A Reluctance to Forget

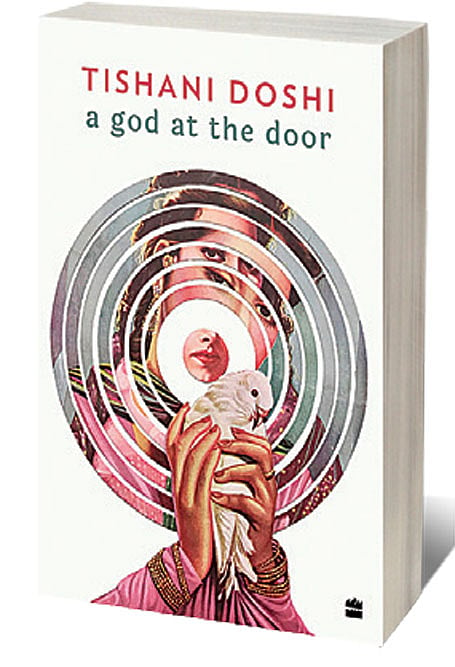

IN A GOD AT THE DOOR, well into an illustrious career in poetry, Tishani Doshi delivers a collection that prioritises craft, that favours the scalpel over the paintbrush. In this eclectic, discomfiting collection—that made it to the shortlist for the 2021 Forward Prize for Best Collection—form is chosen with clear intent. Concrete poems are cast in the shape of a menstrual cup, a uterus and a fir tree, an abecedarian tells the sweeping story of evolution as it travels through the alphabet, and stanzas alternate neatly between left and right justified to partition, juxtapose and slow down the poem. Doshi’s lines taper at a seminal word, rarely a throwaway one. Her sentences, concerned with precisely slicing through the geopolitical, social and climate events that mark our days, are contained yet rounded. She remains economical with her words, but not with the scope or the messiness of her poem. The clarity of the individual parts—form, images, turns of phrase—are often deliberately undercut by the poem’s quiet refusal to move towards resolution.

In some ways, this collection is a lament, a grieving for many of the ways in which the world fails and destroys those who are most easily displaced, most quickly silenced. The horror of the events Doshi alludes to lingers, but there’s something stronger than numbness that her words elicit—a more microscopic understanding of the effects, a fortified reluctance to forget. There’s a certain distance from many of these calamities that privilege will afford many readers and while it seems woefully inadequate to bear witness, to cease to remember would be to erase what little is left of those who have suffered. Engaging with these poems is like opening a trapdoor, descending deep into a story and not being able to demand that the narrative make moral sense.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The poems in A God at the Door sometimes turn at the close of the poems towards hope. It’s jarring and uncomfortable till one realises it is not a comforting hope one has been confronted with, but a defiant, angry one. As she writes in a poem for the imprisoned poet and activist Varavara Rao, “What else/ can we/ do but/ resist?” The questions that most often and most loudly ask to be heard in the book are: How do we live in a country that demands obeisance when what we most need is radical change? How do we live in these bodies, newly vulnerable and threatened every day?

The themes of national and physical fallibility run parallel to one another through the course of these poems. Doshi looks at the body’s undesirable vulnerabilities with something more interesting than despair and less reductive than self-love—curiosity. She writes, “I don’t want to die unless/ it’s like looking up through/ a circle of gum trees so tall/ your neck pinches just a little/ to take in the sweep of them.” The world is eroding, she seems to say, but we can’t help wanting to live, even in the fading rooms of our final moments. We don’t want, her poems stress again and again, to be alone.

In her characteristically crisp, minimally sentimental way, Doshi reminds the reader that the climate crisis and the pandemic may be exacerbating problems at an alarming rate, but the world has been inhospitable for many people for a very long time. She cautions, “Do not believe those who say it was/ wonderful before the war. Listen instead / to those saying, Get out, get out while you can.” In these times, a collection that tangoes with reality in this manner may seem like an avoidable reading companion. But perhaps, these poems are a place to channel our rage, process our personal tragedies, and remember our collective imprisoned and dead. Perhaps, this is one of the ways in which we come to accept that “the world [is] asking to be made again.”