A Thugee Life

Right at the end of the book, after an epilogue and a glossary, there is a page dedicated to Publisher Credits, with an asterisk that then dissolves into a quiet line at the bottom: ‘At author’s request’. To me, after that heady deep-dive into the early days of the British Empire in India, and that hunt for one of India’s most notorious gangs of stranglers—the Phansigars—this felt like a reflection of what I had just experienced—that there are many players in a story held within the almost inconspicuous but lightly made fist of the author. In Twilight in a Knotted World, Siddhartha Sarma’s voice is somehow at the centre, the echoes rippling out into the many threads he holds.

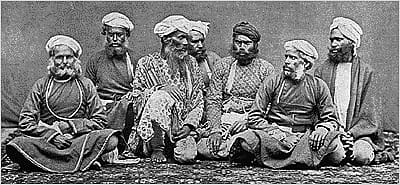

The first chapter puts us right in the heart of the action—we see the elaborate ruse used by the Phansigars in deceiving their victims before leading them to their deaths—quickly contrasted by Sleeman, assistant to the governor-general’s agent and administrative head of the Jabalpur district, involved in the discovery of rare bones in their area. The sedate environment of dry fossils and science becomes the perfect foil to the colour and reality of life on the street, of setting the tone for two very different worlds—one that watches the action from the outside while trying to solve the trail of murders and one living the life of deceit and despair. It’s a brilliant juxtaposition of a writer’s and reader’s position too, the exploration of distant worlds breathing out through immediate words.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

As Sleeman and his crew close in on the Phansigars’ trail that leads to a cinematic climax, the British too are deepening their hold in the country, looking at abolishing laws and creating a more uniform language of governance, and even though it seems like both are moving in different trajectories, they still impact each other. One of the moments in the book, when the practice of sati is abolished and Sleeman is forced to allow it in one instance, it becomes clear that every single decision made inside closed doors leads to dissonance and a reversal of reality that even in its apparent collective sameness hides a multitude of individual experiences. Even Sleeman’s own acute sense of the Indian way of living can either submit to authority or submit to reality but never overcome either.

It is interesting then that Sarma uses the third person to tell this story because while it always gives us an overview of the big picture, it only offers us glimpses of the fictional lives he creates, ensuring that no single thread becomes central. Instead, it is a tapestry of rich colours, each one deeply researched and deeply felt, and when looked at together leaves you not with the neatness of completion but with the promise of an endless unfolding.

The only part that did not work for me was the introduction of the boy found in the jungle—a version of Mowgli, so to speak—that Sleeman and his wife end up adopting as their own. While I could see the academic relevance of this boy who is said to have grown up with a wolf pack, and the idea of what it means to be human, and the dichotomy that exists in the word ‘civilised’, and the importance of language, or how we define it, it still felt uneven—and maybe unnecessary—in an otherwise tightly crafted narrative.

And yet, what this book left me with was a deep sense of melancholy for a time I did not know, and a reverence for this nuanced and layered piece of history that Sarma offers with such tenderness.