the outset of this review, to give you a flavour of what you might expect, is from a hitch-hiking trip in Scandinavia that he and Rehman Sobhan (later, among Mujib’s principal lieutenants in the great fight for Bangladesh) undertook together. Norway goes fine but lifts in cars dry up soon after they enter Sweden. A car that swooshes past them, then suddenly reverses. The driver explains that his child in the rear seat wants to take a good, long look at Rehman’s beard. The hitchhikers are then kindly taken in hand and over dinner asked about the dietary preferences of Hindus and Muslims. Sen explains how Hindus regard the cow as holy and, therefore, don’t eat beef, while Rehman patiently tells their host that Muslims don’t eat pork because pigs are dirty. As they take their leave, the kindly, if slightly dazed host, expresses his hope that they will meet again as he is puzzled as to why the pig is regarded as holy!

Anecdotes like these sparkle in every chapter and almost every section ends with an epigram or reflective line that reverberates for long in the reader’s mind. This is a very accessible book, “fun” to use one of Sen’s favourite words, written in beautifully constructed short sentences that explain the most profound observations with commendable brevity. Astonishing when one learns that Sen regards English as his “third language” after Bengali and Sanskrit. One is brought up with a start when he tells a friend that he “dreams in Bengali”. For his command of English is exquisite. The famous English-language novelist, Joseph Conrad, who was born and grew up in Poland and only learned English when England hove into view in his twenties, comes to mind—although the comparison ends there. It is Sen’s capacity to maintain a simple style while telling amusing stories or explaining complex issues (as he does occasionally) that is both unique and captivating. “Good language,” he remarks, “is a product of discerning love”.

As is the amazing range of his interests. Far from being a dull don obsessed with his academic preoccupations, Sen loves a good meal in congenial company, has a discriminating nose for the best wines, takes note of beautiful women, adores world-class paintings and sculpture and heritage buildings, attends architectural digs with deep curiosity, and is bewitched by outstanding plays, poetry, music, the enchantments of Nature, and, above all, interacting with his peers, with many of whom he disagrees, in the give and take of rational argument—a whole human being, a bon vivant with a brain unmatched in his field and a heart that is all too aware of the wretched lot of most of humankind.

He is also an extrovert, revels in argument, takes on giants with whom he is as ready to listen as speak his mind, and as uninhibited in agreeing with them as in expressing dissent—a living monument to his later exposition of The Argumentative Indian (2005). Eclectic in his friendships, he counts among them not only a host of Oxbridge Indians and Pakistanis from both wings but also a brace of Sri Lankans; a Filipino; a Japanese; a Norwegian; a Thai; an Israeli; a South African, and a Sudanese who had been brought up in Egypt, most of whom went on to high distinction in their respective countries; and, yes, two Brits, Michael Nicholson, with whom he formed his “closest friendship as a student” and Claire Royce (although one is left wondering whether he was more taken with her or her mother), plus any number of Italians, besides the cream of philosophers and economists of his time, and up to a generation or even two older than him, that he finds among the British academics and East European refugees like Nicholas Kaldor and Frank Hahn. He finds escape from the rigidities of the Cambridge stand-off between the “neo-classicists” and those who called themselves the “neo-Keynesians” in the far more congenial and open-minded atmosphere of the daily Faculty lunch at Harvard. His exposition of Karl Marx is the most outstanding and comprehensive that the general reader of any discipline could access elsewhere. His affection for the economist Joan Robinson remains undiminished by his strong disagreements with her. His principal guide as an undergraduate is his Director of Studies, the eccentric but brilliant Piero Sraffa, a close associate of Antonio Gramsci, the Italian communist who paid with incarceration for his relentless criticism of Mussolini and fascism.

Sen’s own desire to widen the scope of economics from “marginal this and marginal that” to something with wider application to rectifying incorrigible injustice and endless deprivation is what makes him and his work—more than his technical expertise in mathematical economics—into a concerned human being for whom societal welfare includes liberty and freedom among the fundamental axioms of welfare theories that otherwise only deal with maximising output, or surplus or profits, and stretch to wondering how to reconcile collective choice with individual freedom to choose. His most influential mentor was Maurice Dobb, an unrelenting life member of the British Communist party, who was admitted to the Trinity faculty only on pledging two weeks’ notice to the college of any intention to bomb the chapel!

The pages overflow with a galaxy of the greatest minds in economics and philosophy—but artlessly, for Sen is at ease meeting and endlessly arguing with them, taking the reader into confidence about the key thoughts and contradictions of the best and the brightest across the spectrum of ideology, by-lanes into which I (and almost everyone I knew as a student) would not have dared venture. With Sen to guide you, you can either watch with fascination or join in the argument, if you feel like it. What is important is that nothing useful emerges till there is a dialectical clash of opinion, and creative reasoning is the lubricant for rational outcomes.

