A Search for Moorings

AMONG THE WORKS of literary fiction published in this century, narratives that focus on ethical dilemmas and their wide ramifications are relatively rare. To love and death, the two eternal themes of literature, we seem to have added dystopia and this irredeemable inferno of the present, an inferno where ethical failure appears to be a settled fact. Yet, the need for forging a code of ethics as a guide to individual and collective action has never been more urgent and critical.

That said, over the past 150 years, the human search for ethical moorings in a world of rapid change did result in a rich corpus of literary fiction, especially from Europe and America. Writing from a Christian tradition, the Russian Masters were pioneers in this genre. Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov remain a perennial source of reflection on the ethics of being human. In their work during the 1940s and ’50s, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus examined the ethical dilemmas plaguing the individual in an era of great political uncertainty and large-scale violence. From the 1950s on, Saul Bellow concerned himself throughout his career of over four decades with the moral and ethical predicaments of living, albeit as a privileged Jewish intellectual, in an American society given over completely to the mercenary creed.

India, too, has produced modernist fiction that deals with individual and collective ethics. However, these have either been parables of individual morality, or contemporised versions of tales from our epics, or realist narratives in which the average individual is always vanquished by the system. While the artistic value of such stories cannot be denied, they tell us little about the wider possibilities for ethical conduct available to us. This situation is perhaps indicative of a precipitous decline of idealism, even as an abstraction, in the contemporary world.

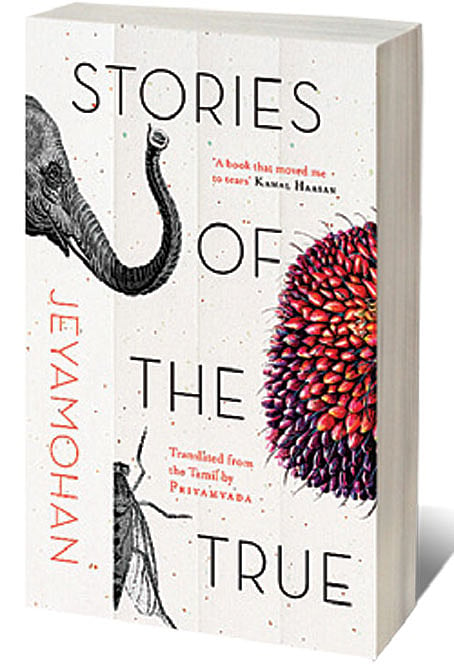

It was in response to this decline, and to examine how his “view of idealism measured against the mighty torrent of history,” that the eminent Tamil writer Jeyamohan wrote a set of stories in early 2011 that he published in a collection, Aram (available now in English translation as Stories of the True). The stories are fictionalised accounts of real people and their struggles, stories of idealism that have been put to the test of lived life. As the author says in his Preface to the Tamil edition, “they present the dialogue that idealism engages in with the darkness and rot that surrounds it. Idealism can radiate light on its own strength. It can stand on its own feet, without leaning on another. No opposing force, no matter how terrifying, can snuff it out.”

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

In one of his lectures, Jeyamohan says, “Though we have something called world literature, our sense of the aesthetic, and our understanding of ethics and morality, can come only from our own tradition, from the local [my paraphrase].” Accordingly, the 12 stories in this volume are set in the southern and western parts of Tamil Nadu, in locales deeply familiar to the author. They are rooted in the local ethos and draw on the artistic, cultural, and intellectual heritage of the Tamil country.

In each of these stories, the central character struggles to live up to a personal code of ethics in the face of adversity— betrayal, humiliation, crippling pain, killer epidemic and misogyny, to name a few—by drawing not only on their inner resources and allies by circumstance but also on the rich and profound legacy of humanity itself. As Priyamvada says in her Translator’s Note, “These stories are not simple expositions of virtue. Reaching far beyond the understanding of ethics as dichromatic, immutable codes of conduct, the narratives delve into deeper and more complex internal dilemmas.”

The opening story, ‘Aram—the Song of Righteousness’ describes the travails of an indigent writer who takes on and completes a publisher’s commercial project in order to fulfil his family responsibilities. He is cheated of his earnings by his publisher, a Chettiar. Faced with the imminent destruction of his family, the writer rushes to the matriarch of the publisher’s house and “sings Aram”, the tradition whereby “a wronged poet sings a song of righteousness and curses an adversary to ruin.” The matriarch orders her husband to pay up immediately and seeks the writer’s forgiveness.

After narrating the story, the writer muses, “Who says Dharma is only for those who rule? Dharma belongs at home, sir. Not for nothing is the married woman called Dharma pathni. She is the consort of Dharma, after all.”

In ‘Elephant Doctor’, we learn that ethical treatment of animals is possible only if we understand them on their own terms. The protagonist, an internationally renowned veterinary surgeon, wages an uphill battle every day to prevent the abuse of animals and rescue those victimised in their natural habitat by the heedless behaviour of newly prosperous Indian tourists.

A boy from a nomadic tribe becomes, by dint of hard work and dedication, an IAS officer, only to realise that he would never be allowed to wield any real power in a society dominated by the upper castes. He describes the experience of functioning in a milieu that is deeply prejudiced against him: “I became this nameless wild animal, caged in the middle of a city. When I mounted an incensed protest, it was forgiven as an innate lack of civility. When I fought back, it was dismissed as unrestrained greed. If, acknowledging my position, I remained silent, it was explained away as the impotence that represented my ilk and was approached with sympathy. My self-pity and loneliness were construed as psychological problems.”

‘A Hundred Armchairs’ is about this young man’s struggle to protect his mother, who refuses to give up the traditional ways of their tribe. His filial commitment threatens to blow his life apart. In the end, he sees that no amount of formal power will compensate for and heal the wounds that history had inflicted on his mother and her kind.

Each story invites the reader to contemplate our complex world in a deeper way and reminds us of the struggle we must wage to live as ethical humans. The dilemmas are all too real, not only because they are based on the lives of real people, but also because the author’s craft renders each character, landscape, situation and feeling vividly and with sensitivity.

The protagonists of these stories live at a distance from the world for a variety of reasons: poverty, caste, location, gender, disease, old age, eccentricity, occupation, faith. It is this isolation that necessitates and enables their idealism at the same time. They can see and respond to a greater truth beyond the common-sense framework of a given world. The courage to stand up as a collective for an ethical way of life could well be what can save us from the near-certainty of a climate catastrophe looming over our immediate future.

Stories of the True is outstanding as a translation as well. Priyamvada’s long and sustained engagement with the author’s work as a reader enables the translator to recreate the author’s ‘voice’ in English in a seamless manner. Her confident use of idiomatic English while evoking the tone and cultural location of the source text makes the collection a pleasure to read.

Despite Jeyamohan’s pre-eminent position in the world of Tamil letters and his prolific output over the past 30 years, Stories of the True is the first work to be published in English translation. More are reported to be in the pipeline. It would be interesting to see what the Anglophone milieu makes of this important and distinctive voice from the Tamil country.