Looming over the book is the influence of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, his most important lieutenant, Kshiti Mohan Sen (Amartya’s grandfather), and Santiniketan. Their humanism, their global vision, their insistence on breaking the walls of “narrow nationalism”, and their principled dedication to secularism, harmony and the celebration of diversity constitute a kind of leitmotif of Sen’s life. He emerges from Santiniketan as deeply immersed in Sanskrit classics as in mathematics and physics, steeped in a sceptical study of Hinduism’s most sacred texts, a Buddhist in all but name in consequence of frequent school visits to nearby Nalanda and much assiduous study of Buddhist writings, and an ardent votary of what we have come to call the “composite civilisation” of India. This is reinforced by intense discussions with friends in the Coffee House on College Street outside Presidency College in Calcutta and then the even wider horizons of both Cambridge, UK and Cambridge, USA, besides the Delhi School of Economics in its heyday.

The one missing element in this autobiography is his emotional life. He has kept to himself the lead up to the three most important women in his life: his first wife, a Bengali poet of note and a scholar of comparative literature, Nabaneeta Dev (whom I knew well as an undergraduate and later); Eva Colorni, his second wife; and Emma Rothschild to whom this memoir is dedicated. I am not complaining that this is not a ‘kiss and tell’ memoir since privacy is his right. This memoir is, instead, an unforgettable story of the evolution of a thinking and enquiring and all too human a mind, as also a tribute to one who has harnessed his abundant academic talent to the needs of the humblest and poorest: a truly great human being whom I have had the privilege of being acquainted with since his first lecture as a duly appointed Lecturer at Cambridge in Michaelmas term 1961, and a gracious host in his flat at 15, Trinity Street in the immediate vicinity of my college, Trinity Hall.

Mandalay, Dhaka, Santiniketan

For the future author of Home in the World, Sen’s life begins appropriately in ‘Jagat Kutir’ (Global Cottage), his family home in the old city of Dhaka, but moves soon enough to Mandalay where his father is appointed to the University faculty. “The importance of women” is “a strong memory…from my childhood recollections of Burma” and has “influenced my attitude to gender-related issues…which would later become one of the subjects of my research”. But “the Burmese whose kindness impressed me so much as a young boy” have turned brutally hostile to the Muslim Rohingya, and “trained to become violent haters.” This includes Aung San Suu Kyi, “a remarkable and brave person who tolerated awful harassment and prolonged incarceration to fight for democracy”; only, once she succeeded, “something went terribly wrong…reflected particularly in her unwillingness to help the Rohingyas … and other minority groups…who have had to endure barbarities, torture and murder in an organized pogrom…There is a lesson here which is peculiarly important today in formerly secular India”: “formerly” says it all.

He is brought back to Dhaka and put into St. Gregory’s, which he finds “stifling”. He stood 33rd in a class of 37. Wanly, he remarks that he became a good student “only when no one cared whether I was a good student or not”. That transformation the world owes primarily to the bombing of Calcutta and other Bengal targets by the Japanese. It was that which convinced his parents to send him to Santiniketan to be nurtured in the relative safety of rural Bengal by his maternal grandfather, Kshiti Mohan Sen, second only to Gurudev in the Santiniketan hierarchy, who prised open young Amartya’s mind and revealed to it the limitless possibilities of learning. “I really enjoyed exploring Santiniketan’s open-shelved and welcoming library…and I absolutely loved not having to perform well.”

He was also much taken with the “freedom in deciding what to do”, asking “questions unrelated to the curriculum”, “little enforced discipline” and “a complete absence of harsh punishment”, as also, of course, chatting with his “intellectually curious classmates”, including the girls who “were a lot more intelligent and talented than they liked others to think”. He attributes this to a “psychology of modesty” that societal mores were imposing on them. Above all, it is “the capacity to reason” and “fostering curiosity rather than competitive excellence” which Santiniketan cultivates that he cherished, along with the “novelty of outdoing” his mathematics teacher, the formidable Jagabandhuda, with reasoning “something of my own”, typified by his remarkable retort for a teenager, “I think I can work out where a projectile might land, but I cannot get excited about this calculation”!

The cosmopolitanism of the ethos, “an Indian school with a commitment to pursue the best of the knowledge in the world”—with Arabic and Persian and Japanese and Chinese scholars in residence, but also “class discussions that could move from traditional Indian literature to contemporary as well as classical Western thought, and then to China or Japan or Africa or Latin America “made a great impression on young Amartya’s mind, reinforced through visits to Santiniketan by intellectuals from all over the world: Eleanor Roosevelt—“a model of humanity and clear-headedness in a very murky world”; Sylvain Levi; William Pearson; Leonard Elmhirst; Mahatma Gandhi’s great friend, Charlie Andrews; Gandhi himself—who says impishly of Rabindra Sangeet, “The music of life is in danger of being lost in the music of the voice”—Chiang Kai-shek and his “stunningly good-looking” wife; and one Indian who towers over everyone else, the renowned Bengali poet and “family friend”, Syed Mujtaba Ali. His “closest” and “life-long” friend is Tan Lee, son of the Professor of Chinese studies at Santiniketan, Tan Yun-Shan. Thus were the windows opened to Amartya learning to be Home in the World.

As for sport, the “peak of athletic gory” for Sen was winning on India’s Independence Day the championship of the ‘sack race’ by working out that it is “hopeless” to jump forward but “you can with stability shuffle forward with your toes in the two corners of the sack”. He was a complete flop at football and hockey with “pass-grade skill in badminton”, but his record in cricket, as a tolerable batsman but not at bowling or fielding, “was close to adequate”. Where he shone was at starting and running a school for tribal children, editing short-lived school magazines, and public speaking, learning to “live with the loud scorn of those who disagreed with me”. This “vastly expanded one’s ability to take adverse criticism”.

Thanks principally to his grandfather, Kshiti Mohan Sen, a giant scholar of Hinduism and arguably the greatest influence on Amartya’s intellectual development, who took Amartya’s atheism in his stride, directing his attention to “the atheistic Lokayata—part of the Hindu spectrum” and Madhavacharya’s Sarvadarsana Samgraha (Encyclopaedia of Philosophies), where Amartya discovers in the first chapter a “defence of atheism and materialism” that is “one of the best expositions of those perspectives”, as well as the godless Charvakas, who have an equally revered place in Hindu philosophy. And, of course, the ‘Song of Creation’ in Mandala X of the Rig Veda that begins by describing the miracles of Nature, then asks who created all this before replying, “Only He knows”—and then comes the punch line, “And perhaps even He knows not”. (There are numerous English translations of this famous verse, so I am paraphrasing rather than translating).

As an eminent authority on Hinduism, grandfather Kshiti Mohan was so impressed with the Muslim Sufis that he learned Persian and became an expert on “the pluralistic religious tradition of (Sant) Kabir” and later the Bauls who lived in the vicinity of Santiniketan, “who had a similarly capacious outlook”. It was “with the strong encouragement of Rabindranath that Kshiti Mohan started publishing collections and commentaries on Kabir, Dadu and other visionary rural poets”. Sen’s name appeared in print in the acknowledgements section of KM Sen’s Hinduism, second only in renown to Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’s The Hindu Way of Life.

Most lasting perhaps of Santiniketan’s impact on Amartya Sen’s thinking was its intensely spiritual atmosphere infused with a sincere respect for all religions, “against the intellectual priorities given to separatist histories of Hindus and Muslims… (and given how) extensive and creative interactions between Hindus and Muslims have actually been, especially among the common people”. Says Sen, “The constructive mutual influences between Hindu and Muslim traditions in India was relevant enough when the book was written, but it has become immensely more important over the decades, thanks to the championing of aggressive and insular interpretations of Hinduism in contemporary South Asian politics”. Too true.

There were three other major issues that marked Amartya’s growing up years in Santiniketan: the differences between Gandhiji and Gurudev Tagore despite the huge respect and admiration they had for each other; the Bengal famine of 1943; and the Partition of Bengal in 1947 when Amartya was 14.

Gandhiji advocated 30 minutes of spinning the charka every day as the “foundation of an alternative economics”. Tagore preferred the “liberating role of modern technology in reducing human drudgery (and) poverty”. Sen does not mention it but here clearly lies the core of his doctoral thesis (which he wrote in a year, whereas Cambridge rules stipulate that the Ph.D. candidate must cogitate over at least three). The Choice of Techniques, as the published version was titled, made Dr. Sen’s international reputation as the new kid on the block. (I have always wondered why he used so obsolete a word as “techniques” when “technology” was already much in fashion).

The Bengal famine came to Amartya’s doorstep, as it were, just as he was turning ten. Beginning with the cruel bullying he witnessed of a young, emaciated boy, driven out of his mind by hunger (who had not eaten for a month), over a lakh of famine-stricken destitute persons passed through Santiniketan en route to Calcutta—“a torrent of miserable humanity”. They had been told that in the city some charities were providing something in the guise of famine relief. It was the start of one of his major contributions to an understanding of why famines occur and how they can be stopped: as “there is a huge difference between food availability (how much food there is in the market as a whole) and food entitlement (how much food each family can buy in the market)”, the policy focus should be on “food entitlement—not food availability”. And the crux of ensuring such policy focus is “information”. The more information available in the public realm about the horrors of food shortage, the quicker will governments step in. That, in turn, means that democracy and its handmaiden—a free press—is the most important prophylactic against death by starvation.

The partition of Bengal brought Amartya Sen much heartache and led to one of his most influential works, Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (2006). The emotional trauma, from which the path-breaking book sprang, began in 1944, when, in midst of “the beastly horror and terrible consequences of engineered divisions and cultivated hostility”, one of their day-labourers, a Muslim called Kader Mia, staggered into the garden of their Dacca home bleeding, having been “severely knifed in his back as well as his front”. Sen “found it impossible to understand—or even fathom at all—why Kader should have been killed by assassins who did not even know him”. Sen’s later studies showed irrefutably that “most of the people killed in the Hindu-Muslim riots of the 1940s shared a class identity”. The only area where they differed was “in their religious or communal identity”. Was then this degraded bestiality the consequence of what his grandfather, Kshiti Mohan Sen, believed was their “comprehensive ignorance of the history of India” or the consequence, as Joya Chatterji has argued, of “the privileged parts of the Hindu middle and upper classes (who highly valued education from primary to graduate and post-graduate levels—MSA) worked for the partition of Bengal” (emphasis in the original) because they feared they “would lose their power and prominence” if the Muslims, who were in a clear majority, were to democratically come to office in an independent democracy”.

Sen, drawing heavily on his grandfather’s acute historical analysis, points out that, apart from the generally secular ethos of Mughal rule which associated Hindus in large measure with governance in the maintenance of law and order, administration in general and revenue collection in particular, and high military positions besides constituting the bulk of the Mughal armed forces, “Bengali Muslim rulers did not seem to want to displace the comfortable position of the Hindu upper and middle classes, nor to force them to embrace Islam”. Conversions were largely confined to “the outer reaches of Hindu society” who were, in any case, “barely integrated into Hindu society itself”. But, under Cornwallis’ notorious Permanent Settlement of 1793, “most” of the “severely exploited” tenants were Muslim while “many of the secure landowners were Hindus”. It was thus “essentially” the “issues of land reform and the removal of inequalities and exploitation in land ownership” that led to AK Fazlul Huq, the Bengal leader of the Peasants and Workers Party (please note the absence of any religious denomination in the name of his party) falling for Jinnah’s mischievous ruse in asking Haque to move the infamous Lahore resolution of 23 March 1940 that hinted at partition on communal lines as the destiny of post-colonial India. Indeed, the Sen family were “sympathetic” to Haque’s “basic commitments”. (On a personal note, I am ecstatic that at p.417, Amartya Sen draws attention to my daughter, Sana’s prize-winning undergraduate essay on Fazlul Huq, Region and Religion—published in “Modern Asian Studies”, 42 (6), 2008—that leapfrogged her from Cambridge to a full scholarship at Harvard and on to tenure as a historian teaching South Asian history at MIT). “A person’s religious identity need not annihilate every other affiliation” is Sen’s observation that needs to be indelibly inscribed in the heart of every South Asian, and certainly every Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi—and Sri Lankan in that “island of blood”.

As for the Partition of Pakistan a quarter century after the Partition of India, Sen attributes the emergence of Bangladesh to “language (as) an amazingly powerful influence on the identity of Bengalis as a group on both sides of the political boundary between Bangladesh and India”. (The sceptical Brit or American might be asked why the UK and the US since 1776 remain “divided by a common language”?) Tagore is the common author of the national anthems of India and Bangladesh (and Sri Lanka, although Sen misses this). Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam are the revered poets of both nations. More earthily, Sen cites a venerable Maulvi friend of the family remarking, “My friend, there is no difference between us. You live by exploiting the vulnerabilities of ignorant Hindus, and I live by exploiting the vulnerabilities of ignorant Muslims. We are engaged in exactly the same business.”

Sen concludes, “The history of Bengal is thus a tale of integration, rather than one of religious partition and cultural disintegration. It is that philosophy, that understanding, which makes a united and secular Bangladesh a feasible and elevating idea”. A fit thought on the Golden Jubilee this year of the Liberation of Bangladesh.

The British packed up and scuttled their Empire in India in 1947—and damn the consequences. There is an amusing post-script to this dating from 1973 when Sen was invited by the University of Warwick to deliver the Radcliffe lectures in the name of the same Sir (later Lord) Cyril Radcliffe, the man who drew the partition lines without ever earlier or ever since visiting India or meeting Indians in England. His Lordship relents and agrees to have Sen to tea; then abruptly and at the last moment withdraws his invitation. Sen’s host, the first Vice Chancellor of Warwick, John Butterworth, known universally as “Jolly Jack”, drives the last nail into the coffin of colonialism, remarking, “I always wonder how this lot actually managed to run an Empire”!

There follows Sen’s wise, enlightening and balanced assessment of British colonial rule asking the “methodological question” (note: not “hypothetical” question) posed at Santiniketan: “What India would have been like in the 1940s had British rule not occurred?” “Would India have moved, like Japan, towards modernization in an increasingly globalizing world, or would it have remained resistant to change, like Afghanistan, or would it have hastened slowly, like Thailand?” It is, I think, intellectually significant that the question was not posed in the usual binary manner: was the Empire good or bad for India? (As was, perhaps unfairly said of our history teachers at St. Stephen’s: optimal answer—two “good” reasons and three “bad” reasons, garnished with five quotations”!)

Amartya’s Sen sensitive answer is to refer to the Cambridge historian, Christopher Bayly, saying Ram Mohun Roy “made in two decades the astonishing leap from the intellectual status of a late Mughal state intellectual to that of the first Indian liberal”. From this launch pad, Sen refers to the growing influence on others, like Ishwar Chandra Vaidya and Michael Madhusudan Dutta and several generations of the Tagores, of the “English writings circulating in Calcutta under the East India Company’s patronage” but also points to the example of Japan going “straight to learning from the West without being subjected to Imperialism.” For once, I beg to differ. The Japanese learned a great deal about engineering and business management from the West but nothing about democracy and human rights till American imperialism forcibly imposed on them these basic values of modern governance. Of course, that is what accounts for Japanese barbarism from Manchuria to Nanjing in the Thirties and the countries they cruelly occupied during the second World War.

While Sen approvingly quotes Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore from his famed last lecture on “The Crisis in Civilization” (1941) as centred on “the large-hearted liberalism of nineteenth century English politics” but regretting that what “was truly best in their own civilization, upholding the dignity of human relationships, has no place in the British administration of this country”. And that, says Sen, accounts for the apparent paradox that the “fruits of learning from Britain’s own experience” could be used freely in India “only after the period of Empire had ended”. What a brilliant insight instead of totting up “railways, the joint stock companies and cricket” of the Brits against the reversing in two hundred years of India’s and Britain’s share of global GDP or with “the financial bleeding that accrued to British company officials” which Adam Smith believed had rendered John Company “altogether unfit to govern its territorial possessions” in India.

Yes, India, as Marx maintained, and Sen reminds us, did need a “shock”, but it need not have come in quite the manner the Empire bestowed it, for “it was easy to see how far short the achievements were compared with the rhetoric of accomplishment”. He cites Kipling but I am intrigued that Sen does not mention Thomas Babington Macaulay, who was withering about the decadence of our millennial civilization when the Mughals virtually collapsed into the lap of the Company, but did predict, with eerie accuracy, that the British would not last in India for much more than a century and, therefore, their charge would have to be educated into civilised (i.e. Westernised) self-rule within that time-frame. This is what happened—and the White Man’s burden became the Brown Sahib’s responsibility.

Calcutta and Cambridge

Amartya Sen shifted from Santiniketan to Calcutta (as it was then spelt in English) in July 1951 and almost immediately self-diagnosed carcinoma in his mouth although the many doctors he consulted, including one Dr. Subodh Mitra “who knew about cancer in a general way” but was in fact a leading gynaecologist “who had done innovative work in vaginal surgery (not quite my need)”! No one was ready to confirm 18-year-old Sen’s diagnosis of the lump on his palate without a biopsy and Sen knew that a biopsy itself might lead to the spread of the dreadful disease. The biopsy he was eventually subjected to revealed that he did indeed have Grade II squamous cell carcinoma, with a 15% expectation of survival for five years. While the newly established Chittaranjan Cancer Hospital in Calcutta did not have a specialist surgeon in oral cancer, it did have a resident radiologist who prescribed a “heavy dose of radiation” without surgery. “The hospital had just acquired a radium mould” and young Amartya “spent a lot of time” getting a “lead mould constructed with a recessed chamber for the radioactive material to be placed in it”. The radiation was “a gruelling experience”, not because of any pain but because it was “boring … to sit stationary for five hours each day” until he got Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and Eric Hobsbawm’s “early writings” to read to pass away the dull hours. The horrors of his condition struck later when there was a “veritable inferno in my mouth” and he “painfully sipped the liquid food my mother made for me”. It took “a terrible two months” for the inferno to die out. It did. But Sen was determined to not let “agency” over his health ever slip out of his own hands and thus saved his life when he insisted on expert surgical advice at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge before any surgeon fiddled with his mouth. He not only lived to the great age he has now attained because he kept “agency” in his own hands but also because of his undying admiration for the UK’s National Health Service that made excellent health services available virtually free to all who needed it, bar none.

Cancer and its treatment, however, were not allowed to stand in the way of the joys of the bookstalls on College Street and conversations with friends in the justly celebrated Indian Coffee House. Indeed, it is striking how regular classes and tutorials at Presidency College seem marginal in his remembrances compared to the impact of discussions over “Marx-obsessed” coffee with his student peers. Like most of his friends, he was very much on the left. Sen particularly enjoyed finding merit in Marx’s “labour theory of value” (“which appeared to many to be naïve and simplistic”) because, principally through reading Maurice Dobb’s 1937 classic, Political Economy and Capitalism, Sen learned early the importance of distinguishing “theories of labour value from a theory of price determination”. “Dobb,” says Sen, “argued that the labour theory of value” brings into focus Marx’s emphasis on labour as the key factor of production and was in fact “a factual description of a socio—economic relationship” which, says Sen, “reflects a particular—and important—perspective in which to see the relationship between different social agents—workers, capitalists and so on”. Moreover, in his scathing Critique of the Gotha Programme of Germany’s nascent Social Democratic Party, Marx ends by denouncing the SDP for seeing human beings “only as workers, and nothing more is seen in them, everything else being ignored”. From that is, as Sen found, a short leap to the exhortation in the Communist Manifesto that Marx wrote in 1848 with its resounding call for “Workers of the World Unite”. Sen sees in that call that Marx ensured that “there is no obliteration of the fact that every worker is also a human being.” This, in Sen’s view, “clearly has a much greater relevance for the identity-based conflicts that so dominate the battles in our times”. And “this explains”, observes Sen, Marx’s “highly original concept of ‘objective illusions’ and ‘false consciousness’” that led seamlessly to Marx’s perception of the “workers’ lack of bargaining strength” and why they “do not receive the value of what they produce because of the way markets work” and “the huge inequalities in the ownership of the means of production”.

It was also Sen’s creative and reflective reading of Marx in Calcutta, followed by the clarifications that came from the teachings of Maurice Dobb and Eric Hobsbawm in Cambridge, that led him to understanding Marx’s concept of “objective illusion” as the underlying reason for the “deceptive failure of the workers in an unequal society to see clearly the nature of their exploitation”. Perhaps most significantly, it was Marx’s wide and deep exposition of the human condition that took Sen beyond the technicalities of mathematical economics to the much more human economics of welfare through social choice theory and his life-long interest in studying in this light the causes and solution for “class and gender inequalities” and the imperative of “equity-enhancing politics”.

Tragically, Marx’s advocacy of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” also suffered from “objective illusions” (although Sen does not say so) but Sen does see that it eventually resulted in the awfulness, despite its achievements, of Lenin and Stalin’s brutal modes of governance and the loss of 30 years of opportunity opened by Mao’s revolution but closed by ideological obtuseness until Deng took over. Hence, Sen’s understanding that for “the reach and force of Marxian analyses in quite different contexts from Marx’s own, we need to apply a suitable versatility”. Most orthodox Marxists would repudiate that interpretation—and, therefore, remain stuck in obsolescence.

Sen particularly liked Khrushchev’s story told by him. He asked a child: who had written War and Peace? The terrified boy replied, “Believe me Comrade Khrushchev, I did no such thing.” Khrushchev complained to the head of the secret service that such “public fear and bullying” was unacceptable. After a few days, the secret service assured Khrushchev, “You need not worry any more, Comrade Khrushchev, the boy has now confessed that he did write War and Peace!”

Sen at Cambridge also discovered from Marx’s miscellaneous writings, including The German Ideology (1846), that Marx could not be accused of being indifferent to liberty or the freedom of choice. In fact, he defended individual freedom of choice and “had a powerful understanding of the importance of liberty of choice—and its necessity for the richness of the lives that people lead”.

While my Cambridge meant principally the fairly unsuccessful chase after au pair language students at the International Centre and the rather more successful chase after politics at the Cambridge Union Society, Sen’s Cambridge was a stellar encounter with a host of brilliant brains from all corners of the globe. They included economists of all schools—the Italian associate of Gramsci, Piero Sraffa, as his Director of Studies; Maurice Dobb, the lifelong Communist, as his principal mentor; Aubrey Silberston (who was also one of my supervisors) for the British economy; Dennis Robertson, whose intimacy with Keynes was such that they hardly knew which idea originally came from whom; the dignified Prof. James Meade (another of my supervisors); Nicholas Kaldor, who “regarded the battle between the distinct schools with transparent irony and humour”; Ken Berrill at St. Catherine’s (whose lecture refuting Marx’s interpretation of the laying of the Indian railways disturbed me enough to question Dobb about it but gaining little satisfaction from his answers); a deep personal friendship with his great admirer, the sharp-tongued, if essentially kindly, Frank Hahn (who was my overawing Director of Studies); and so many others it would double the length of this overlong review to mention all of them. An extraordinary number of them were Italian, some of whom were deeply committed leftists and most of them utterly brilliant, original thinkers: Pierangelo Garegnani; Luigi Pasinetti; Nino Andreatta, and Luigi Spaventa, among others. All of them were products of the post-War Italian “economic miracle” that then preoccupied most European intellectuals, including my Director of Studies, as holding exciting prospects for what was then known as the “underdeveloped” world. I must mention Joan Robinson, of the path-breaking Economics of Imperfect Competition (and Edwin Chamberlin’s work on monopolies) that brought classical economic theory crashing from its ivory tower on to ground reality, and Richard Kahn, the unfazed conservative and “follower” of Keynes who gave generous dinners for Sen and Joan to fight out their battles over Ms. Robinson’s decidedly queer views on equitable distribution having to follow, and not be part of the process of accelerating economic growth. She insisted on priority to growing the fruit before eating it and thus disapproved of Sri Lanka’s model which, despite incessant internecine bloodletting, has so raised the island’s human development achievements in education, health, nutrition and the general availability of other public goods as to put the island many leagues above her larger neighbours. Something of a similar order is now happening in Bangladesh and Bhutan. “An academic bond did not form between us,” is Sen’s bald assertion of his relationship with Joan Robinson, who, with her fondness for most things Indian, would have loved to have this bright young Indian student for her acolyte, but was, alas for her, rebuffed.

I have already mentioned Sen’s eclectic band of friends and intimates drawn from all parts of the world. One that I must revert to is the Israeli, Michael Bruno, with whom Sen discussed “fanning the flames of division in artificially generated identity confrontations” in Palestine as much as in Pakistan (a subject that I first encountered at the Cambridge Union and has since become for me something of a political and moral obsession). “When Michael and I argued about Palestine in the 1950s,” writes Sen, “I hoped his optimism would be vindicated. It gives me no pleasure that my pessimism has been proved right”.

The “South Asians formed quite a distinct group at Cambridge”, leaving behind their differences in the vivisected sub-continent and constituting themselves into a common Majlis that pre-dated Independence and Partition, and of which Sen was elected Treasurer (“to guard its non-existent treasures”) and then President. I continue to remain intrigued at Sen nowhere in his memoirs mentioning the Burmese economist, Hla Myint, with whom he wrote a widely read paper for, if memory serves, in the highly rated Economic Journal, every undergraduate’s Gita, Koran, Bible, Dhamma and Zend-Avesta rolled into one. The core of this group comprised the Pakistani, Mahbub-ul-Haq, who later pioneered the UN’s Human Development Index; a Sri Lankan, Lal Jayawardena, who went on to head the UN’s World Institute for Development Research at Helsinki; and Amartya himself, whose distinctions are so numerous as to make listing them also double the length of this overlong review.

Among his Indian friends were Dharma Lovraj Kumar, who loved accompanying Amartya to the theatre but walked out in 20 minutes if the play did not interest her, and the highly accomplished Devika Sreenivasan (later Jain), the toast of all Oxford, as well as Prahlad Basu and Dipankar Ghosh, Kumar Shankardass and Dipak Mazumdar at Cambridge, among many others, and, later, Dr. Manmohan Singh, who came up in 1955, and even then patiently heard the others out before quietly intervening in the discussion.

Alone among the higher echelons of Cambridge economists, Maurice Dobb (and Sraffa) encouraged Sen’ s attraction towards welfare economics, which traced its origins to Karl Marx and AC Pigou’s 1920 publication, The Economics of Welfare, although it was officially seen at Cambridge as “a non-subject”. Nicholas Kaldor also encouraged Sen “on the grounds that a certain amount of folly in one’s life was necessary for character-building”! Nevertheless, Sen decided to plunge into a discipline that was being explored contemporaneously by Kenneth Arrow and Robert Solow and the philosopher, John Rawls, at the other Cambridge and at Cambridge itself by the brilliant South African economist, Johannes Villiers de Graaff.

Jadhavpur and Delhi School of Economics

Finding he had completed his doctoral thesis in one year while Cambridge regulations required three years of relentless slogging before he could present his thesis, Sen, with Sraffa backing him, returned to Calcutta on the excuse of gathering material for his thesis. He was offered the post of Head of Department for Economics at the fledgling University of Jadavpur, a suburb of Calcutta, at the absurdly young age of 23. One of his colleagues, Ranajit Guha, the founder of Subaltern Studies in India, ran into him, saying, “You are very famous. I have been constantly hearing about your shortcomings and about the mistake made by the university in appointing you. So, let’s get together straight away—in fact let’s have dinner tonight.” It was the commencement of a most enjoyable and fruitful interlude in Sen’s academic life, marked by a return to the bookshops on College Street and the Coffee House.

Sen returned to Cambridge to rich accolades for his thesis, including being appointed by Trinity as a Prize Fellow. His thesis, ponderously titled Choice of Capital Intensity in Development Planning was published by Blackwell under the far more attractive title of The Choice of Techniques. His interest in his branch of welfare economics remained undiminished and he received much encouragement from two of his students, James Mirrlees and Stephen Marglin, who went on to academic acclaim in their own right.

In 1960-61, Amartya and Nabaneeta spent a year in the US, he at MIT and her immersing herself in comparative literature at Harvard. At the Centre for International Research, where Sen simultaneously held a research fellowship, he had the congenial company of two renowned development economists, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan and Max Milliken, and a host of economists, led by James S. Buchanan, were willing to give ear to his interest in social choice theory and collective choice versus individual freedom: Kotaro Suzumura, the great Japanese social choice theorist; Paul Baran, the Marxian economist; the philosopher John Rawls, and, of course, Kenneth Arrow. He also frequently exchanged views with Paul Samuelson, who “remained entirely focused on the truth that could emerge from the argument, rather than being concerned with winning the debate”—a refreshing change from the older Cambridge where argument was like a gladiatorial contest between rival strongly held ideological fortifications. The icing on the cake was that his old College Street friend and companion, Sukhamoy Chakravarty, was also in residence on a visiting fellowship.

On returning to Cambridge, UK in the autumn of 1961, he began teaching game theory. As the junior most Lecturer and Staff Fellow (perhaps as well as to discourage undergraduates from listening to such heresy) Sen’s classes were scheduled at 9am on freezing autumnal mornings. Yet, the hall was bursting to capacity. I particularly remember the awe with which I and my fellow-undergraduates heard him out on “The Prisoner’s Dilemma”, that is, the optimal choice between not knowing whether both the other prisoners would plead innocent in which case the third would be best advised to also plead innocent and they would all be released; or whether both the others might plead guilty in which case his own plea of innocence would fetch him the harsher punishment; or plead guilty when the other two are pleading innocent, getting all of them into trouble. I do not remember what the optimum choice was but do remember the thrill of excitement that pervaded the class!

He himself was by then deeply into the Apostles, a club of “the small intellectual aristocracy of Cambridge” as it was described, started in the early 19th century with a maximum of 12 elected Members who, in turn, wrote stimulating papers in their respective disciplines and were subjected to searching questions from the other Apostles present or even from “Angels”, that is, former members who had “grown wings” and were typically no longer resident in Cambridge. The proceedings were strictly confidential, leading to much speculation as to whether they were in fact a secret spying outfit, especially when the Cambridge Spies scandal broke, centred on two Apostles, Guy Burgess and Antony Blunt.

In June 1963, just as the Profumo/Christine Keeler rumpus was breaking (and just before Kim Philby, another Trinity spy defected to the Soviets) the Sens (and I separately) “packed our bags and left for Delhi”, he via his friends in Pakistan (Auden’s line, “Each sequestered in its hate” humming in his mind) to a new assignment at the Delhi School of Economics, and I to defend myself against the wholly false IB charge of being a dangerous Marxist spy working for the Soviet Union or China (it was never made clear which). I was eventually exonerated of all charges and inducted into the Indian Foreign Service. However, Chandrashekhar Dasgupta, my friend from St. Stephen’s, held that the authorities were convinced that I was indeed a Marxist—but of the Groucho variety!

Sen settled into the Delhi School of Economics. To begin with, it was like College Street, Calcutta and the India Coffee House transferred to Delhi University, for Sukhamoy Chakravarty and Mrinal Datta-Chaudhuri joined him, and their ceaseless discussions continued. Later, Dr. Manmohan Singh returned with academic honours from both Cambridge and Oxford. I remember meeting them with my IFS gang at Volga restaurant when they had gathered there in the summer of 1964 for a convivial Sunday lunch. But that moment of glory for DSE did not last. The brain-drain took Amartya and Mrinal on its swift currents back to the enticing West; Sukhamoy moved to the Planning Commission, with its radiating lanes into the corridors of power (we worked closely together on economic relief for Bangladesh in the immediate aftermath of the Liberation war); and Manmohan, of course, became PM of India!

The book ends rather abruptly at this point with the reader thinking, “Yeh dil maange more”. Amartya is only 32. He could, and should, have gone on for the 66 more years that have passed since he entered the portals of DSE. Meanwhile, my humble thanks to him for this illuminating fragment of his life.

There is a moral in all this to which he comes in his penultimate chapter, Persuasion and Cooperation. Beginning with Gurudev and ending with the sixth century Japanese Prince Shotoku, while navigating past John Stuart Mill and Walter Bagehot, and John Maynard Keynes, Sen leaves us to meditate on four gems of wisdom in statesmanship:

- “I cannot help contrasting the two systems of government, one based on co-operation (in Britain), the other based on exploitation (in colonial India)” Tagore, 1941, Crisis in Civilization

- “Government by discussion” – John Stuart Mill and Walter Bagehot

- Essays in Persuasion, 1931 – John Maynard Keynes, the title says it all

- Decisions on important matters should not be made by one person alone. They should be discussed with many” – Prince Shōtoku, Constitution of Seventeen Articles, 604 AD

Amartya Sen’s own conclusion: “Discussion and persuasion are just as much a part of social choice as voting”. Are you listening, Modiji and Amitji?